A seminal anniversary in Seattle sports history passed quietly Saturday — the day 20 years ago that seeded the town’s two most recent national pro-team championships. Newbies and youngsters, pay attention: The Seahawks and Sounders have become two of the most formidable franchises in North American sports because of what happened on June 17, 1997.

In a one-ballot-measure special election, a paper-thin majority of voters across the state of Washington said yes to a set of user taxes that provided $300 million to Paul Allen to build a football/soccer stadium and exhibition center.

That catalyst helped create three Super Bowl teams and an NFL championship in 2014, as well as an MLS Cup winner in 2016. The building also houses fan bases acclaimed as creators of the best home field advantage in their respective sports.

“Magical,” said Fred Mendoza, a Seattle lawyer and a key player in the 1997 drama. “How everything worked out is . . . magical.”

The series of events that led up to the pivot point is so improbable that Mendoza’s invocation of the paranormal is apt. The Sounders’ birth and growth alone will fill a boxcar with preposterousness.

“There were about 20 things that had to happen the way they did, and were worth about five percent each, in adding up to our success,” said Adrian Hanauer, majority owner of the Sounders. “We checked all 20 boxes — 100 percent. It went fantastically well.”

The near-perfect outcomes stand in contrast to so-far-futile efforts to return the NBA to Seattle. In the nine years since the Sonics left, no ground has been broken on a new arena, and prospects for the debut of the NHL are still years away with no clear path yet.

“You lose a team, and it’s incredibly hard to get it back,” said Mendoza, “as we’re seeing.”

In fact, it was the loss of the Seahawks — for two weeks in 1996 — that triggered the absurd sequence that helped produce two champions.

After the first good six weeks of baseball in Mariners history provided not only the franchise’s first playoff team, but $380 million of public funds for a new stadium, Seahawks owner Ken Behring wanted similar treatment for a new football stadium.

But his Seahawks were mediocre, and the Legislature told him to drop dead.

So without permission from Seattle or the NFL, he trucked up the franchise’s goods from Kirkland and moved to the Los Angeles market left empty by the relocations of the Raiders and Rams. A civil suit and NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue forced him back to Seattle.

Allen, the Microsoft co-founder and owner of the NBA Trail Blazers, was implored by local officials to help out by buying the franchise from Behring, a California real estate developer who bought the team in 1988 from the Nordstrom family.

A hoops guy who didn’t know much about football, Allen reluctantly agreed, but with a big stipulation — he would buy the team for $200 million, and throw in $100 million, but the the public needed to contribute $300 million to help replace a damaged and fading Kingdome.

Since the Legislature was still being pilloried for the Mariners’ stadium giveaway in late 1995, a decision was made to put up the stadium funding issue for a statewide public vote. Even in the go-go 1990s replete with federal and state budget surpluses, the idea of voters subsidizing a billionaire’s playpen sounded ludicrous.

But lobbyists cobbled together what amounted to a series of user taxes on admissions, hotels, motels and car rentals that required no general tax funds. Even so, polls on the subject showed skepticism for public funding.

Enter Mendoza, a longtime soccer fan who volunteered his professional time to the Washington State Youth Soccer Association. He had been working on a plan with Michael Campbell, head of the Seattle Sports Council, to secure one of the inaugural franchises in Major League Soccer, which would debut in 1996.

Big problem: No natural-grass stadium fit to host pro soccer.

Reading about Allen’s football-stadium proposal, he called Bert Kolde, Allen’s longtime friend and consigliere. In a subsequent meeting, Mendoza and Campbell asked Kolde what he thought about a plan, in exchange for sharing the stadium, of drawing the electoral support of the state’s robust soccer community.

“Gentlemen,” Mendoza recalled Kolde saying, “This is a great idea.”

Lobbyists rushed to Olympia to re-write the legislation to include pro soccer with pro football. Armed with a commitment from Allen to subsidize the cost of staging the election for $4 million — the first and only such private funding in state history — Mendoza and Campbell whooped when the Senate voted 28-21 to authorize the vote on an open-air stadium on the site to be vacated by the Kingdome.

But the vote would come in less than three months.

Organized by one of Seattle’s legendary public relations masters, Bob Gogerty, Mendoza, Kolde and Bob Whitsitt jumped in the Seahawks president’s Mercedes and began driving around the state, meeting politicians, community leaders and soccer organizations to seek their support.

Mendoza recalls going to innumerable Saturday morning soccer tournaments, dragging along a box, upon which he would stand with a microphone and a tinny speaker, preaching.

“Heady times,” Mendoza said, chuckling. “My law partners asked, ‘Are you ever coming back to work?'”

The polls said the eastern side of the state was largely opposed, meaning that the four populous west-side counties — Snohomish, King, Pierce and Thurston, where youth soccer was popular — would have to carry the day.

They did. A surprisingly high turnout for a single-issue election, 51 percent of eligible voters, approved the measure by a 51.1 percent plurality, a difference of 36,780 votes. The post-election party was scheduled for King Street Station, where Mendoza had arrived early and anxious.

“The Times and P-I endorsed the project, and finally Gov. (Gary) Locke supported it, as did (ex-governor and senator) Dan Evans,” he said. “Most businesses liked it, but I was uncertain and real nervous. The early mail returns from the east side showed only 40 percent yes. So we waited late until the King County ballots came in.”

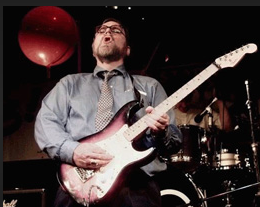

That’s when wannabe rocker Allen emerged on a stage, guitar in hand, smile on his face. His band, “Grown Men,” serenaded the assembled and the party was on.

The overwhelming consensus was that the soccer community was the difference-maker. But it took 12 years before the soccer promise was fulfilled.

The Kingdome had to stay in place until the Mariners exited in mid-1999. Then the Seahawks had to move to Husky Stadium — where Allen originally wanted the team, in a stadium upgraded on his nickel for both teams — for two years before the new stadium opened in 2002.

Mendoza was appointed to the board of directors for the Public Stadium Authority that operates the building, a position he holds today. He was there to assure soccer’s interests were heard.

Even though the USL Sounders, owned since 2001 by Hanauer, had the first sports event in the new stadium — “We beat Vancouver 4-1 in front of 25,500 fans; wanna know who scored?” said Hanauer, in the manner of a father witnessing birth — the soccer community grew impatient for the top-tier league.

Shortly after Tod Leiweke was hired by Allen to become Seahawks CEO in 2003, he called Mendoza to have lunch.

“He said, ‘Fred, I’m told you’re the guy I have to make a speech to,'” Mendoza recalled. “He explained to me that Paul remembers the commitment made to soccer, and the commitment soccer made to him. He said he wanted me to understand that he didn’t have permission to pursue MLS until he righted the Seahawks ship.

“He said, ‘I’m with you, but I have to do this first. We need some time.'”

By 2006, the Seahawks became NFC champions and made their first Super Bowl. In 2007, MLS Commissioner Don Garber introduced Hanauer, who unsuccessfully pursued a franchise for Salt Lake City in 2006, to Joe Roth, a big-time Hollywood producer and huge soccer fan.

Roth had choices as to where he would invest, but was aware that the NBA and Seattle were at odds over the Sonics future. When Seattle was awarded an expansion franchise by MLS in November 2007, the Sonics had begun their final season.

Roth said two years ago, “The main reason we chose Seattle was the Sonics were going.”

Hanauer, who took over as Sounders majority owner from Ross last year, agreed.

“I decided it was a good time to participate, even at a franchise fee six times what it had been two years earlier,” he said, referring to $30 million paid for the Sounders against $5 million for Real Salt Lake. “It was good timing for us, not just because the Sonics were exiting, but the Mariners were struggling, the Seahawks slid back. There wasn’t a lot of juice in the market.

“There was definitely a vacuum we were able to fill quickly.”

The Sounders, with Allen as a co-investor supplying the Seahawks’ business personnel, debuted in March 2009, eight months after the Sonics left. In the first season, they more than doubled the MLS record for attendance in a season. In 2010, Leiweke hired a new Seahawks coach, Pete Carroll, and a new general manager, John Schneider.

By 2013 the Seahawks were again NFC champions, but this time won the Super Bowl. The Sounders signed a world-class American player, Clint Dempsey. By 2014, the Sounders left their five-year partnership with the Seahawks and hired their own soccer-specific front office.

In 2015, Hanauer surrendered his GM role, hired his replacement, Garth Lagerwey, and took over for Roth. In midseason 2016, the franchise’s only head coach, Sigi Schmid, was fired, replaced by top assistant Brian Schmetzer.

And on a frozen December night in Toronto, the Sounders, who had zero shots on goal, completed a bewildering turnaround with an even more bewildering game to became MLS champions.

Two champions, one stadium, one precarious, preposterous path.

“Bart Wiley put it best,” Hanauer said of his chief operating officer. “The two best decisions we made as an organization were partnering with Seahawks, and splitting off operations with the Seahawks, to run our own operations and create our own identity.

“The Seahawks had the infrastructure and safety net. All that experience was paramount to launching with success. Tod couldn’t have been a better partner, who didn’t get enough credit for how successful we were.”

It would also appear the state’s voters made a good decision in 1997. The bonds used to fund construction will be retired on schedule in 2021.

Hanauer, who fell under soccer’s spell in 1976 at the Kingdome’s first sports event, the New York Cosmos and Pele vs. the Sounders, still has a hard time believing what has happened.

He recalled leaving the club’s Pioneer Square offices in December for the Sounders’ victory parade starting at Westlake Center, which drew upward of 50,000 fans.

“I honestly didn’t know if anyone was going to show up,” he said. “I’m serious. We saw some people walking with Sounders gear, and I was thinking, ‘Where are they going? Oh, they’re going to the march.’

“Maybe that’s my defense mechanism, not wanting to be disappointed. But seeing that throng of people, with the joy, the passion and connection to the Sounders, that really took me aback. It showed me what an important part of this community the Sounders have become.”

Not only were there two championships from one stadium ordained by a majority of state voters, the successes also germinated from deep local roots, without anyone noticing.

The three major pro sports ownerships are now led by Seattle natives who went to high school here: Hanauer at Mercer Island, Paul Allen at Lakeside and John Stanton, a Newport High School grad, who took over the Mariners’ majority ownership last season.

If basketball fan and Seattle native Chris Hansen one day were to acquire ownership of an NBA team, the Blanchet student and Roosevelt High School grad would make it four.

Given all the business and competitive travails, often emanating from out-of-town ownerships, that attended Seattle’s sports franchises in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, plus the 2008 loss of the Sonics, June 1997, when the local guys won, was the turn from the valley toward the pinnacles.

18 Comments

Back in ’97 I worked in a building in Bellevue where one of Paul Allen’s companies was located. I went to their office and asked for some pro-stadium posters and stuff, and got permission from my HR department to put it up in our lunchroom. I lobbied my co workers to vote yes. I also got to touch the boxes that Jimi Hendrix’s guitars were shipped in, but that’s another story.

It’s funny that the Sounders thought they were going to fill a void with the SuperSonics leaving and the Hawks and M’s not being great. I happen to be a fan of all 3 teams, but some of the most die hard sounders fans don’t pay any attention to the M’s and Seahawks. .

It’s not so much that soccer fans are basketball fans, or vice versa. It’s that all the sponsorship money that went into the Sonics now was in play. The Sonics absence wasn’t about attendance or fandom as much as sports marketing.

Makes sense. Thanks.

And thanks for getting the comments back to normal. I had to un-bookmark you for a while it was so annoying.

I don’t think I had much to do with that. I suspect you’ve learned to gird your loins.

Thank you for writing this interesting and important history lesson, Art. Such an important milestone in the quality of life here in the Puget Sound. Interesting to compare, in my case, to San Diego where my parents moved late in Dad’s career and where they lived after retirement. Another large market which went the other direction and is left only with a struggling MLB franchise. Things could have turned out much differently here.

Just as an aside, I’ve heard Tim Eyman say in interviews that it was the Ms strong arming the state legislature in doing an end run of the King County vote that inspired him to get involved in politics. So I guess this series of events also left us with a dark outcome as well. Lol.

It’s true that the M’s stadium funding launched the anti-subsidy movement with Eyman as its demon spawn. Putting up nearly every new tax to a public vote reduces the entire point of the state legislature.

The first initiative Eyman worked on was Initiative 200, the anti-affirmative action measure, in 1998.

Perhaps true, although he claims that the stadium funding inspired him. Whether that meant he volunteered, or just watched, I don’t know.

I volunteer at a community radio station in Everett and engineer a call in program where we interviewed him for the full hour and took calls. The story of what inspired him to get involved in politics came straight from him in the course of our interview.

Of course those events with the vote and legislature override came in late ’95 and early ’96.

I just wish Mendoza would’ve held his line on the natural grass requirement.

A grass field in this climate wouldn’t hold up for both teams, which play in Oct/Nov/Dec.