By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Although a favorite with sports writers and fans during his salad days with the Spokane Indians and Seattle Rainiers, Levi McCormack’s sudden death Sept. 4, 1974 received barely a blurb in Pacific Northwest newspapers – four paragraphs in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, three in The Seattle Times. The Spokesman-Review carried a slightly more extensive account of McCormack’s passing at 61, but nothing that added much detail or color to his life, which had plenty.

McCormack was a tall, broad-shouldered member of the Nez Perce tribe who, at Washington State College played football under Babe Hollingberry, basketball for Jack Friel and baseball for Buck Bailey, state coaching legends all. Graduating in 1936, he caught on with the Seattle Indians and remained with them for a year after they became the Rainiers in 1938.

In the new Sicks’ Stadium, constructed that year, McCormack had to battle for an outfield job with two established regulars in Mike Hunt and Bill Lawrence as well as promising newcomer Edo Vanni, who had relinquished his job as placekicker for the Washington Huskies to join the Rainiers.

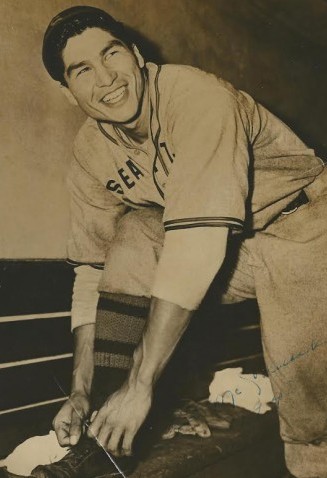

Sports writers, of course, quickly pinned the nickname “Chief” on McCormack and it fit, not only because of McCormack’s own imposing appearance (he stood 6-foot-1 and weighed 186 pounds) but because his father actually was a chief in the Nez Perce tribe. The Nez Perce fought alongside Chief Joseph in the War of 1877, a conflict in which bands of the tribe battled the U.S. Army that sought to forcibly remove the Nez Perce from their ancestral lands.

McCormack starred in football at Washington State – he caught a touchdown pass for the Cougars in their 1935 game at USC in Los Angeles – and later played semipro football in the baseball offseason. He proved good enough in basketball during his time with the Rainiers that he earned a spot on Emil Sick’s Select All-Stars when they hosted the Harlem Globetrotters in a series of Northwest exhibitions that were far more serious than comedic.

McCormack batted .308 during eight seasons in the Pacific Coast League and Western International League and might have had an opportunity to play in the major leagues except for the two developments that changed everything: Pearl Harbor and subsequent World War II service cost McCormack four years in the prime of his career, and a deadly bus accident in 1946 that Wayback Machine detailed recently in “Luckiest Man In Baseball.” McCormack survived the first but never entirely recovered from the latter.

Levi McCormack grew up near the Nez Perce reservation in the Idaho panhandle and became a star athlete of Lapwai High School near Lewiston, where he participated in football, basketball, baseball and track and field. He played freshman basketball at Washington State, football as a non-letterman in 1934 and as a letterman in 1935, the year he scored on a touchdown pass from All-American Ed Goddard against the Trojans at the LA Coliseum.

By the time McCormack left school to begin a career in professional baseball, he was the most prominent Native American to represent the Cougars athletically since the legendary William Henry “Lone Star” Dietz. Supposedly a Sioux, Dietz coached the 1915-17 football team and had his apex moment in 1916 when he took the Cougars to the Rose Bowl.

In the case of Lone Star, we say “supposedly” because, a half-century after his death, it seems that no one has decisively pinned down his heritage. Dietz claimed to have been born on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota to an Oglala Sioux mother and German father. It’s true that Dietz played football with Jim Thorpe at the Carlisle Indian School, but many historians say Dietz was actually a German American from Wisconsin who served jail time for dodging the draft during World War I because he falsely registered as an Indian.

Whatever the case with Lone Star, McCormack was the real deal. He began his professional baseball career while still enrolled at Washington State, starting in 1933 with the Lewiston Indians of the Idaho-Washington minor league, alternating as a catcher and outfielder. After two years, McCormack’s rights were sold to the Seattle Indians of the Pacific Coast League, prompting numerous headlines such as, “The Indians Have An Indian” and “The Indians’ Indian.”

One of the first mentions of McCormack in the Seattle press occurred July 26, 1936, when The Times contained the following description:

“Levi McCormack . . . that’s an unusual name for an Indian. Just think of it in the same breath with the great Indians of baseball history . . . Jim Thorpe, Moses Yellowhorse, Chief Bender, Chief Myers, Louis Sockalexis, and the rest. But the 20-year-old Indian, who deserted his native campfires to join the Seattle Indians of the Pacific Coast League, has a chance of going places in the game that has replaced hunting buffaloes, the great sport of his forefathers, as America’s national pastime.”

“He has a chance,” said manager Dutch Ruether after getting his first good look at McCormack. “He’s strong and courageous and hits the ball well. If he learns to play the outfield, he has a chance.“

McCormack hit .348 in 30 games with Bald Bill Klepper’s 1936 Indians and batted .288 in 1937 for Klepper’s nearly bankrupt ball club. McCormack had perhaps his best day in a Seattle uniform Aug. 8 that year when he collected five consecutive hits, including a home run, against the Mission Reds.

(During his time in Seattle, McCormack spent his baseball offseasons playing for the Enumclaw Silver Barons in the Northwest Football League. He caught a TD pass in Enumclaw’s 6-3 win over the Tacoma Red Devils Nov. 6, 1936.)

At the end of 1937 season, the financially squeezed Klepper sold the Indians to Emil Sick, who embarked upon a complete re-make of the franchise. In addition to constructing Sicks’ Stadium in the Rainier Valley, Sick re-branded the club as the Rainiers and made two significant additions to the roster, 19-year-old pitcher Fred Hutchinson and outfielder Vanni.

Vanni’s addition to an outfield that already included Hunt and Lawrence gouged into McCormack’s playing time. He spent one of the great seasons in Seattle baseball history alternating in right field with Vanni, hitting .294 to Vanni’s .300.

Since Vanni had been signed to great expense and fanfare (he received 4,000 shares of Rainier Brewery stock as a signing bonus), manager Jack Lelivelt made a decision entering the 1939 season to send McCormack to the Western International League’s Spokane Hawks and retain the services of the veteran Hunt.

Lelivelt wanted McCormack to play regularly, but that effectively ended McCormack’s association with the Seattle franchise and launched his career in Spokane, where he had his greatest success.

Various Spokane franchises have featured individuals of higher profile than McCormack. During the club’s 14-year association with the Dodgers beginning in the late 1950s, Los Angeles pushed through the Lilac City dozens of future major leaguers, including Hoyt Wilhelm, Don Sutton, Tommy Davis, Maury Wills, Willie Davis, Frank Howard, Ron Fairly, Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Ron Cey and Charlie Hough. Both Duke Snider and Tommy Lasorda managed Spokane club while Wills played for the Rainiers (1957) and Davis for the Seattle Pilots (1969).

Long before that, George Kelly began his Hall of Fame career with Spokane (1914). Ruether, Stan Coveleski and Earl Sheely, a future Rainiers general manager, also passed through town. But none rivaled McCormack’s celebrity. He was voted the team’s all-time popular player several times.

Spokane fans loved they way McCormack hustled on every play, sprinted to his position in the outfield, signed autographs before and after games, engaged in practical jokes and made the most of his Native American heritage. McCormack often posed for photographs in Indian headdress and performed “war dances” on command. He also delivered on the diamond for two of Spokane’s better pre-World War II teams.

In 1940, Spokane signed legendary but supposedly fading PCL slugger Smead Jolley, who had been cut loose by Oakland. The 38-year-old, slow afoot and not much help defensively, won the league batting title with a .373 average and drove in 181 runs, astonishing even by inflated PCL standards. All eight of Spokane’s regulars batted above .300, including McCormack, who hit .327 with 108 RBIs and 130 runs scored.

The Indians finished 6½ games ahead of Yakima during the regular season, but lost to Tacoma in the final round of the playoffs.

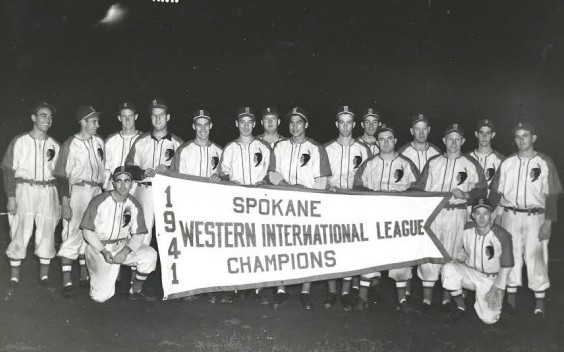

With McCormack stationed primarily in left, the 1941 Indians finished 89-44 and 18½ games ahead of the rest of the league. So dominant were they that the Western International League invoked the equivalent of a mercy rule and canceled the playoffs. McCormack hit .338 with a .485 on-base percentage and led the league with 191 hits. McCormack made the All-Star team, his last burst of glory.

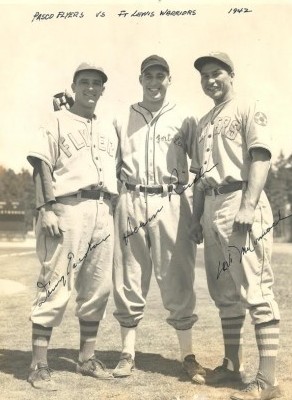

McCormack spent the next four years in the Navy, enlisting, along with Vanni, at the Federal Building in Seattle before reporting to the Sand Point Naval Station. McCormack eventually served nine months in the South Pacific and then was posted to Pasco, where he worked in aviation ordnance, instructing cadets in aircraft gunnery.

McCormack played service baseball with the Pasco Flyers along with Vanni, Mike Budnick (a teammate in both Seattle and Spokane) and Ray Ortieg (played with Vancouver) and football for the Pasco Flyers along with former Pacific Lutheran Little All-America fullback Marv Harshman (McCormack scored two touchdowns in a 33-7 win over Whitman College Nov. 21, 1942).

After the war, the 31-year-old McCormack returned to Spokane and was on his way to another good season (.316 with three home runs in 58 games) when, along with 14 teammates, he boarded a Washington Motor Coach June 24, 1946 for a cross-state trip to Bremerton for a seven-game series with the hometown Bluejackets.

Four miles west of Snoqualmie Pass, an east-bound black sedan careened across the centerline, sideswiped the bus, and sent it tumbling 350 feet down a ravine.

The bus caught fire and burned to its frame. Eight players died, five at the scene, three more over a period of days, but McCormick survived, although with a number of serious injuries, particularly one to his hip.

“I saw the headlights coming toward us on the wrong side of the road,” McCormick recalled years later for The Spokesman-Review. “The road was slippery. Our driver applied his brakes. We swerved across the road into the guardrail. We went through. We went down. I’ve never heard such hell. I don’t know why we didn’t smash the other driver. It might have been better.”

“He wore scars from the wreck the rest of his life,” Vanni told The Seattle Times following McCormack’s death in 1974. “But the scars inside were deeper. He never got over the shock and frustration of lying there helpless, watching the flames consume his best friends.”

McCormack made it back with the Indians in 1947, when a hip injury he’d suffered in the bus accident limited him to 119 games and ultimately forced his retirement.

On Aug. 25, the Indians honored McCormack in a special “McCormack Night” promotion prior to a game against Tacoma. Western International League president Robert Abel presented McCormack with a plaque and Spokane mayor Arthur Meecham delivered a speech, in which he waxed about McCormack’s popularity, at one point describing him as “an idol of Spokane fans.” McCormack strutted off with $5,000 in cash and gifts.

McCormack hit .276 in his final year. When the modern-day Spokane Indians created a Rim of Honor at Avista Stadium in 2007, McCormack was one of the four individuals inducted as permanent members. Aden, Wills and Lasorda were the other three.

McCormack, who played several years of semipro ball after leaving the Indians, ran for Spokane County coroner two years after retired from baseball and won the Democratic primary, garnering 15,483 votes. After losing the general election to Republican incumbent Frank J. Glover, McCormack entered private business. Deciding that wasn’t for him, he became a Spokane mail carrier.

McCormack married and had a big family – three sons, four daughters – and died suddenly of a heart attack Sept. 4, 1974 at 61. He is interred in Lapwai, ID., the seat of government of the Nez Perce reservation.

————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

4 Comments

Great write-up and pics, fellas, and timely, too. I’ve been reading the book Dave and Mark Armour put together for the SABR convention in Seattle, and this fits in well.

Emil Sick mostly made the right moves when he bought Seattle’s PCL team and turned around its fortunes, but letting McCormack go in favor of Hunt wasn’t one of them. Mike was extremely popular in Seattle and Civic Field (where he was married at home plate) was made for power hitters like him, but those homers at Civic became long outs to left at Sick’s Stadium and he was much less productive in two years with the Rainiers before retiring after the 1939 season. Levi had several productive years remaining (WWII notwithstanding) and was better defensively than the older and slower Hunt. It worked out well for him in Spokane, but he had PCL-level ability.

Thanks for the comments. This history– the Wayback pieces and reader comments– is fun to read, good to know and important to remember, I think. Thanks

David Eskeazi and I thanks you!

Thanks, as always, for commenting. Your remarks, as always, are appreciated!