In mid-December 1925, 90 years before Stanford’s Christian McCaffrey and LSU’s Leonard Fournette said they would skip 2016-17 bowl games in order to prep for the NFL draft, University of Washington running back George Wilson pulled aside his coach, Enoch Bagshaw, and told him that he did not want to play in the 1926 Rose Bowl against Alabama.

Wilson explained that he had received “lucrative” offers to turn professional and was particularly considering one from a promoter named C.C. Pyle that would showcase him in a series of exhibition games opposite Illinois All-America choice Red Grange. Wilson did not want to risk injury in the Rose Bowl and lose out on the paychecks.

A “panicked” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s description) Bagshaw did not want to play Alabama without Wilson, his star player, and denied Wilson’s request. Wilson responded by convincing his teammates to shun the Rose Bowl.

UW president Henry Suzzallo and graduate manager (athletic director) Darwin Meisnest hurriedly met with UW players in Suzzallo’s office. After Suzzallo and Mesinest argued for going to the game, Mesinest called for a vote of the players.

They unanimously said no, explaining that a Rose Bowl trip would entail an additional month of practices and Christmas away from home. Besides, they reasoned, Washington had already been to the Rose Bowl, against Navy in 1924. Meisnest pressed the issue, but the players again rejected the trip.

No reason surfaced for several years as to why Wilson and his teammates ultimately changed their minds. But they did. As Wilson feared, he was hurt, almost certainly costing Washington a national championship.

Even with the 20-19 loss to Alabama, the 1925 Huskies still rank among the greatest teams in school history.

Washington roared through its 11-game schedule 10-0-1, scoring 461 points to its opponents’ 39 (UW outscored 13 foes this year 578-224). Only a 6-6 tie at Nebraska, UW’s first game east of the Rockies, marred the season. The Huskies had six shutouts, including a 108-0 wipeout of Willamette in a game UW led 28-0 before Willamette ran an offensive play (after each UW score, the Willamette captain curiously elected to kick off rather than receive).

Unlike 1923, when the Rose Bowl selection committee picked Washington only after California declined an invitation, the committee had no misgivings about inviting the 1925 Huskies. It wanted to match Washington against undefeated Dartmouth, but the Hanovers declined, citing the same issues (travel, Christmas, extra practices) as the Huskies.

Princeton and Colgate also turned down Rose Bowl invites, forcing the committee to seek out fourth option Alabama, which accepted eagerly.

“I put it to my players,” Alabama head coach Wallace Wade told the New York Times. “Going to the West Coast was a big thing. It would take us five days on a train from Tuscaloosa. I told them it would deprive them of their Christmas vacation and that they would have to stay in training another three weeks. It took them about two minutes to make up their minds.”

Alabama-Washington was widely considered the worst mismatch in Rose Bowl history. Although Alabama won nine consecutive games, the consensus was that southern football was not on a par with the rest of the country. The newspapers installed the Huskies as three-touchdown favorites, making them exactly the kind of foregone-conclusion winner that Alabama is considered in Saturday’s Peach Bowl in the Georgia Dome.

To Bagshaw’s alarm, as reported by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, his players largely agreed with the newspapers: Alabama was jayvee material when compared to Washington.

“The Washington players act as if the Rose Bowl game is nothing more than a light workout,” the P-I reported a week before the game.

Alabama couldn’t convince anyone, even Glenn “Pop” Warner, the famous Stanford coach, that it had a chance.

“They’ve got speed,” Warner said of the Crimson Tide. “But they’re too light to stop that big Washington team,” Washington having beaten Stanford 13-0 weeks earlier.

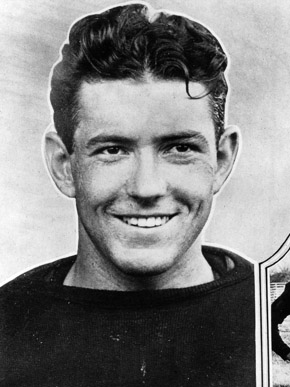

Warner invented the single- and double-wing formations, introduced the three-point stance, helped pioneer the forward pass, and coached Jim Thorpe at Carlisle and Ernie Nevers at Stanford. But he wholly underestimated Alabama and its star runner/receiver, Johnny Mack Brown, a native of Dothan, AL., known in those parts as “The Dothan Antelope.”

Warner and the various newspaper predictors got things right – in the first half. UW halfback Harold Paton, a sophomore, scored on a one-yard run after Wilson’s interception set up a 63-yard drive. QB George Guttormsen missed the extra point on a drop kick. But Wilson broke free minutes later for a 36-yard run and would have scored if Brown hadn’t stopped him at the 22.

On the next play, Wilson threw a touchdown pass to John Cole, but another Guttormsen drop kick clanged off the crossbar. Washington hit halftime with a 12-0 lead.

Early in the second half, Wilson suffered bruised ribs, forcing him from the game. In less than seven minutes, Alabama scored three touchdowns, two by Brown on receptions of 61 and 30 yards, giving the Tide a 20-12 lead. Bagshaw rushed Wilson back in the game. He threw a 27-yard touchdown pass to Guttormsen, but Washington could get no closer than 20-19.

“We not only won the Rose Bowl,” Brown said after the game. “We won the Rose Bowl for the whole South.”

Washington might have won — on the occasion of college football’s centennial in 1969, the game was voted one of the 10 best — if Wilson hadn’t spent so much time on the sidelines with the rib injury.

He had two TD passes, set up another with a 25-yard run, rushed for 134 yards, had an interception and made, according to unofficial press box statistics, 10 tackles in less than 20 minutes.

Washington gained 317 yards and scored all of its points with Wilson in the game. With Wilson out for 22 minutes, Washington gained 17 yards and surrendered 20 points.

“As Wilson went, so went Washington,” wrote The Associated Press. “The Washington All-America was all of his team’s offense, if not all of the Washington team.”

Damon Runyan, a New York sports writer in the 1920s who became famous in the 1930s for his short stories that inspired Broadway’s Guys and Dolls, covered the game and wrote this about Wilson from his press box perch: “The Washington All-American is one of the finest players of this or any other era. Wilson is a one-man team.”

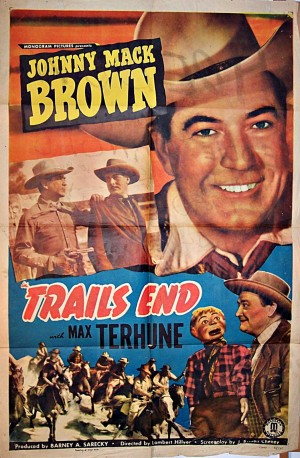

But Johnny Mack Brown earned Player of the Game honors and received so much attention for the role he played in the mega upset that Wheaties splashed his photograph on its cereal boxes. That led to a screen test and a motion picture contract with MGM.

Brown debuted in Slide, Kelly, Slide (1927) with William Haines in a film about baseball. That was followed by The Bugle Call (1927), which starred Jackie Coogan (later Uncle Fester in The Addams Family). In 1928, Brown appeared in the last Norma Shearer silent film, A Lady of Chance. He later worked with Greta Garbo, Marion Davies and Mary Pickford, the latter in Coquette (1929), for which Pickford won an Oscar.

Brown appeared in more than 160 films – many of them Westerns — between 1927 and 1966, as well as a smattering of television shows, in a career that spanned nearly 40 years. He earned a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6101 Hollywood Boulevard in 1960, three years after his induction into the College Football Hall of Fame.

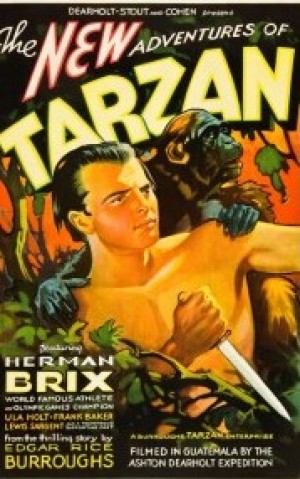

Tacoma native Herman Brix played tackle for Washington in the 1926 Rose Bowl and enjoyed a movie career nearly as long as Brown’s. After competing in track and field at the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam – he won a silver medal in the shot put – he returned to Southern California and competed for the Los Angeles Track Club, three times setting the world shot record between 1929-33.

In the midst of his track career, Brix took a screen test at the urging of swashbuckler Douglas Fairbanks Sr., and probably would have landed the starring role in Tarzan The Ape Man in 1932 had it not been for a shoulder injury (the part went to 1928 Olympic teammate, swimmer Johnny Weismuller). But two years later, Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs endorsed Brix to star in The New Adventures of Tarzan.

Brix, who later changed his screen name to Bruce Bennett, appeared in more than 100 films, including Million Dollar Legs (1932 with W.C. Fields), Riptide (1934, Norma Shearer) and Treasure Island (1934, Lionel Barrymore, Jackie Cooper).

Brix/Bennett also received leading roles in World War II action films such as Atlantic Convoy (1942) and Sabotage Squad (1942) and became a secondary leading man in several “women’s pictures” such as Mildred Pierce (1945) as Joan Crawford’s ex-husband, as well as A Stolen Life (1946) with Bette Davis, Nora Prentiss (1947) with Ann Sheridan and The Man I Love (1947) with Ida Lupino.

Brix/Bennett took his most substantial role in 1948 when Humphrey Bogart, with whom he had starred in Sahara (1943) and Dark Passage (1947), pushed for him to play the role of ill-fated gold prospector James Cody in the John Huston-directed The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Bennett beat out Ronald Reagan for the part.

With their burgeoning film careers, coupled with the low wages pro football offered in those days, neither Brown nor Brix bothered with the game after the Alabama-Washington Rose Bowl. But Wilson did.

He starred during a five-game barnstorming tour with Red Grange in January 1926, played for the Los Angeles Wildcats – also called “Wilson’s Wildcats” — of the first American Football League, and led the Providence (RI) Steam Roller to the 1928 NFL championship.

For many years, Wilson bore a public grudge against Washington, claiming the school reneged on cutting him in on the gate receipts for the 1926 Rose Bowl, his price for playing and the reason he changed his mind about participating. Washington officially denied Wilson’s claim, saying it offered no such thing.

Wilson never backed off the claim. Washington always refused to acknowledge he had one. But the school pulled a lot of strings to help Wilson, a recovering alcoholic, financially, in the years before his death from a heart attack in 1963.

As for Alabama, declared the national champion after its win over Washington, no one sneered at the Tide or Southern football again.

Southern teams played in 13 of the next 20 Rose Bowls and today they dominate the business of bowl games.

In its official sloganeering, Alabama still refers to the 1926 Rose Bowl as “The football game that changed the South.”

It probably did. And here we are 90 years later for a Washington-Alabama rematch.

8 Comments

Great piece, love the history lesson.

Steve, Damon Runyan was famous for his short stories in the ’30s, but not for the Musical “Guys and Dolls.” It opened in 1950 with music and lyrics by Frank Loesser and script by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows, based on several of Runyan’s stories. One of those songs, “Luck, Be A Lady Tonight,” could well be the Huskies’ theme song against Alabama.

Lots of pay-for-play intrigue, then as now.

agreed, excellent read, very interesting, and yes – George Wilson was way ahead of his time asking for a piece of the action. NCAA and schools have had it their way for nearly a century . . .

Sounds like Johnny Mack Brown was Joe Willie Namath before there was a Joe Willie Namath! At least from a celebrity standpoint.

I was vaguely aware of his music, not his football. But I was intrigued to read that Wilson was as upset about not getting a cut of the action in the 1920s as players should be today.

Good stuff!

Google is paying 97$ per hour! Work for few hours and have longer with friends & family! !mj152d:

On tuesday I got a great new Land Rover Range Rover from having earned $8752 this last four weeks.. Its the most-financialy rewarding I’ve had.. It sounds unbelievable but you wont forgive yourself if you don’t check it

!mj152d:

➽➽

➽➽;➽➽ http://GoogleFinancialJobsCash152ShopHouseGetPay$97Hour… ★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★✫★★::::::!mj152d:….,…..