By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Sometime in the fall of 1903, Alfred Strauss filed a written complaint with the University of Washington’s Board of Control, a student oversight committee, arguing that it should compensate him “for the loss of several teeth.” According to The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Strauss, a halfback on the football team, contended that since he had lost the choppers while “fighting for his college,” the university ought to pay his dental expenses.

Strauss did not win his case, forcing him to pay for the dental work out of his own pocket. Fortunately for UW, Strauss not only never held a grudge, but became one of the most prominent alums in school history – in fact, the “Most Loyal Alumnus Ever,” according to the University of Washington School of Medicine.

A native of Hardheim, Germany, an 11-year-old Strauss sailed to New York in 1891 in the company of an uncle, who pinned a tag on the youngster’s coat that said, “Alfred A. Strauss, Colville, Wash.,” and placed him aboard a west-bound train.

Once in Colville, north of Spokane in Stevens County, Strauss learned English, worked in another uncle’s general store, and participated in sports at Colville High School. In his spare time, Strauss performed odd jobs around the offices of the town’s physicians, Drs. Peck and Harvey, who permitted Strauss to read Gray’s “Anatomy” and Osler’s “Medicine.” Even as a teenager, there was no question what Alfred Adolph Strauss would do with his life.

He enrolled at the University of Washington in the fall of 1901, eventually earning three letters in football under head coaches Jack Wright and James Knight and another in baseball. In 1903, Strauss served as a football co-captain, with quarterback William Spiedel, on a team that defeated Nevada 2-0 for the Pacific Coast Championship in front of 8,000 at the new Recreation Park (Fifth and Mercer).

Before graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1904 with a pharmaceutical-chemistry degree, Strauss organized Washington’s first marching band and sang tenor in both the choir and Glee Club. Then, with teammates Speidel and Lewis Shearer, Strauss departed Seattle to enter medical school at the University of Chicago. Since no rule then existed to prevent it, all three graduates turned out for varsity football under head coach Amos Alonzo Stagg.

Speidel made a huge contribution to UW athletic history. While playing for Stagg, Speidel came to know Stagg’s athletic trainer, Hiram Conibear, who doubled as trainer of the Chicago White Sox. Speidel grew so impressed with Conibear that he contacted UW athletic manager (director) Lorin Grinstead and jawed him into offering Conibear the job of athletic trainer, then talked Conibear into moving to Seattle.

Conibear ultimately became Washington’s first famous rowing coach, in fact the so-called “father” of the sport at the school.

Strauss eventually graduated No. 1 in his class from Chicago’s Rush Medical School, later interned at Chicago’s Michael Reese Hospital and then did graduate work at the University of Heidelberg before returning to Chicago, where he became both a prominent surgeon and one of America’s pioneers in cancer research.

As far as can be determined, Strauss’s second involvement with UW athletics began in 1923 when Washington oarsmen participated in (and won for the first time) the Intercollegiate Rowing Association regatta – the national championships – in Poughkeepsie, NY.

Both en route to the races, and on their return to Seattle, the Huskies decamped in Chicago, where Strauss entertained coach Rusty Callow’s crews.

In 1928, Paul Schwegler, a tackle of great potential from Raymond, WA., enrolled at Washington but had a sudden change of heart and transferred to Northwestern University in Evanston, IL., a Chicago suburb.

Strauss heard about Schwegler’s switch and made it his business to “re-recruit” Schwegler on behalf of the Huskies. After Strauss’s successful lobbying, Schwegler became Washington’s first two-time All-America and was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1967, the third Husky player inducted.

Strauss became one of Washington’s most significant recruiters. Over the next two decades he sent more than 150 Midwest-based players to Washington. During that time, he employed two Chicago-area high school coaches to scout prospects in Illinois, Michigan, Indiana and Ohio.

When they identified a recruit, Strauss provided the young man a train ticket and pocket money (and sometimes tuition) and sent him to Seattle on the Northern Pacific Railroad. Or, Strauss arranged for players to drive new automobiles from Detroit to Seattle for delivery to Seattle dealerships. The young men received $50 to $75.

Strauss focused much of his recruiting on Chicago’s Polish, Slavic, Jewish and Italian neighborhoods, and many of his finds were spectacular: the Markov brothers, Vic and Ted; Max Starcevich, Steve Slivinski, Ray Frankowski, Fritz Waskowitz, Dan Lazarevich, Hurley DeRoin, the Mucha brothers, Chuck and Rudy, the Wiatrak brothers, Paul and John, and Abe Shper, the 1935 Guy Flaherty medal winner. The most prominent of the players, based on the years they won letters:

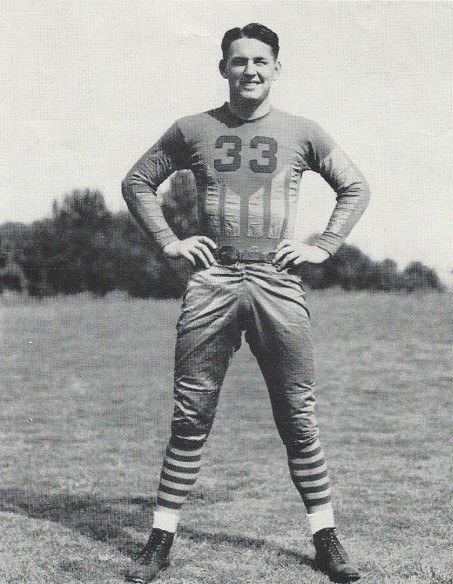

Paul Schwegler (1929-31): During his time at Washington, Stanford’s Pop Warner ranked Schwegler among the four best tackles in the country along with Wes Fesler of Ohio State, Glenn “Turk” Edwards of Washington State and Jack Riley of Northwestern.

After his final season, Schwegler represented Washington in the East-West Shrine Classic and was named Defensive Player of the Game.

Born to immigrant parents from Germany and Poland, Schwegler parlayed his football ability into a Hollywood acting career, first playing minor parts in football films and later in other genres. He played opposite James Dunne and Alice Faye as the drama film 365 Nights in Hollywood (1934) and in Bright Eyes with Shirley Temple (1934).

Schwegler, who died Dec. 7, 1980 in Newport Beach, CA., was among 11 players named to the All-Time Husky Football Team for the first 50 years of the 20thCentury. He entered the Husky Hall of Fame in 1983.

Max Starcevich (1934-36): Born Oct. 19, 1911, Starcevich grew up in a Croatian family in Duluth, MN., and went to work in a steel mill in Gary, IN. for two years following his graduation from high school. He would not have had any college prospects if Alfred Strauss hadn’t become aware of him. Strauss gave Starcevich a train ticket, pocket money and tuition and sent him to Seattle to play for Jimmy Phelan.

A fullback and guard, Starcevich made All-Coast in 1935-36, All-America in 1936, when the Huskies qualified for the Rose Bowl, and played in the 1937 College All-Star game in Chicago against the Green Bay Packers. Starcevich’s team became the first to defeat the defending professional champion, downing the Packers 6-0.

Although selected in the third round of the 1937 NFL draft by the Brooklyn Dodgers, Starcevich opted not to play professional football due to the poor wages of the day. Instead, Starcevich spent 36 years in the Seattle school system as a teacher, coach and high school principal. He also officiated football and basketball for 20 years.

Starcevich made the Husky Hall of Fame in 1989 and was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1990. He died Aug. 9 that year in Silverdale, WA.

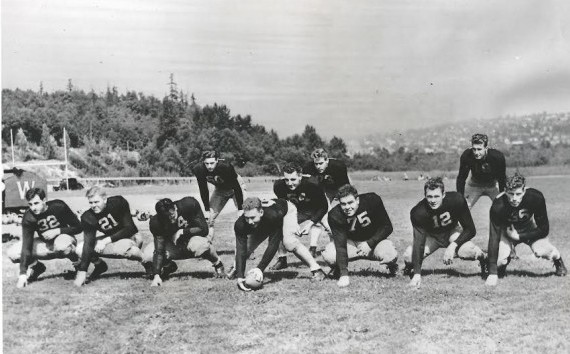

Vic Markov, 1937-39: Born in Chicago to Croatian immigrants, Markov followed his brother Ted to Washington. He starred as an offensive and defensive tackle and graduated having earned nine varsity letters in football, wrestling (heavyweight) and track and field (shot and discus).

Markov made honorable mention All-America in 1936, when the Huskies earned their first Rose Bowl appearance since 1925, and first-team All-America in 1937, when the Huskies played in the Pineapple Bowl in Hawaii.

Markov played in the 1938 Chicago Tribune All-Star game, captaining a College All-Star team that defeated the Washington Redskins, and then for the Cleveland Rams before joining the Army. During World War II, Markov landed at Normandy as a company commander with Gen. George Patton’s Third Army. He earned the Bronze Star, Purple Heart and five battle stars while fighting in the Battles of the Bulge and the Ardennes. He also took part in the D-Day invasion.

Armed with his UW business-administration degree, Markov operated the profitable Vic Markov Tire Co. on East Marginal Way South for many years. He sold out to Goodyear in the mid-1970s.

Markov entered the College Football Hall of Fame in 1976, the second Strauss recruit (following Schwegler) to do so. In 1980, he made the Husky Hall of Fame and in 1990 was a unanimous choice as a lineman on UW’s Centennial Team. Markov died Dec. 7, 1998 at 82.

Rudy Mucha (1938-40): A native of Chicago (born July 22, 1918), Mucha became a unanimous All-America center in 1940 with first-team selections by the All-America Board, Collier’s Magazine, United Press, Newsweek, Liberty and The Sporting News. He represented Washington in the 1941 East-West Shrine and Chicago Tribune All-Star games and was the No. 1 pick (fourth overall) of the Cleveland Rams that year.

Mucha played for the Rams in 1941 under head coach Dutch Clark, served four years in the Navy during World War II, and rejoined the Rams in 1945 on a team that included All-Pro quarterback Bob Waterfield. Mucha concluded his career with the Sid Luckman-led Chicago Bears, that year’s NFL champions.

Mucha, a 1990 inductee into the Husky Hall of Fame, died Sept. 7, 1982 in Blue Island, IL., at 64.

Jay MacDowell (1938-40): Born Sept. 19, 1919 in Oak Park, IL., MacDowell graduated from the town’s only high school in 1937 and arrived on the Washington campus a year later. He twice made All-Coast playing under head coach Jimmy Phelan, earned first-team All-America honors from the Newspaper Enterprise Association in 1940, and represented Washington in the 1941 East-West Shrine Game.

Selected by the Cleveland Rams in the third round (19th overall) of the 1941 NFL draft, the tackle-defensive end’s entrance into pro football was delayed by World War II. He entered the Army Air Corps as a first lieutenant and was at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked Dec. 7, 1941.

After the war, he did postgraduate work at Michigan State University for a year before hooking on with the Philadelphia Eagles. MacDowell spent six seasons in Philly, playing defensive end on championship teams in 1948 and 1949.

“My biggest memory of being with the Eagles was the lousy money we made,” MacDowell told the Philadelphia Daily News in 1991. “For the three championship games we were in, we made a total of $3,300.”

MacDowell, inducted into the Husky Hall of Fame in 1991, became a certified life insurance underwriter for Rankers Life Co., in Lincoln, NB. He died in Springfield, DE., in 1992 at 72.

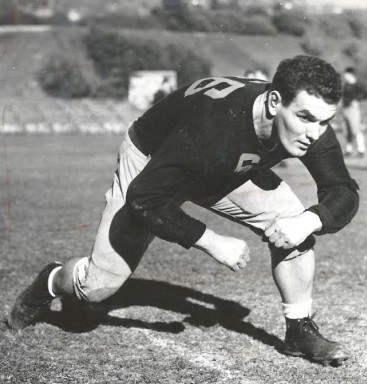

Ray Frankowski (1939-41): Born Sept. 14,1919 in Chicago, Frankowski became a consensus All-America guard in 1940-41, only part of the athletic success he had at Washington. In addition to earning three letters in football, Frankowski lettered twice as a wrestler and won the Pacific Coast Northern Division heavyweight title in 1940. In 1941, he earned a sixth letter as a member of the Washington fencing team.

Frankowski played in the 1942 East-West Shrine Classic and Chicago Tribune All-Star Game before the Green Bay Packers selected him in the third round of the 1942 NFL draft. After World War II, Frankowski played for the Packers in 1945 and the Los Angeles Dons from 1946-48. In Frankowski’s last year with the Dons, he played under Jimmy Phelan, his coach at Washington.

Frankowski, who died Nov. 27, 2001 in Laguna Niguel, CA., entered the Husky Hall of Fame in 1986 as both a football player and wrestler.

Fritz Waskowitz was another notable Strauss recruit. A Chicago native, Waskowitz earned letters in 1936 and 1937 and quarterbacked and captained the Huskies as a senior. Severely burned during the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941, Waskowitz, a fighter pilot, was shot down and killed in the South Pacific Sept. 29, 1942, the first outstanding Husky athlete to die in World War II.

In addition to recruiting three future College Football Hall of Fame players (Schwegler, Markov, Starcevich), Strauss recruited Phelan, who coached the Huskies from 1930-41 and entered the College Football Hall of Fame in 1973.

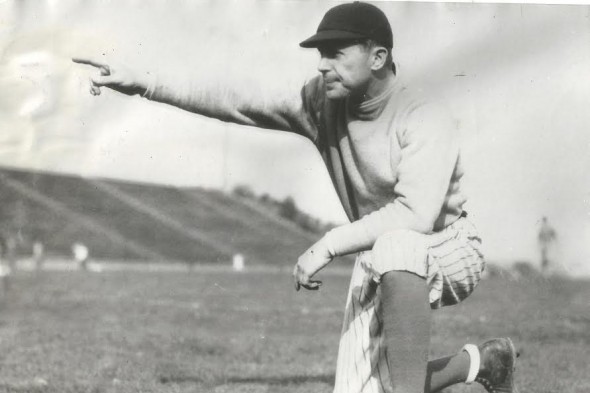

After Enoch Bagshaw (1920-29) was let go by Washington after a 2-6-1 flop in 1929, Phelan received a call from Strauss, who asked Phelan if he would be interested in the Washington job. Phelan expressed interest, Strauss made some calls, and Phelan, then the head coach at Purdue, got the job.

Phelan brought with him an assistant coach named Ralph “Pest” Welch, who succeeded Phelan in 1942. So Strauss actually had a hand in providing Washington with two head coaches.

A patron saint for generations of Huskies, Strauss attended every Washington game, home and away, for 70 years until his death in 1971 in Palm Springs, CA., at 90.

—————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com