By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

No football player in the early part of the 20th century captured the public’s imagination more than Illinois halfback Red Grange, whom Chicago American sports writer Warren Brown christened “The Galloping Ghost.” So great – and hyped — was Grange that even the best players of the era, including several hatched beneath Notre Dame’s Golden Dome (George Gipp and the Four Horseman) paled by comparison.

Grange helped dedicate Illinois’ new stadium in 1924 with a mythic performance against Michigan – 402 yards rushing and touchdown runs of 96, 67, 55 and 45 yards in the first four minutes of the contest – that not only legitimized college football throughout America’s heartland, but transformed Grange into the most popular player in America.

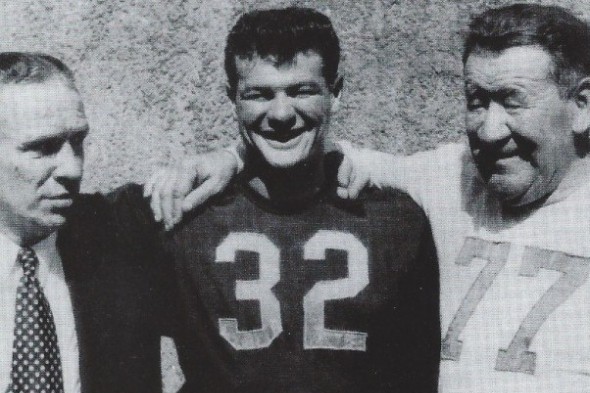

By 1925, Grange had become a three-time All-America, and within hours of stripping off his famous No. 77 jersey for the final time, he signed a professional contract with the Chicago Bears that guaranteed him $100,000 at a time when professionals routinely made $100 per game. Largely through his cut of gate receipts, Grange became a millionaire within three years.

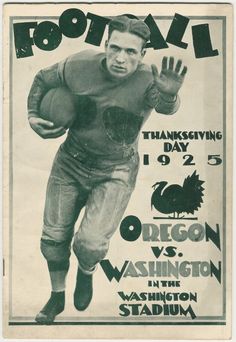

The University of Washington’s George Wilson (1923-25) might have rivaled Grange as a cash machine had his geography been different. Although not an open-field runner in Grange’s class, Wilson could throw, run, kick and play savage defense, a fact recognized by poet-sports scribe Grantland Rice, who named Wilson to his first-team All-America backfield in 1925 along with Grange and Stanford’s Ernie Nevers.

Unlike Grange, whose feats were witnessed and recorded in the center of the media universe, and those of Nevers, who played at a school whose athletic genealogy could be traced to Walter Camp and Pudge Heffelfinger, Wilson performed most of his football miracles on the muddy, rock-strewn quagmires of the Pacific Northwest, in a distant outpost a continent removed from the press machinery of the day. Consequently, Wilson’s fame never matched that of Grange or Nevers, even if his ability did.

Damon Runyan, a New York sports writer in the 1920s who became famous in the 1930s for his Broadway musical “Guys and Dolls,” covered the 1926 Rose Bowl in which Wilson almost personally dismantled Alabama.

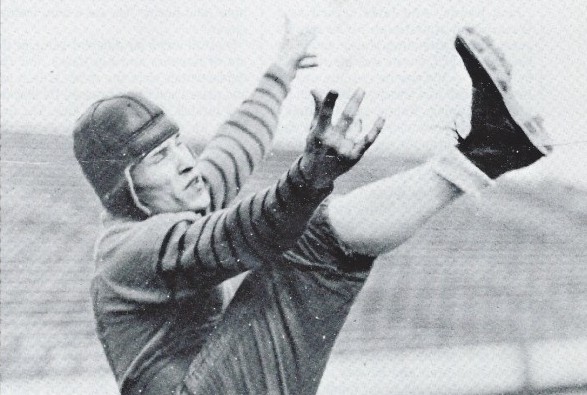

Wilson recorded an interception, set up a touchdown with a 25-yard run, produced a 36-yard run out of punt formation, threw a 20-yard touchdown pass and was in on, according to press box accounts, 10 tackles – all before halftime – as the Huskies took a 12-0 lead.

Wilson rushed for 134 rushing yards and threw two touchdown passes. Washington gained 317 yards and scored all 19 of its points with Wilson in the game. With Wilson out for 22 minutes nursing a leg injury, Washington gained 17 yards and surrendered 20 points to future movie cowboy Johnny Mack Brown’s Crimson tide.

“As Wilson went, so went Washington,” wrote The Associated Press. “The Washington All-American was all of his team’s offense, if not all of the Washington team.”

From his perch in the Rose Bowl press box, Runyon described Wilson as “one of the finest players of this or any other time,” and pronounced him a “one-man football team.”

Two weeks after receiving that Runyonesque blessing (Jan, 16, 1926), Wilson played his first professional game — he received $500 in a deal negotiated with promoter C.C. Pyle by UW sugar daddy Torchy Torrance — as a member of the Los Angeles Tigers (also known as the Pacific Coast Tigers), founded as a barnstorming team. The opponent: Grange’s Chicago Bears, who were touring the country specifically to showcase Grange to the nation.

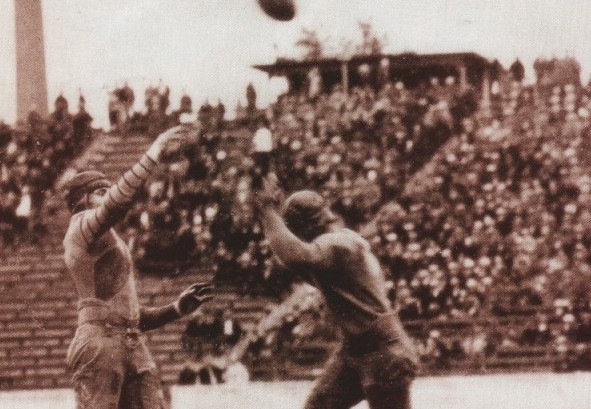

The first Grange-Wilson matchup took place in front of 75,000 at the Los Angeles Coliseum. Wilson kicked off, raced down field and slammed into Grange so hard that he nearly knocked out the Galloping Ghost. Wilson dominated the contest and out-rushed Grange 118 yards to 33, prompting Bears center George Trafton to remark, “Wilson is one tough baby to stop,” and prompting Runyon to observe, “The Galloping Ghost was clearly outshone.”

A week later, the “San Francisco Tigers,” again led by Wilson, who had 87 yards to Grange’s 41, beat Grange’s team 14-9 at Kezar Stadium in front of 23,000. Wrote a San Francisco newspaper: “Wilson plainly showed that he is a great football player, as great if not greater than Harold ‘Red’ Grange.”

In the two contests, Wilson out-rushed Grange 205 yards to 74. But by his mid-life, Wilson had become a forgotten, solitary figure laboring in anonymity on a San Francisco dock. Meantime, the Galloping Ghost became a sporting figure at the Ruth, Dempsey and Tilden level that the 1920s seemed to spawn as nonchalantly as speakeasies.

Born Sept. 6, 1901, in Everett, WA., Wilson grew up in a family of five brothers: Abe, Bonner, Phillip and Edwin, and two sisters. He first drew attention in 1919-20 when he was the best player for coach Enoch Bagshaw at Everett High, which won back-to-back national high school championships.

Wilson began his football career on Everett’s offensive line as a freshman but was soon switched to halfback. Everett’s undefeated 1919 team played Scott High of Toledo, OH., for the national high school championship. The game ended in a tie. Everett went undefeated again in 1920 and Bagshaw offered East High School of Salt Lake City $2,500 to play Everett on Thanksgiving Day in Everett.

As a warm-up, Everett beat the University of Washington freshman team 20-0, St. Martin’s College 19-0, and Long Beach High of California 28-0. Everett then took on The Dalles High School, Oregon’s high-school champions. Everett and Wilson won 90-7 to claim the Washington-Oregon interstate championship.

On Thanksgiving Day, 1920, Everett demolished Salt Lake City’s East High 67-0, after which several eastern teams challenged Everett to a national championship game. Bagshaw selected East Technical High of Cleveland and defeated the Ohioans 16-7 Jan. 1, 1921, a victory that convinced Washington to hire Bagshaw.

The Huskies didn’t so much want Bagshaw as they wanted his players, and eventually seven of them joined Bagshaw at Washington, including Wilson.

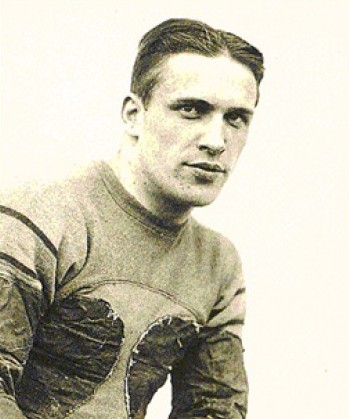

Wilson stood 5-foot-11, weighed 190 pounds and wore his hair patent-leather style, with a part down the middle, and stiffened with slickum to give him the movie-hero look that Rudolph Valentino had made the rage among campus sophisticates of the day.

With Wilson starring from 1923-25, Washington compiled a 29-2-3 record, outscored opponents 1,102-107, and appeared in the first two Rose Bowls in UW history (Navy, 1924; Alabama, 1926). Washington never again produced such staggering margins, and it must be left to speculation what Wilson might have achieved had he not been hampered by various ailments as a senior.

Newspapers of the day reported his primary malady as a “stomach ailment.” Years later, in his autobiography, “Torchy!,” Torrance clarified that Wilson suffered from a “nasty social disease,” probably contracted between Wilson’s junior and senior seasons while he worked on an Alaska fishing boat. Whatever the truth, Wilson often came out of games to toss his guts under the grandstands. But that didn’t much affect his play.

Jack Keane, who served as a Washington statistician for nearly 50 years, began attending Husky games in 1923 and Wilson mesmerized him — the way he ran, the way he threw the ball, the ferocity with which he played defense. Keane was in Husky Stadium Nov. 7, 1925, the day Pop Warner brought his great Stanford team, featuring Nevers, to town.

Seattle’s newspapers fairly bled ink over the “showdown” of All-America selections. Wilson upstaged the future Pro Football Hall of Famer not only on offense, but in concert with teammate Elmer Tesreau on defense.

The key play came on fourth down in the third quarter with Stanford, or rather Nevers, threatening to score from the Washington three-yard line.

“When Nevers came through the line,” Keane said, “Wilson and Tesreau converged on him. These two guys just demolished him, and he was through for the game. That really sticks out in my mind. Nevers was a show-off guy. But he was awfully good. Of course, we thought Wilson was better. We thought there was nobody like him.”

Keane logged five decades of Husky greats. He witnessed Chuck Carroll’s 17-touchdown season of 1928, saw Jimmy Cain come out of Oklahoma and become an All-America halfback under Jimmy Phelan in the 1950s. He saw Hugh McElhenny fly through the 1950s, Junior Coffey, George Fleming and Charlie Mitchell bash, flash and dash through the 1960s, Joe Steele romp through the 1970s and Jacque Robinson dart across the 1980s. Through all of that, Keane’s opinion of George Wilson never wavered.

“I thought he was the greatest then, and ever since I’ve carried the feeling that there has never been anybody else like him. He was a born football player.”

Football was a far different game in the era of flappers and hip flasks, but the fundamentals were the same. Wilson ran and passed and caught passes. He blocked and tackled, and he could kick. The first time he kicked in a game, he knocked the ball 55 yards. By the time he left UW, Wilson scored 38 touchdowns. To this day, no other Husky has scored more (Bishop Sankey also 38).

“He was just a bundle of guts,” said Keane. “He was so strong on offense, but he was kind of Mr. Everything. He was far and away the standout – fast and quick, and because those guys played without the kind of equipment they later developed, he got battered around a lot. But he was utterly fearless.”

Keane retained a vivid memory of the 1926 Rose Bowl against Alabama in which Wilson helped generate all of Washington’s points.

“The sports writers in California said Wilson was the greatest football player they’d ever seen,” said Keane. “It’s a crime he came along when he did. He’d have been miraculous in pro football. He’d have made a billion.”

From a financial perspective, football wasn’t much of a career for anyone in those days except for the likes of Grange and Nevers, both of whom came from marquee collegiate programs. So Wilson didn’t have much to look forward to after he set sail as a professional with the Los Angeles Tigers, a team some newspapers referred to as “Wilson’s Wildcats,” named in his honor.

The original American Football League, which came into existence largely to support the “Red Grange tour of America,” as one newspaper described, lasted just one year, after which Wilson moved to the NFL’s Providence Steam Roller, based out of Providence, RI., and a team that had been established in 1916 by members of the newspaper, The Providence Journal.

It was in Providence that Wilson crossed paths with Gus Sonneberg, a halfback who had led Dartmouth to a 28-7 victory over Washington in the first game played in Husky Stadium Nov. 27, 1920.

Wilson played for the Steam Roller for three years (1927-29), enjoying his most success in 1928 when he and Sonneberg led Providence to the NFL Championship (first ex-Husky to lead a team to an NFL title). The Green Bay Press Gazette and Chicago Tribune, the major selectors of the day, both named Wilson First Team All-NFL.

Sonneberg took up professional wrestling in the months before the Steam Roller won the NFL title, making his mat debut Jan. 28, 1928, at the Arcadia Ballroom in Providence. With his own innovation, the “Flying Tackle,” Sonneberg developed into a wrestling sensation, and won the world heavyweight championship June 30, defeating Ed “Strangler” Lewis at the Boston Arena.

Sonneberg determined he could make more money with his Flying Tackle than he could knocking heads as a member of the Steam Roller. After the 1929 season, he persuaded Wilson give up football in favor of wrestling and join him on a tour of Australia.

Wilson made good money, but came home broke when the Australian government would not permit him to take his earnings out of the country. Pro wrestling his quickest avenue to a payday, Wilson joined a U.S. circuit and toured for five years, using the names “The Wildcat” and “The Bone Crusher,” getting involved with what one newspaper described as “bad company.” In 1935, his wife of three years, an Everett woman named Kathreen Flyzik, divorced him.

On Feb. 7, 1936, slightly more than 10 years after his one-man show against Alabama in the Rose Bowl, Wilson emerged from obscurity and told a Seattle newspaper reporter that he had been promised, but had not been paid, $10,500 by the University of Washington for playing against the Crimson Tide.

Wilson said that he had received an offer of $3,500 per game to play three professional engagements immediately after Washington’s 1925 season ended. Consequently, he said, in a vote of the players as to whether they should accept the Rose Bowl invitation, he had gone on record as opposing it.

“Immediately after,” Wilson told the reporter, “officials of the university approached me and assured me that if I would forget the professional offer they would take care of me with an agreed sum from the gate receipts. I never got it, but I guess it was my own fault. I have learned since that I should have collected first and played later.”

UW officials, as well as Wilson’s former teammates, reacted with a mix of disbelief and outrage at Wilson’s story.

“It would nonsensical to think that any collegiate institution has or ever will enter into such an agreement as Wilson talks of,” said Darwin Meisnest, the school’s graduate manager (athletic director).

Tesreau, who had played high school ball with Wilson in Everett, said that no one had offered him a dime to play in the Rose Bowl. Tackle Clarence Dirks, later a Post-Intelligencer sports writer, wrote an open letter to Wilson published by the newspaper.

“Wire services quote you as saying that back in 1925 when we were rooting a football around in the mud for dear old Washington you were promised, but not paid, $10,500. Say, listen, do you mean to insinuate that you were flirting with that much dough and nobody knew about it? When you talked about being opposed to playing in the Rose Bowl, you didn’t say anything about the $10,500.”

Wilson’s claim also outraged high-minded Post-Intelligencer columnist Royal Brougham, who wrote, “A punch-drunk wrestler who found himself fading from the limelight babbled a fantastic tale and stabbed a knife into his Alma Mater. After five years of absorbing punishment from greasy giants with bulging muscles and peanut intellects, George Wilson dealt his college a below-the-belt wallop, which is the stock in trade of his wrestling profession.

“It shows the extremes to which a rassler will go to get publicity. The most popular athlete of his generation, he threw away his brilliant opportunities and, against the advice of his friends, became a tramp athlete.”

Nothing else came of Wilson’s bizarre tale, and eventually some people around the UW program began to pity him.

“We tried to get him back on his feet,” Torrance wrote in his autobiography, “by getting him accepted as a rigger for Cliff Moores, a Washington grad who made it big in the Texas oil fields.”

But Wilson failed to hold that job and returned to Everett, where he worked in the shipyards. He later spent time as a greeter at the Washington Athletic Club and eventually drifted to San Francisco, where he found work on the city’s docks as a cargo checker for the State Steamship Co.

Wilson had a brief moment of exultation in 1951 when he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame, but he remained pretty much a forgotten figure for the rest of his life.

“He had been the toast of the athletic world,” said Keane. “And he just went downhill from then on. But when he played, he was something else.”

Harold Patton was a sophomore in 1925 when Wilson was a senior. They started in Washington’s backfield and Patton scored one of Washington’s touchdowns in the 1926 Rose Bowl.

“George played the left half, I played the right,” said Patton. “George was a quiet man. He never talked much, never assumed anything for himself at all. He was a giant of a man. He had this terrific stiff arm, and he used it. I remember one time he knocked five men clear off their feet with it. I never really got to know him well because he was two years ahead of me, but I really admired the way he played.”

It was not until the 1960s that the Washington football program returned to the national prominence that marked Wilson’s time. But the years had hit Wilson hard. In addition to losing his wife, he had also hit the booze.

Feeling sorry for Wilson, Brougham invited Wilson to accompany him to the Washington locker room after the Huskies smashed Wisconsin 44-8 in the 1960 Rose Bowl. Brougham then asked Wilson to dictate his impressions of the game for the next day’s Post-Intelligencer. Wilson said:

“I want to tell you about the biggest thrill I got out of the whole day. My old friend Royal took me down to the dressing room after the big victory. I didn’t know the kids had ever heard of George Wilson. Believe me, it made me feel mighty good when some of the fellows I was introduced to said they had heard about my playing.

“A half dozen of these swell youngsters even asked me to sign their programs. You don’t know what a lift it gives to an old, gray-haired guy when he finds out he’s not forgotten.”

In 1969, in conjunction with the Centennial celebration of college football, Wilson was named to the All-Time, Western All-Star team. In the backfield with him were Nevers, Morley Drury of USC and O.J. Simpson.

Significantly, the backfield did not include Norm Van Brocklin, Kenny Washington, Jackie Robinson, Herman Wedemeyer, Frankie Albert and Terry Baker, the West Coast’s first Heisman Trophy winner. It also did not include Hugh McElhenny, who would enter the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, OH., one year later.

“As a player,” said Keane, “George Wilson was unparalleled in his time.”

But Wilson was ultimately cursed by geography, by a jock mentality that sabotaged his education, by the momentary lure of a few bucks, and several personal demons. If he’d come along 10 to 15 years later, when pro football was beginning to flower, Wilson might have prospered along with it. Instead, a dimming limelight ground him out.

Booze may have gotten Wilson, as Torrance suggested. But the official diagnosis was that the greatest player in Washington’s first 50 years, the player who outplayed Nevers, nearly outplayed Alabama, and separated the Galloping Ghost from his senses, died of a heart attack Dec. 27, 1963. He was alone, working on the San Francisco docks.

Later discovered among Wilson’s possessions: a train ticket to Pasadena, where he planned on watching Washington’s Jan. 1, 1964 Rose Bowl matchup with Illinois. He missed it by less than a week.

After Wilson’s death, Brougham wrote, “George Wilson was quietly buried in Everett this past week. The splendidly gifted All-American died just before the Rose Bowl game, an event in which he had distinguished himself so brilliantly as a Washington halfback 40 years ago. Another man of steel, his heart suddenly stopped ticking as he worked on the San Francisco docks.”

Along with Bob Schloredt (1958-60) and Steve Emtman (1989-91), Wilson is one of only three Huskies enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame (1951), Husky Hall of Fame (1980) and Rose Bowl Hall of Fame (1991).

He also was named to Washington’s All-Time Team in 1950, to the All-Time, All-Northwest team in 1977 and to the All-Centennial Team in 1990.

In 2005, The Everett Herald published a list of the top 50 athletes in Snohomish County history. Wilson came in at No. 5 behind Earl Averill (baseball), Rosalynn Sumners (figure skating), Chris Chandler (football) and Anne Quast Sander (golf).

—————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com

3 Comments

I’ve believed for a long time that Wilson was the best-ever Husky player–this piece reinforced that. What a football player he was.

Wilson’s jersey, number 33, is one of only three retired numbers for Husky football.

Great piece! Interesting how many good players and coaches have come out of Everett over the years.