By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

During the many decades that the Seattle Post-Intelligencer sponsored the annual Sports Star of the Year awards (1935-09), the newspaper largely confined its list of winners to the top male and female athletes from the previous year. But when the Seattle Sports Commission took over after the P-I bellied up in 2009, it immediately added several new categories for recognition.

The Keith Jackson Award, named for the famed sportscaster, goes to a member of the media for “communicating the sports stories of Washington.” Its winners include Bob Robertson, Bob Rondeau and the late Dave Niehaus. The Wayne Gittinger Inspirational Award is given to “an inspirational young athlete who has overcome major medical obstacles to inspire others.”

The Paul Allen Award is presented to “an individual who has made a significant or compelling contribution to the local community.” Jamie Moyer, Detlef Schrempf and Lenny Wilkens are previous winners.

The Royal Brougham Legend Award is “given to an individual for a lifetime of achievement in sports and exemplifies the spirit of Washington.” Prior winners include Marv Harshman (2009), Don James (2010), Bob Houbregs (2011), Edgar Martinez (2012), Bobo Brayton (2013) and Elgin Baylor (2014).

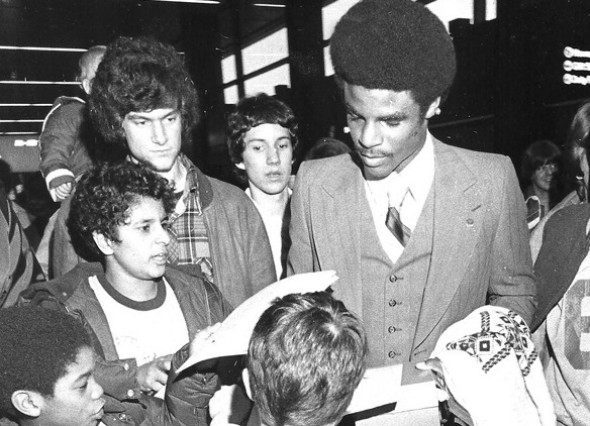

Brougham, who pecked at his Post-Intelligencer typewriter for 65 years, created what was then called the ‘Man of the Year Award” in 1935. Brougham made his final presentation to the winner in January of 1978, only months before his death, to University of Washington quarterback Warren Moon, who won after directing the Huskies to an upset victory over Michigan in that year’s Rose Bowl.

Wednesday night, at the 82nd Sports Star of the Year celebration at the Paramount Theatre (purchase tickets here), Moon will be feted again, appropriately with the Royal Brougham Legend Award. He will become the first football player to win it, also appropriate since no one with ties to the state of Washington ever left a larger footprint on his game.

Start with the legacy Moon left at Washington, at which he arrived in 1975 as a transfer from West Los Angeles Junior College.

The “James Era,” the greatest period in Washington football history, didn’t begin with James’ hiring in 1975, or even in 1976. It launched, although no one knew it then, Oct. 8, 1977 with James sporting a record of 12-14 in two-plus seasons, including a 1-3 mark to open 1977. Both the team and program seemed headed for another debacle.

Attendance dropped from an average of 59,531 during the Sonny Sixkiller era (1970-72) to 42,595 in 1976. Part of the fade had to do with the sudden popularity of the expansion Seattle Seahawks, part of it was that Washington had not produced a Rose Bowl team since 1964. And 1977 seemed to be devolving into another one of those years after losses to Mississippi State, Syracuse and Minnesota in the first four games.

“We got off to a slow start,” said Moon. “There were two games we probably should have won. There were some guys on the team that tried to take advantage of the rules and that really distracted our football team. The thing that we wanted to accomplish at the beginning of the season was to win the Pac-8 and go to the Rose Bowl. It was right there in front of us, but we had to start that week at Oregon.”

The Huskies rolled into Eugene and smashed the Oregon Ducks 54-0, running 92 plays to Oregon’s 58.

“Our success today came from Moon’s great reads at the line of scrimmage,” James told the Post Intelligencer after game. “He must have made 15 or 20 checks.”

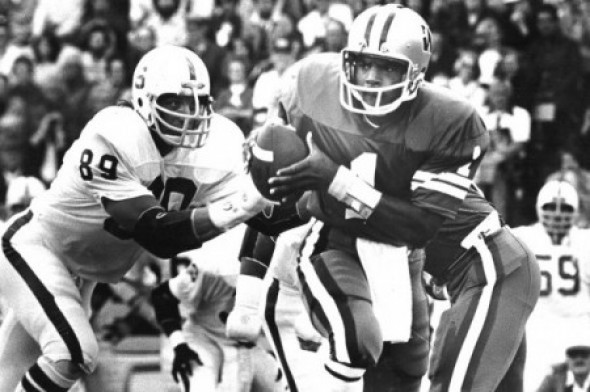

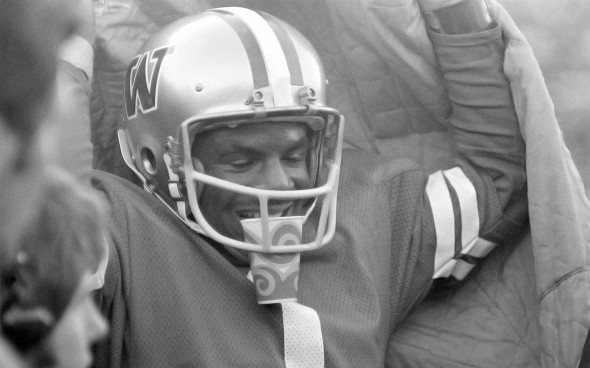

The win flipped Washington’s season. Led by Moon, who became the Pac-8 Player of the Year, the Huskies tore through the rest of their schedule and earned a trip to the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, where they scored a major upset over Michigan with Moon earning the MVP award.

In the aftermath, James and his staff were able to recruit a core of players that, over the following four years, led Washington to a Sun Bowl, two more Rose Bowls, an Aloha Bowl and the No. 1 ranking in the Associated Press poll for seven consecutive weeks in 1982.

“In our first couple of years, we did a great job in the Northwest of getting blue-chip players,” said Skip Hall, a long-time James assistant. “Then we were able to bring in some arms and legs from California. We got the heart and soul from the Northwest and the arms and legs from California. We were able to branch out.”

More than a decade later, in 1990, James was asked to reflect on his early UW days, which had a co-national championship in its future (1991).

“If we don’t win that (1978) Rose Bowl, probably things don’t play out nearly as well,” James admitted. “I don’t even want to think about what would have happened if we hadn’t turned our season around in Oregon. And then winning the Rose Bowl changed everything.”

Elaborating, James remarked, “Warren Moon was probably the most significant player I ever brought into our program.”

It wasn’t easy on Moon. Many UW boosters didn’t like the idea of James playing an African American quarterback. Also, playing junior college ball in LA, Moon threw the ball all over the place. At Washington, he was asked to be a different kind of quarterback, one that was not permitted to use his primary gift, a great arm.

“I second-guessed my decision to come to Washington a lot of times when I was there because I didn’t feel like I was being used to the best of my ability,” Moon said. “But I also understood we were building a program and that we didn’t have a lot of talent around us.

“I needed to transform myself into the type of quarterback (James) was looking for and fit into the philosophy that he was trying to coach at that particular time with the talent that we had.”

Watching Moon later throw for nearly 300 touchdowns in the NFL makes one wonder retroactively why he was only called upon to pass 12 to 15 times a game as a Husky. Still seems like a misuse of resources, a contention with which Moon doesn’t disagree. It cost him.

Since he came from James’ run-first program, some scouts speculated that Moon would not be able to adapt to the NFL’s passing game, and might have to play a position other than quarterback. Moon didn’t want to do that.

Then, of course, there was the double stigma of Moon being an African American. The NFL in those days didn’t believe African Americans could play quarterback at a high level. Several tried, but only James Harris had achieved any measurable success.

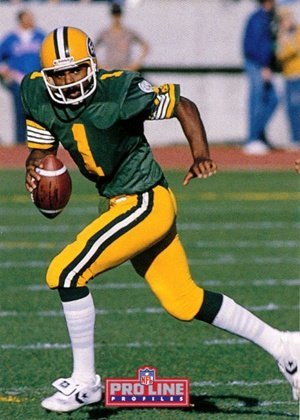

So Moon signed with the Edmonton Eskimos of the Canadian Football League and emphatically made the case that an African American quarterback could indeed succeed on the professional level. He helped lead Edmonton to five consecutive Grey Cup titles (no team since has won more than two) and ended his career in the league in 1983 with a slew of awards, including 1980 Grey Cup MVP, 1983 All-Canadian quarterback and 1983 CFL MVP.

A free agent in the truest sense entering 1984 (no NFL team selected him in 1978 in a draft that lasted 12 rounds), Moon had an opportunity to join the Seahawks that year. They offered him a contract. But the Houston Oilers offered him a better one, guaranteeing the majority of the deal, something the Seahawks were unwilling to do.

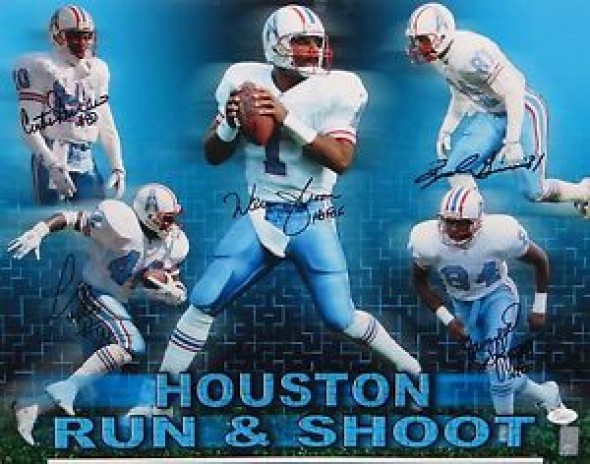

From 1987 through 1993, the Oilers never ranked worse than 10th in total offense. From 1990-93, they also ranked second, third, second and third in scoring offense. With Moon at quarterback, the Oilers reached the playoffs every year from 1987-93. After he departed for Minnesota in 1994, the Oilers did not reach the postseason again for five years, when they were based on Tennessee, rebranded the Titans.

Moon’s Oilers never advanced beyond the divisional round of the playoffs, but not for a lack of production at his position. In his 10 postseason starts, Moon averaged 287 passing yards and an 84.9 rating. By contrast, during his playoff career, Dan Marino averaged 250.6 and 77.1. John Elway averaged 225.6 and 79.7, and Jim Kelly 227.2 and 72.3.

From 1987 through 1995, Moon exceeded 4,000 passing yards four times (1990, 1991, 1994, 1995), topping the NFL with 4,689 in 1990 and 4,690 in 1991.

Unlike Moon, who played with four franchises (Houston, Minnesota, Seattle, Kansas City), Marino spent his entire career in Miami while Elway spent his in Denver.

“Four franchises and four different offenses,” said Moon. “I would have loved to have been in the same offense like Peyton Manning, Joe Montana, Steve Young and Tom Brady for pretty much a whole career. That’s why those guys were so successful in their offenses because they were in the same system for so many years and got a chance to learn how to command them the way they needed to.

“But I was able to adapt and was pretty productive in all the offenses. A lot of quarterbacks can’t adapt. They are made for certain systems. I could play wherever they put me and could do what I was asked to do. My versatility really helped me. I’m more proud of that than the numbers.”

The numbers: 49,325 yards, 297 touchdowns and 49 300-yard games (eighth all-time) out of the 208 he played. Moon cited two of those games among his most memorable. One occurred Oct. 26, 1997 when he was in the first of two seasons with the Seahawks. He threw for 409 yards and five touchdowns in a 45-34 Seattle victory over the Raiders.

The other, and topping the list, came Dec. 16, 1990 at Kansas City on a sleet-filled day and in a venue, Arrowhead Stadium, that ranks among the toughest in the league for visiting teams. Moon threw for 527 yards and three TDs against a Chiefs secondary that included four Pro Bowlers. He probably would have broken Norm Van Brocklin’s single-game record of 554 if he hadn’t taken himself out of the game.

“I didn’t want to stay in and keep throwing the ball. We had the game in hand. I’d hurt my finger so it was bothering me. There was no need to stay in,” Moon said. “They told me how close I was to the record, but I didn’t want to throw it just to try to set a record. If it was part of the flow of the game, then I would do it. But I felt like we might play that team again in the playoffs.

“Those are the games where it seems everybody is in slow motion and you are at another speed. You feel like you can’t miss with your throws. Guys make plays after the catch, and that helps, but you’re putting the ball where you need to put it.”

Much was made over the past two weeks about 39-year-old Peyton Manning reaching the end of his career, winding up as a game manager. By contrast, Moon put together three of the top 10 passing-yardage seasons in NFL history after the age of 35. In his age-41 season (1997), Moon threw for 3,678 yards and 25 touchdowns, only a part of his NFL legacy, a snapshot of which looks like this:

- First African American quarterback to start in the Pro Bowl (1988).

- First African American QB named NFL Man of the Year (1989).

- First African American QB to lead the NFL in TD passes (1990).

- First African American QB named AP Offensive Player of Year (1990).

- Only African-American QB to throw for 500 yards in a game (1990).

- First African American to lead the league in TD passes (33) and exceed 4,000 yards in a season (4,689), both in 1990.

- Oldest (40) to throw for 400 yards in a game (1997).

- Oldest (40) to throw five TD passes in a game (1997).

- Oldest (40) to rush for an NFL TD (1997).

- Oldest (41) Most Valuable Player in Pro Bowl (1998).

- Oldest (43) to throw a touchdown pass (2000).

- First undrafted QB to earn election to Pro Football Hall of Fame (2006), and in his first year of eligibility.

- First African American QB elected to Pro Football Hall of Fame (2006).

- Only player in CFL Hall of Fame (2001) and Pro Football Hall of Fame (he’s also in the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame).

“I felt like my numbers were Hall of Fame worthy. They were better than a lot of guys already in there,” said Moon. “I always felt like I might get in one day. I was honored and a little taken aback that I got in on the first ballot.”

Such was the level of his play that Moon entered Canton without a Super Bowl ring, a feat that will be difficult for another quarterback to duplicate.

It is taken for granted now that African Americans can succeed spectacularly at quarterback, a fact underscored by Cam Newton and Russell Wilson this past season. But Moon was the first to prove it. He seems of two minds about that accomplishment.

“I feel like I was a good enough quarterback no matter what color I was, but I did happen to be the first African American to do those things. So I was proud because it was an accomplishment for African Americans. I think when an African American does something for the first time that’s significant, it should be recognized. But once it’s done, we don’t need to make a big deal about it anymore.”

As for his Royal Brougham Legend Award, Moon said, “It reminds me that I’m old. If you’re not dead, you’ve got to be old to win something like this. I know some of the people who have won this award, and to be in that type of company is quite an honor. I’m proud that I did something well over a long period of time. I feel like what I’ve gotten in my career I’ve really earned, but you never know that you deserve certain things that are bestowed upon you unless other people tell you that.”

Other people will tell Warren Moon that he is much deserving of his legend status Wednesday night.

—————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

5 Comments

A well deserved honor for Warren and it’s appropriate that both he and Don James have been awarded this honor. Warren has been a big part of the Seattle sports community throughout the years and I enjoy his work with Steve Raible for the Seahawks. It’s rare when you get a radio broadcast team as connected to the community and it’s history as they are. It’s great to have two broadcasters who can pronounce Puyallup and also know how to get there. I have always been disappointed that the Hawks never drafted Moon when he left UW.

I used to think Warren might have a career in politics when his football career ended, his ability to work with people and penchant for public speaking would greatly work in his favor, however he seems very satisfied with his career today and everyone in Washington benefits from it.

I can still remember how upset I was when the Seahawks allowed Houston to outbid them for Moon in 1984. I’ve forgotten most of the Seahawks big boo-boos, but not that one. For me, it was their worst one. At least we later got the privilege his last couple years and now continuing with Raible as part of the great radio team they are. But I keep thinking what it could have been if we would have had one of the great ones his whole career.

That has always been one of my “big ifs” for Seattle sports. Nothing against Dave Krieg, I always loved the guy, but he was so unbelievably inconsistent. I have always believed that if Seattle had signed Warren Moon instead of letting him get away and go to Houston, that there is a very good chance that team in the 1980s would have one a Superbowl or two. They were that good and Warren was that good too. Can you just imagine the combination of Moon to Largent? And with a great coach like Chuck Knox and Curt Warner at tail back, along with that great defense? Oh man, it would have been something.

I get what you’re saying about Mudbone but I put some of the blame on Mike McCormack and Chuck Knox. The team got old and they didn’t address that until 1987. Look how long Green-Nash-Bryant were the D-Line. For years Largent had a revolving door on the other side of the field at WR. And the O-Line then was like the O-Line now. Better drafting and not being so loyal to older players would have made a world of a difference.

I can’t remember to many of the day to day details of that team but one year that has always stuck out to me was 1986 when they started the season so poorly and then suddenly got hot on Thanksgiving Day by whipping out the Dallas Cowboys. They then went on a 5 game winning streak, including wins over the eventual Superbowl teams in the Giants and Broncos, but finished the season 10-6 and missed the playoffs because of the games they blew early in the season. I also thought it was the Seahawks fault the Patriots got whipped by the 85 Bears because they didn’t belong there, it should have been the Seahawks in that game.

Those players weren’t that old, most were still in their mid twenties and that point.