By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Author Edgar Rice Burroughs introduced Tarzan in 1912 and began selling his “ape man” stories to film producers in 1917. By all accounts, Burroughs loathed the cinematic perversion of his signature character: From Elmo Lincoln to Johnny Weissmuller, Hollywood cast Tarzan as a monosyllabic savage in contrast to the cultured, well-educated English “Lord Greystroke” Burroughs created for his novels.

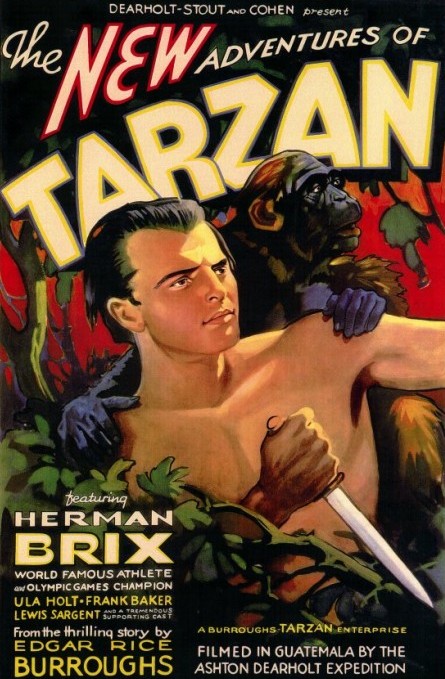

Finally, in 1934, Burroughs had an opportunity to present his version of Tarzan. That year, with three business associates, Burroughs formed “Burroughs-Tarzan Enterprises.” Urban legend has it that Burroughs personally selected the lead actor, but in fact producer Ashton Dearholt made the choice after auditioning more than 100 hopefuls.

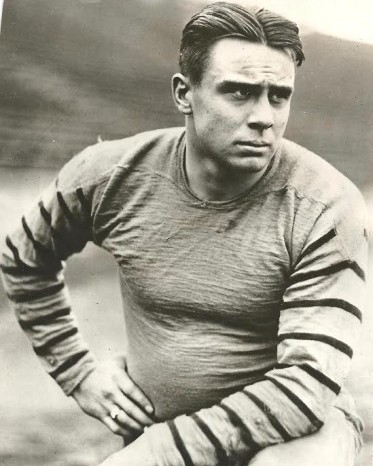

Dearholt settled on a 28-year-old, 6-foot-3, 210-pound Tacoma native who had a strong athletic background, a perfect physique, and an economics degree from the University of Washington. Within a month, Herman Brix, a former All-Coast football player under Enoch Bagshaw and world record holder in the shot put, found himself en route to the jungles of Guatamala along with a cast and crew of 29 to begin production on The New Adventures of Tarzan. In a bit of irony, they made the voyage on a steamship named Seattle.

Brix knocked around Hollywood long enough that he nearly became Tarzan in 1932 when MGM cast Tarzan The Ape Man, the first of 12 films to feature Weissmuller. But a shoulder separation Brix suffered in 1931 while filming the low-budget movie Touchdown (Brix had an uncredited cameo along with football legends Jim Thorpe and Roy Riegels) not only ensured that the part went to Weissmuller, it kept Brix off the 1932 United States Olympic team.

Born May 19, 1906, in Tacoma, Harold Herman Brix grew up in a well-to-do immigrant family from Germany (one of the first in Tacoma with indoor plumbing) that included father Anton, a lumberman who operated a couple of logging camps (Herman toiled in those camps), mother Minna, brothers Egbert and Walter and sisters Helen and Anna.

Herman competed in football, basketball, soccer, swimming, and track and field at Stadium High, and also acted in many of the school’s dramatic productions, including The Pirates of Penzance, in which he had the lead role.

“There was always a fight between the music director and the athletic coaches as to who was going to get my time after school,” Brix said in a 1970 interview with a Stadium High alumni publication.

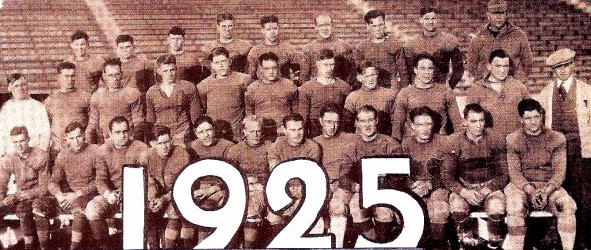

At Washington, Brix played freshman football in 1924 and in 1925 was part of one of the greatest teams in school history, a 10-1-1 club that featured five sets of brothers (Herman and Egbert Brix, Elmer and Louis Tesreau, Brick and John Mitchell, Bob and Gordon Thompson, Hugh and Walden Beckett), outscored its opponents 461-39 and suffered its only loss (20-19) to Alabama in the 1926 Rose Bowl.

Brix lettered three years, from 1925-27, and, as Washington’s left tackle, blocked for the first two consensus All-America selections in UW history, running backs George Wilson (1923-25) and Chuck Carroll (1926-28). Although an All-Coast selection, Brix made his biggest mark in track and field as a shot putter under head coach Hec Edmundson.

“All I knew about shot putting when I started out was that my brother (Egbert) could do 44 feet and I decided I wanted to beat him,” Brix told The Washington Post in 1997. “So I got a shot and went to work and made up my mind to do 45 feet.”

Brix did a whole lot better than that. He captured the NCAA title in 1927 with a throw of 46-7 3/8 and earned a spot on the 1928 Olympic team by winning the U.S. trials at 51-2.

On his first attempt in the Amsterdam Games, Brix threw a world and Olympic record 51-8, a mark that lasted all of 41 minutes, until American teammate John Kruk threw 52-0¾. The 22-year-old Brix, whose 51-8 stood as the Washington record until March 7, 1956, when Larry Pulford broke it, settled for the silver medal.

From 1928-31, Brix won four consecutive AAU outdoor shot titles and the 1930 and 1932 AAU indoor crowns. On Aug. 23, 1930, Brix was part of one of the great days in Washington track and field history.

At the AAU Championships in Pittsburgh, Steve Anderson equaled the world record in the 120 hurdles (14.4), Paul Jessup shattered the world mark in the discus (169-8¼), Eddie Genung set an American record in the 880 (1:53.4), and Brix set an American record in his event (52-5¼).

In 1932, Brix tossed a career-best 52-8¾ for his second world record, but the shoulder separation he suffered while filming Touchdown caught up with him. He missed out on a chance to compete for a gold medal at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles (a throw of 52-8¾ would have won the gold in LA).

By that time, Brix had moved from Seattle to compete for the Los Angeles Track Club. To support himself, took on a variety of odd jobs, including logger, insurance salesman and occasional Hollywood stunt man. Then, at a youth sports camp, Brix met Douglas Fairbanks Sr., the swashbuckling star of such silent classics as The Mark of Zorro (1920), Robin Hood (1922) and The Thief of Baghdad (1924).

The two became friends and, after Fairbanks persuaded Brix to give acting a try, arranged for Brix to take a screen test at Paramount. The studio liked what it saw and Brix started to receive roles immediately, appearing in 10 films between 1931-34, including Million Dollar Legs (1932 with W.C. Fields), Riptide (1934, Norma Shearer) and Treasure Island (1934, Lionel Barrymore, Jackie Cooper) before Burroughs endorsed Dearholt’s choice of Brix for the lead role in The New Adventures of Tarzan.

The picture took four months to complete and was the first Tarzan movie filmed in an actual jungle. In the course of the action, Brix fought off a lion, a jaguar and alligators. Brix performed most of the stunts, twice suffering injuries after falling from his swinging vine. During filming, a sharpshooter kept an eye peeled for poisonous snakes and guarded Brix from crocs. Those weren’t the only hazards.

The Jan. 12, 1935 New York Times carried this item: ”Tarzan, two cameramen attacked by Guatemala Indians for disturbing religious ceremonies during filming of the picture.”

“The natives were sure we were hexing the village as well as desecrating an old church in the square,” Brix explained in a 1973 interview. “They did throw stones as a warning to stay away and not point the cameras at religious objects.”

The New Adventures of Tarzan did not enjoy much success. MGM, which made Tarzan The Ape Man, had just released the sequel Tarzan and His Mate and did everything in its power to squelch the upstart film. The studio successfully strong-armed theaters from booking the Brix film, which wound up in only small independent places.

MGM also worried that Brix’s interpretation of Tarzan would become more popular than Weissmuller’s. It didn’t, although author Gabe Essoe wrote in his book, “Tarzan of the Movies,” that Brix’s portrayal marked the only time between silent films and the 1950s that Tarzan was accurately depicted on film.

“Herman Brix brought a presence to the screen that many people feel personifies the Tarzan of the books,” Danton Burroughs, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ grandson, wrote in the foreword to “Please Don’t Call Me Tarzan: The Life Story of Herman Brix/Bruce Bennett,” a 2001 book by Mike Chapman.

Brix, Burroughs wrote, “was lean and muscular, articulate and dignified. He moved with the superb athletic grace that my grandfather envisioned, and he played the role to perfection.”

Because of MGM’s politicking, The New Adventures of Tarzan languished. Ultimately, the film was serialized and re-titled Tarzan and the Green Goddess. It remained in continuous release until it was sold to television in the early 1960s.

Paid $75 per week for the movie, Brix never made another Tarzan film, and had a difficult time getting work from his primary employer at the time, Warner Bros. Brix, in fact, was set to test for a Warner Bros. picture, but it was canceled after the casting director saw a photograph of Brix as Tarzan in Life magazine.

“He said they couldn’t use me,” Brix told Chapman. “I asked why, and he said the audience would see me as Tarzan and wouldn’t accept me as an actor.”

Still, Brix rarely lacked for work. After The New Adventures of Tarzan, Brix appeared along side Bela Lugosi in Shadow of Chinatown (1936), Fighting Devil Dogs (1938) and in three dozen other nondescript films, mostly in bit parts, and sometimes in two-reeler comedies, such as The Three Stooges.

Brix consistently failed to land meaty roles because he was too identified as “Herman Brix, former Tarzan and all-around action star.” So after appearing in the Republic Pictures serial Hawk of the Wilderness (1938) as the Tarzan-like character Kioga, Brix dropped out of films for a couple of years, took acting lessons, and re-emerged to earn contracts with Columbia Pictures and Warner Bros. under the stage name Bruce Bennett.

“I realized the name Herman Brix was associated with Tarzan, so I made up a list of seven or eight names and asked people which they liked best,” Brix told Chapman. “Bruce Bennett was the name I came up with.”

Bennett received leading roles roles in World War II action films such as Atlantic Convoy (1942) and Sabotage Squad (1942) and became a dependable secondary leading man in several “women’s pictures,” such as Mildred Pierce (1945) as Joan Crawford’s ex-husband, as well as A Stolen Life (1946) with Bette Davis, Nora Prentiss (1947) with Ann Sheridan and The Man I Love (1947) with Ida Lupino.

Bennett took on his most substantial role in 1948 when Humphrey Bogart, with whom he had starred in Sahara (1943) and Dark Passage (1947), pushed for him to play the role of ill-fated gold prospector James Cody in the John Huston-directed The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Bennett beat out Ronald Reagan for the part.

“I wish I would have had more to do in the film,” Bennett told The Christian Science Monitor in 1999. “I hated to get killed so soon.”

Bennett played a series of gritty roles as an encore to The Treasure of Sierra Madre. He starred as a detective in William Castle’s Undertow (1949) and a forensic scientist in John Sturges’s Mystery Street (1950, with Ricardo Montalban).

Bennett also played an aging baseball player in Angels in the Outfield (1951, Keenan Wynn, Janet Leigh). The same year, he moved into a series of western and military roles, including Love Me Tender, a 1956 Elvis Presley film set during the Civil War.

Bennett spent much of the remainder of the 1950s and a good part of the next two decades working in television, appearing in such series as Playhouse 90 (1957), 77 Sunset Strip (1958), Perry Mason (1958-65), Whirlybirds (1959), The Virginian (1967) and Lassie (1970-71). Bennett also had starring roles in a couple of sci-fi clunkers, The Alligator People (1959) and The Fiend of Dope Island (1961), which he wrote and directed.

Brix/Bennett retired from acting in the mid-1970s and became the sales manager of a major vending machine company and a real estate investor. He worked well past his 80th birthday. Fit and still athletic, Brix/Bennett enjoyed parasailing and skydiving into his 90s, once jumping out of a plane at 10,000 feet over Lake Tahoe when he was 96.

Reclusive in his dotage, Brix/Bennett eschewed interviews, preferring to devote his private time to Jeanette, his wife of 67 years, and two children.

One of his last semi-public appearances was Dec. 30, 1999 when, at the request of Washington football coach Rick Neuheisel, Brix/Bennett spoke to the squad days before the Huskies faced Purdue in the 2000 Rose Bowl.

He lived another seven years. The 100-year-old Brix/Bennett died Feb. 24, 2007, at the Santa Monica-UCLA Medical center of complications from a broken hip.

————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com