By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Quizzical looks crossed the faces of most University of Washington football fans when they learned in January 1957 that Jim Owens had replaced Darrell Royal as head coach of the Huskies. The Oklahoma native had no national profile, had never been a head coach anywhere, and had yet to turn 30, all of which made him an incongruous choice to resurrect a program still reeling from a slush-fund scandal that brought with it a two-year probation.

Hired in the wake of NCAA penalties, UW athletic director George Briggs got wind of Owens when he tried after the 1955 season to replace head coach Johnny Cherberg, one of the scandal’s chief victims. Briggs first offered the Washington job to Duffy Daugherty of Michigan State, then to Bear Bryant of Texas A&M, and finally to Bud Wilkinson of Oklahoma.

All three turned down Briggs, but Wilkinson suggested Royal, his former assistant and head coach at Missouri State. Briggs took Wilkinson’s advice. Then, when Royal suddenly quit to take the head job at Texas after only a year on the job, he told Briggs during an exit interview that he knew someone who would “make a great coach for somebody someday.”

Briggs hired Owens Jan. 21, 1957 on a three-year deal paying Owens $15,000 per year. The new coach introduced himself with something none of his new players would forget: The Death March. Carver Gayton, a letterman from 1957-59, reflected on the “march” in an article for historylink.org:

“I was recruited to the University of Washington to play football by head coach Darrell Royal in 1956 and played freshman ball that year. In 1957, after Royal’s departure to the University of Texas, Jim Owens was hired. Owens immediately initiated a rugged and disciplined approach to training and off-campus deportment that was unprecedented in the history of Husky football. Some players hated it; others, like me, welcomed the challenge.

“At the beginning of our ’57 season during an August afternoon session, in one of our two-a-day practices, Coach Owens became very angry and disappointed in the progress of our practice that afternoon. It should be noted that the temperature was 90 degrees with a humidity level close to 90 percent.

“After an hour and a half of lackluster scrimmage, he had the team go through a series of continuous start and stop sprints that took a least another two hours. We were allowed no water during the practice. Few of us remember exactly how long it lasted.

“That practice session is now known as the infamous ‘Death March.’ By the end of the afternoon I had lost close to 15 pounds, many players fainted, at least six were taken to the hospital, and predictably, a number of them quit the team. (A very similar event, depicted in the book The Junction Boys by Jim Dent, took place at Texas A&M a few years earlier under Coach Bear Bryant where, coincidentally, Coach Owens served as an assistant.)

“Of those who participated in the Death March, I was one of the five remaining players who became members of the 1960 Rose Bowl team. That one incident was a primary contributor to the myth and legend of Jim Owens. In many ways, I believe it was a metaphor of how he approached not only football, but life. One had to “pay the price” in order to succeed.

“Years later, however, one of Coach Owens’ top assistants told me that Owens regretted how he conducted the Death March but never expressed his feelings to the players. Bear Bryant on the other hand apologized directly to team members for the Junction Boys incident at Texas A&M. Many of us who endured the ‘march’ considered our survival as a badge of courage and determination.”

Under the 29-year-old taskmaster, the 1957 Huskies got off to a slow (0-4-1) start that didn’t reverse itself until Owens unveiled an unbalanced line against Oregon State, enabling the Huskies to pull off a 19-6 win. Washington fans, without a decent team to watch since Don Heinrich (1952) graduated, were so euphoric that they poured onto the field, tried to pull down the goal posts and then ran through the ranks of the Oregon State band. Fights broke out, a bandsman fell, and two Washington students were booked into jail.

Jim Owens football arrived, but without a lot of early positive results.

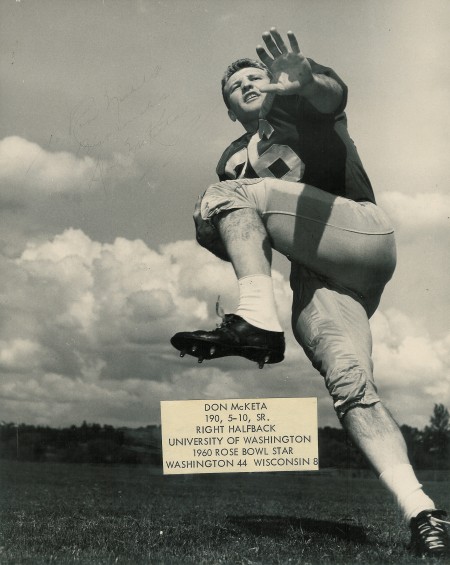

In 1958, the Huskies featured 30 sophomores, among them halfback Don McKeta, a Navy veteran; tackle Kurt Gegner, a native of Germany; Roy McKasson, a center from Tacoma; guard Bill Kinnune, an Everett product; Seattle end Lee Folkins; guard Chuck Allen from Cle Elum; RB George Fleming, a Texan who had played at East Los Angeles Junior College, and Bob Schloredt, a quarterback/defensive back from Gresham, OR.

The Huskies labored through a 3-7 season, providing scant indication that a major change was imminent, just as it was in the Pacific Coast Conference. In the wake of the 1956 slush fund scandal, as well as irregularities in the USC program, the PCC broke apart and realigned with Washington joining USC, UCLA, Stanford and California in the Athletic Association of Western Universities, or Big Five. Left out: Oregon, Oregon State, Washington State and Idaho.

UW defensive end John Meyers explained the transformation under Owens to Huskies historian Dick Rockne, a reporter for The Seattle Times.

“The coaches taught us to block with our heads. A lot of teams didn’t. They blocked with their shoulders so they wouldn’t hurt their necks or ding their noses. Hell, we blocked with our noses. We tackled with the nose. And that went right back to the philosophy that we were going to hurt people. We were going to break ribs, break noses.”

Knowing that the national perception of the West Coast style of play was that it was practically intramural ball compared to the East and Midwest, Owens went out of his way to toughen his players. The Big Ten and PCC had met 13 times in the Rose Bowl since 1949 and the PCC won once.

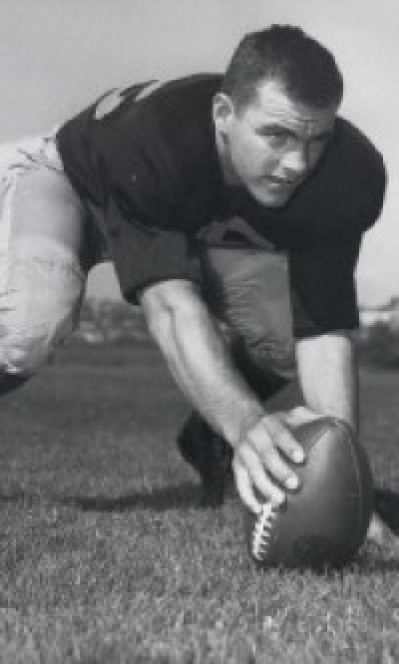

The Huskies opened 1959 with a 21-12 win at Colorado, but starting quarterback Bob Hivner suffered a broken finger, tough for him but a great turn for the Huskies. Owens elevated Schloredt, who had only 10 percent vision in one eye and didn’t dazzle with his arm or speed. But he didn’t seem to know how to lose.

The Huskies clobbered Idaho (23-0) and Utah (51-6) and and then met Stanford, a passing team — there weren’t many of those in 1959 — that had lost to Washington only once in six previous meetings. But McKeta broke a 30-yard TD run and Fleming kicked a field goal as the Huskies opened Big Five play with a 10-0 upset.

Ineligible for the Rose Bowl due to NCAA sanctions, USC slowed Washington’s momentum with a 22-15 victory at Husky Stadium, but Schloredt orchestrated a rally from a two-touchdown deficit the following week as UW defeated Oregon 13-12. Schloredt also threw a pair of touchdowns in a 23-7 win over UCLA and tossed another to McKeta as Washington edged Oregon State 13-6.

Ray Jackson then pounded for 105 as the Huskies shut out California 20-0 in a game in which Washington overcame 162 yards worth of penalties.

While the Big Five had excluded the Oregon schools, both remained eligible for the Rose Bowl for one final time. Heading into the last game of the season, the Huskies and Ducks were even in the race to Pasadena.

On rivalry weekend, the Huskies turned back Washington State 20-0 and Oregon State upset Oregon 15-7, providing Washington with its first Rose Bowl invitation since 1943 with a regular-season record of 9-1-0.

Oddsmakers installed Big Ten champion Wisconsin as a two-touchdown favorite over a Washington club that didn’t exactly exude much confidence.

“Hell, these were the big guys from the Midwest,” Meyers told Rockne. “But after we found out that they didn’t hit as hard as we thought they would, that they got out of shape in a hurry, well, we got some confidence.”

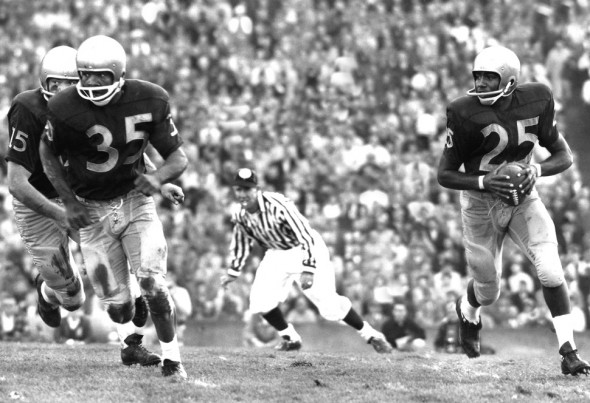

Schloredt, who started the season as the backup quarterback and finished it as an All-American, ran for 81 yards and threw for 102. Folkins made one of the great catches in Rose Bowl history for a touchdown, and Fleming returned punts 53 and 55 yards and scored 14 points on a touchdown, field goal and five PATs in a 44-8 romp. Washington finished No. 8 in the final Associated Press poll, taken in those days prior to the bowl season.

With Owens returning all of his key players in 1960, the Huskies opened the year ranked No. 3 by the AP, but ran into injuries. Schloredt suffered a broken collarbone and missed six games. Meyers, Allen, Gegner and Kinnune all missed at least two games, which could have devastated the club in an era of one-platoon football.

But the Purple Gang found a way, winning four times in nine games by five or fewer points.

The one smudge on the record – a significant one – occurred Oct. 1 when Navy arrived at Husky Stadium with star halfback Joe Bellino, who would go on to win the Heisman Trophy.

The Huskies led 14-12 with two minutes to play and Schloredt retreated to punt. But he mishandled a poor center snap and was downed on the Washington 24. Navy kicked the winning field goal with 14 seconds remaining. It would be Washington’s only defeat.

The Huskies recovered to beat Stanford 29-10. Washington then defeated UCLA 10-8, but Schloredt broke his collarbone. The following week, Washington fell behind future Heisman winner Terry Baker and Oregon State 22-15, but rallied behind two Charlie Mitchell touchdowns and won 30-29, a victory that Owens described as “the greatest comeback I ever saw.”

A week later, Oregon led UW 6-0 in the fourth quarter. With two minutes to play and Washington on the Ducks’ 47, Hivner, subbing for Schloredt, dumped the ball off to McKeta at the 37, where everyone in Husky Stadium expected him to step out of bounds to stop the clock. But McKeta suddenly turned upfield, left CB Dave Grayson looking at his heels and sped for a touchdown. Fleming’s PAT made it 7-6 and the Huskies escaped again.

USC gave Washington its only blemish a year earlier, but this time the Huskies breezed 34-0 as Fleming broke a 65-yard punt return for a touchdown and Jackson scored twice. A 27-7 cruise past Cal clinched a return trip to Pasadena with one game remaining against Washington State in Spokane.

The day of Nov. 19 was bitterly cold, made worse for the Huskies when McKeta limped into the locker room in the second quarter with a deep gash on his right calf that required 10 stitches. Washington State scored early in the fourth quarter, but Washington tied the game on Kermit Jorgenson’s two-yard plunge. Instead of going for the tie, Owens opted for two and Jorgenson found McKeta in the corner of the end zone for the winning points.

More than anyone, McKeta was the heart of the Purple Gang. He grew up in a small coal-mining town in rural Pennsylvania and was forced to quit high school and work because his family needed money. McKeta hired on with a construction company at age 15 and, a year and a half later, went to work climbing telephone poles for the Philadelphia Electric Co. Then he joined the service.

“I went through a couple of military programs,” McKeta said. “Then I turned out for football at the Memphis Training Center and all of a sudden I was the starting halfback. Then I got shipped to California.”

That’s where he met Joe Moore, under whom he played service ball for a couple of years. McKeta was good enough to draw the attention of Cleveland Browns and Philadelphia Eagles. USC, Colorado and Oregon also pursued him.

“My greatest desire,” McKeta said, “was to play for Len Casanova at Oregon.”

On Jan. 1, 1958, McKeta sat in the 77th row at the Rose Bowl watching Oregon play Ohio State, wondering what it would be like to suit up for the Ducks. Later that summer, he drove his Ford convertible to Eugene, but an offer never came. So he headed to Seattle and turned out for football at 23.

Four years later, he owned two Guy Flaherty medals, awarded to the most inspirational player each year (even Guy Flaherty didn’t win two). But the award he cherished most was 3/8-inch sparkplug that the Washington linemen gave him to symbolize what he meant to the team.

“We didn’t have an outstanding offensive player,” McKeta said of the 1958-59 Huskies. “But Bobby Schloredt took us to the first Rose Bowl when nobody expected us to go, and Bobby Hivner took us to the next Rose Bowl when everybody was gunning for us. The catalyst for us was our defense. We had an outstanding defensive team. The other teams just couldn’t get the ball in the end zone against us.” The 1958-59 Huskies outscored 22 opponents 525-180.

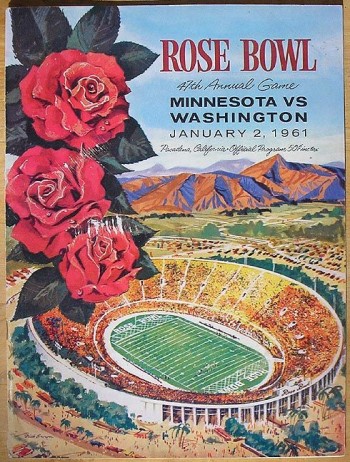

Still, by New Year’s Day, 1961, with Washington paired against Minnesota in the Rose Bowl, no one quite knew how to peg the Huskies. They had a 9-1 record, but most of their wins had been hair-raising. Schloredt hadn’t played since October and fullback Jim Jones just had his appendix removed.

As he had against Wisconsin a year earlier, Fleming set the early course, returning a punt 17 yards to set up his 44-yard field goal. Then Schloredt, playing for the first time since his injury, directed a 62-yard scoring drive that ended with his three-yard TD pass to Brent Wooten. He then took the Huskies 68 yards and scored the TD himself for a 17-0 halftime lead.

Minnesota scored once after intermission, but it was not enough as Washington concluded its second consecutive 10-1 season. Although the Huskies defeated the No.-1 ranked Golden Gophers, they finished No. 6 in the Associated Press poll, again because the final polls were taken before the Rose Bowl.

One accredited selector, the Helms Athletic Foundation, a big deal in those days, crowned its national champion after the bowl season. Helms selected the Huskies.

Although more than a half a century has passed, no series of teams is more permanently fixed in Washington football lore than the Purple Gang, Washington’s first back-to-back Rose Bowl champions (there wouldn’t be another until 1990-91).

Given that achievement, it is little wonder that the 1959-60 Huskies became the most decorated teams in Washington’s first 100 seasons. Schloredt and McKasson were both All-America choices and Schloredt probably would have been a two-time choice if injuries hadn’t cut short his senior season. Schloredt settled for becoming a two-time Rose Bowl MVP and a member of both the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame and College Football Hall of Fame. Owens, Schloredt, McKasson, Fleming and McKeta all were inducted into the Husky Hall of Fame. The entire 1959 team was inducted in 1994.

The numbers tell an impressive story – Washington ranked either No. 1 or No. 2 n the conference in scoring offense and scoring defense in both Rose Bowl seasons – but the major reason for the team’s success was that the players bought into McKeta’s phrase, “play it from the heart.”

While Schloredt, McKeta, Fleming, Jackson, Folkins and Pat Claridge and the rest of Washington’s skill players received a majority of the publicity, both teams had superb offensive and defensive lines. Schloredt won the 1960 Rose Bowl MVP award, but McKasson was the key figure as he neutralized Minnesota All-America Tom Brown.

Only one of the key operatives in the 1960 and 1961 Rose Bowl teams had a pro career worth noting. Chuck Allen, a 17th-round pick by the Los Angeles Rams in 1961, played eight years with the San Diego Chargers, two with the Pittsburgh Steelers and one with the Philadelphia Eagles.

Ben Davidson, a member of both Rose Bowl squads, played sparingly because he had not yet developed. But he went to the New York Giants in the fourth round as a 6-foot-8, 270-pound project, spent a year in Green Bay and two in Washington and then became a multiple All-Pro with the Oakland Raiders.

Owens received much of the credit for the rejuvenation of West Coast football. After Washington’s 1961 victory, West Coast schools won 13 of the next 20 Rose Bowls.

As the years went by, Owens didn’t fare as well. The Huskies played in the 1964 Rose Bowl against Illinois and didn’t win another conference title in his tenure, which ran through the 1974 season. He had three decent teams with Sonny Sixkiller at quarterback from 1970-72, but his final years were marked by such profound racial strife in the program that when a statue was unveiled in his honor in 2003, some of his former players protested bitterly before reconciliation occurred.

By then, Owens was living in Big Fork, MT., where he died June 6, 2009 at 82.

—————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

8 Comments

I enjoyed your story. I followed the Huskies through my childhood. My Mom and I had the pleasure of meeting Coach Owens and Coach Schloredt.

Those two years–’59, and ’60-were my first years of following college football. I had turned 13 the summer of ’59, and on New Year’s Day 1960 several of my friends were over to watch the Rose Bowl. It was a fairly typical Seattle January day–raining.but not all that cold. Well, except for the one guy who was the 2-years-younger brother of a friend. We decided that we’d toss him off the porch into this rather spongish (it held a LOT of water) shrub every time the Huskies scored. 44 points they scored. We were all lucky he didn’t wind up with pneumonia.

I remember that devastating loss to Navy even today. Asst Coach Tipps was my neighbor at the time.

Great story!! It brings back many fond memories of the glory days of Husky football. Jim Owens brought respect to West Coast college football. I was only 10 at the time, but to this day, I still remember the players, the Big Ten teams involved in the two Rose Bowl victories and even the scores. Thank You for sharing this memorable moment in Seattle sports history.

They were Purple People Eaters before the Vikings claimed the name Purple People Eaters. Great times and memories provided by great players. Still prefer the purple to the black.