By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Editor’s note: The potential arrival of a National Hockey League franchise in 2020 in a renovated Seattle Center arena has prompted Sportspress Northwest to present a six-part series revisiting the sport’s Seattle history from previously published Wayback Machine stories. Part 4 next Wednesday: The Totems’ Bill MacFarland: Player, coach and lawyer.

An odd thing happened to hockey icon Golden Guyle Fielder the most recent time he visited Seattle in 2008. En route to his induction ceremony into the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame, Fielder couldn’t locate KeyArena, his enshrinement site, even though played for several years in the facility, known in Fielder’s heyday with the Seattle Totems as the Center Coliseum.

“I just had an awful time trying to find that place,” said Fielder, bollixed by construction and one-way streets that altered the navigation of the lower Queen Anne neighborhood since his residency there in the 1960s. Imagine his surprise at the changes wrought in the past 10 years.

(Fielder will, in fact, be in town in 10 days, and you can have lunch with him. See details at the end of the story.)

Even odder than Fielder losing his bearings on induction night: It not only took 40 years for him to receive recognition that should have come his way about the time of the Watergate hearings (1974), but 13 members of the Pacific Northwest media entered the state Sports Hall of Fame ahead of the greatest hockey player ever to crease a sheet of ice in Washington.

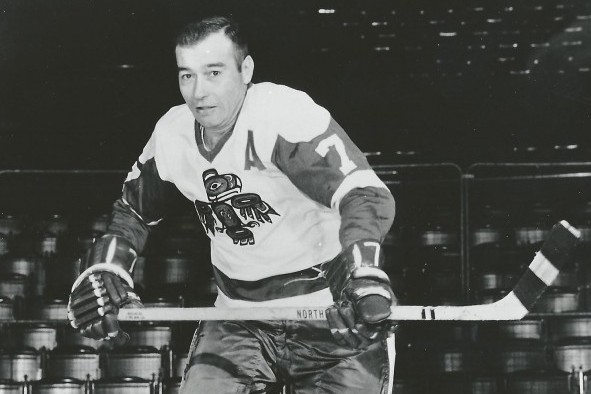

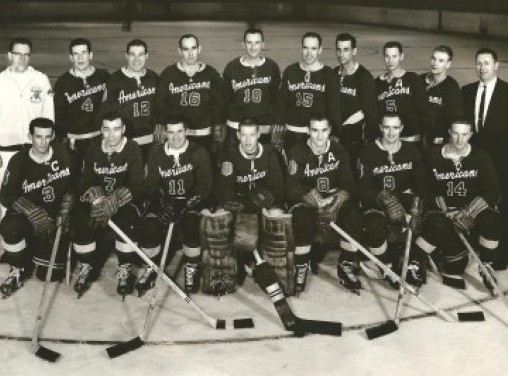

Fielder starred for the Seattle Bombers in 1953-54, for the Seattle Americans from 1955-57 and with the Totems from 1957-69. He would have had a 16th but Seattle, stumbling financially, did not field a hockey team in 1954-55. During that time, the Totems played in five Western Hockey League finals and won three championships, Fielder serving as the centerpiece as team leader and incomparable stats machine.

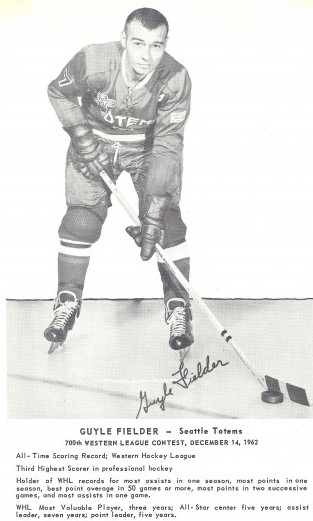

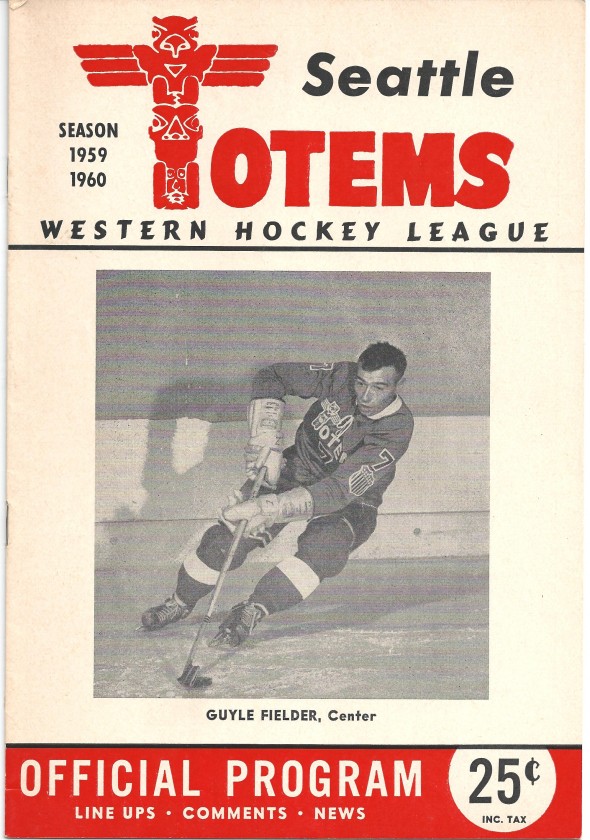

Fielder topped the WHL in assists 12 times and in points nine times. He received 11 All-Star salutes, captured six Leader Cups as the league’s Most Valuable Player, and three Fred J. Hume Cups as its Most Gentlemanly Player. In 1956-57, playing for the Americans, Fielder became the first professional hockey player to produce 100 points in a season (122), a feat he replicated three times. In other words, he racked up Wayne Gretzky-like numbers two decades before Gretzky. His career point total — 1,929 – is still the minor league record nearly four decades after his final pro contest.

That a player so clearly gifted spent his entire career in the minor leagues, except for 15 National Hockey League appearances spread among the Chicago Black Hawks (3 games) Boston Bruins (2) and Detroit Red Wings (10), is an enigma that has baffled the hockey cognoscenti for decades, especially since Fielder has always been considered the greatest player of his time not named Gordie Howe, Maurice Richard or Jean Beliveau.

Fielder offers several reasons for his missing out on the NHL, not the least of which is that all he wanted to do was play. The WHL provided that opportunity while the NHL could not.

The NHL had six teams in Fielder’s era, so jobs were scarce. Fielder was small, 5-foot-9 and 160 pounds. While he had remarkable offensive instincts, especially when it came to passing, stick handling, intuition and anticipation, his style ran contrary to the NHL’s overwhelming orientation to defense.

It’s probably language abuse to suggest Golden Guyle played with guile but, in fact, he did. Still, the NHL simply found his game too unconventional. So Fielder, who believed in handling the puck and setting up his wingers, never found an NHL fit.

Originally signed by the Chicago Blackhawks as a free agent March 9, 1951 (the 20-year-old Fielder received a $100 signing bonus), Fielder saw action in three games (no points) before Chicago loaned him to New Westminster of the Pacific Coast Hockey League for cash in August 1951. The Blackhawks traded Fielder to Detroit in 1952, which waived him a year later.

Claimed by the New York Rangers, Fielder spent one, out-of-season month with the Rangers before they traded him to the Seattle Bombers prior to the 1953-54 season for the rights to a prospect named Lee Hyssop (who never did much) in what turned out to be one of the greatest deals consummated by a Seattle professional sports franchise. Fielder received one more shot at the NHL, prior to the 1957 season.

“I had a good tryout in Detroit in 1957,” said Fielder. ”I went all through training camp – I played with Gordie Howe – but we got off to a terrible start. I went to the second line, the third line and then to the bench. I told Jack (GM Jack Adams) that I was wasting my time and his time. Anybody can sit on the bench. Jack gave me a $500 raise, and I stuck around a few more games. Then I wasn’t even dressing. I told Jack, ’Just get me out of here. We’re wasting each other’s time.’ I like to think that I could have played in the NHL. I was a little smaller, but agile. I just didn’t have the patience to stick. I only wanted to play, and to the best of my ability.”

The Western Hockey League offered Fielder an opportunity to maximize his skill set. So Fielder, Idaho born (Nov. 21, 1930) and Saskatchewan reared, returned to Seattle, where the Bombers had been renamed the Americans, and helped launch the second great age in Seattle hockey, the first between 1915-24, when the Seattle Metropolitans played for the Stanley Cup three times in a four-year span, winning the prize in 1917.

In 1956-57, playing on an Americans squad that included future Vezina Trophy winner Charlie Hodge, future NHL general manager Emile ‘The Cat’ Francis, and Ray Kinasewich, who tallied 44 goals, Fielder shattered the professional single-season scoring record with 122 points en route to claiming MVP accolades and the first of four consecutive scoring titles.

A year later, the Americans defeated New Westminster in the first round of the playoffs, Seattle’s first postseason series win since 1948-49, when the old Ironmen represented the city in the Pacific Coast Hockey League.

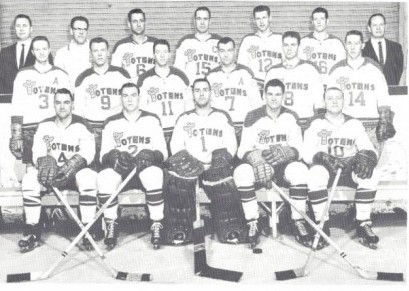

For the 1958-59 season, the Americans became the Totems. Fueled by All-Stars Fielder, Val Fonteyne, Gordie Sinclair and Bev Bentley, won their first WHL title, sweeping the Calgary Stampeders 4-0.

Although the Victoria Cougars swept the Totems in the 1959-60 playoffs, Seattle featured one of the most offensively talented teams in league history, the only season in which the WHL’s three leading scorers — Fielder (95 points), Bill MacFarland (86) and Rudy Fillion (85) – came from the same club. Also, Marc Boileau and Tom McVie finished sixth and seventh.

The Totems reached WHL finals in 1960-61 (lost to Portland) and 1962-63 (lost to San Francisco). Sandwiched between was a year (1961-62) in which MacFarland paced the league with 46 goals and was MVP.

With MacFarland becoming head coach in 1966-67 (the team vacated Mercer Arena in 1964 and moved to the larger Center Coliseum, which opened during the 1962 World’s Fair), the Totems swept Vancouver to win their second WHL title. They won the championship again in 1968, beating the hated Portland Buckaroos in five games.

When Fielder recalls his 15 years in Seattle (he lived in Edmonds, where he purchased his first and second homes, one of them a trailer), four things come to his mind: His teammates and the friendships, the Totems’ fierce rivalry with the Buckaroos, a galling playoff loss to the San Francisco Seals in 1963, and a playoff triumph over Portland in 1968, which still ranks as one of the most remarkable postseason victories by a Seattle team in any sport.

In the 1963 WHL finals, the Totems faced the San Francisco Seals (named in honor of the city’s former minor league baseball team), with all seven games at the Cow Palace due to scheduling conflicts at Civic Arena in Seattle. Seattle seemed to have a title locked, leading three games to one. But the Seals rallied to take the final three contests — two in overtime — and captured San Francisco’s first pro hockey title.

“Tough to lose, but I’ll never, ever forget that series,” said Fielder.

Five years later, in the finals against the Buckaroos, the Totems collected a victory in Game 1, but fell behind 6-2 after two periods of Game 2 at the Coliseum. Seattle then scored two goals in the first minute and a half of the third, and another about halfway through the period to slice the Buckaroos’ lead to 6-5. The Totems believed they scored the tying goal late in the period, but officials waved it off due to a high stick. With just over a minute to go, Seattle pulled its goaltender, and scored at 19 seconds. Fielder hit the game winner in overtime in what announcer Bill Schonley described as “the greatest comeback in Seattle hockey history.” The Totems won the series in five games.

“That’s one game I’ll just never forget, because of the rivalry,” said Fielder. “That was just an unbelievable game. I was fortunate.”

That marked the last time the Totems won a playoff series, and the end of good times for Fielder in Seattle. He was 39 and figured he didn’t have much ice time left.

“I got a little discouraged at the end of my career in Seattle,” Fielder explained. “I wondered what I was going to do with my life after hockey. Most places look after their players. I thought they (the Totems) would look after me. I went in to talk to them, and nothing happened, so I retired. I was a little disappointed in that respect. But we had some good hockey fans in Seattle.”

Fielder didn’t stay retired long, only a matter of months. He received a $20,000 offer from the WHL expansion Salt Lake Golden Eagles, coached by a former Americans teammate, Ray Kinasewich, who acquired Fielder’s rights from the Totems in exchange for Bobby Schmautz in 1969. Fielder spent two and a half years in the Utah capital before he was traded to Portland, where he finished his career (1972-73) and retired.

By that time, the Totems imploded. In 1971-72, they went a wretched 12-53-7, finishing with 17 fewer victories than the next-worst team. Those Totems scored 175 goals, lowest in league history, and allowed an astounding 331. Goaltender Jack Norris had a 5-28-5 record and allowed 4.14 goals per game. His backup, Bob Sneddon, went 3-13-2 and allowed 5.31. The Totems’ 53 defeats were the most in a single season in WHL history.

Worse than the mess on the ice: The Totems financial situation had become so dire that owners Vince Abbey and Eldred Barnes sold a majority interest in the club to Northwest Sports, which owned the Vancouver Canucks of the NHL, to keep their Seattle operation afloat. A condition of the sale permitted the Totems to survive as a farm team of the Canucks and included the proviso that if Seattle were ever offered an NHL franchise, Abbey and Barnes would be entitled to re-acquire the team from Northwest Sports.

The Totems enjoyed few highlights after that. On Dec. 25, 1973, they defeated a touring Czechoslovakia Army Team 6-4 in front of 6,041 at the Coliseum. Eleven days later, the Totems squared off against the Russian national team, also at the Coliseum, in a game that represented the coming out for a young Russian goaltender, Vladislav Tretiak, who would become an international star over the next decade. More than 12,700 fans watched the Totems, behind Don Westbrooke’s hat trick, score a shocking 8-4 victory over the defending world champions.

Seattle’s sporting fortunes took a turn for the better in 1974, when the city received a National Football League franchise (Seahawks) and a North American Soccer League franchise (Sounders). Although he had made no impact yet, Don James also signed to coach the University of Washington football team, and King County broke ground on the Kingdome.

One other development: On June 12, 1974, the National Hockey League announced that a group of Seattle businessmen, headed by Abbey, had been awarded an expansion team to begin play in 1976-77. Cost of the franchise: $6 million. The condition: Abbey had to make a $180,000 deposit on the franchise by the end of 1975, and had to repurchase the shares in the Totems he sold to Northwest Sports (Canucks) in 1972.

The announcement that Seattle, along with Denver, would receive an NHL franchise spelled the end of the Western Hockey League. In 1975-76, the Totems moved to the Central Hockey League.

The team never happened. Abbey missed several NHL-imposed payment deadlines while scrounging for financing. A desperate Abbey tried to pluck the Pittsburgh Penguins out of bankruptcy for $4.4 million in June 1975, and also attempted to lure the San Francisco franchise (California Golden Seals) to Seattle for the 1975-76 season. Both efforts failed. Eventually, the Seattle and Denver NHL expansion deals fell apart. Denver joined the new World Hockey Association, the money-losing Totems folded, Seattle wound up with nothing, and Abbey sued the NHL on anti-trust grounds. That went for naught: The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals finally tossed out his claim.

”I was really disappointed the Totems folded,” said Fielder. ”With the NHL and the new World Hockey Association, there just weren’t enough good players to keep our league going.”

Historically, Seattle has had high-level professional hockey in its time, starting with the Frank Foyston, Bernie Morris-led Metropolitans (Pacific Coast Hockey Association, 1915-24) and continuing with the Eskimos (Pacific Coast Hockey League, 1928-31), Sea Hawks (North West Hockey League, 1934-41), Ironmen (PCHL, 1944-51), Bombers (WHL, 1952-54), Americans (WHL, 1955-57) and Totems (WHL, 1958-69). But after the latter bellied up, Seattle did not receive another team until the junior-level Seattle Breakers (now Thunderbirds) were established in 1977.

The city seemed primed to receive an NHL team in 1990, when a consortium led by Chris Larson of Microsoft, former Totems player and coach MacFarland and Bill Ackerley, son of Sonics owner Barry Ackerley, met with league officials to discuss the matter. The Seattle bidders went to the expansion meetings prepared prepared to pay a $50 million expansion fee, but Barry Ackerley mysteriously (at least it seemed mysterious then) undercut his co-presenters by unilaterally informing the NHL that Seattle would withdraw its expansion application.

Turned out Ackerley did not want the Sonics competing for favorable Coliseum dates and advertising dollars with an NHL franchise. So when the Coliseum underwent a $100 million facelift in 1994-95 to become KeyArena, Ackerley had it designed so that it could not accommodate the bigger floor required for an NHL franchise.

Fielder settled in Portland after leaving hockey, bought a place on the Oregon coast and took a job no one could have anticipated.

“I worked at the dog track in Portland selling mutuel tickets,” Fielder said, “and then in the summers I worked at Turf Paradise (a race track in Phoenix). I did that for 15 years. I also had a house-watching (security) business for a couple of years – we watched 70-80 houses 24/7 – but eventually I got tired of the cold, wet winters and moved to Arizona.”

For a lot of years, golf served as Fielder’s principal competitive outlet. He played several times a week as a 5-handicapper, even into his 70s.

“I still play a little bit of golf, but mostly pool now,” he said. “I can’t make the little putts anymore. I have it in my mind that I can’t make them, and so I can’t. It gets very discouraging when you can’t make those putts. So now I play in a pool league. It’s a little money game.”

Fielder has been married to his second wife, Georgia, and lives in a gated community in Mesa. Now 87, he doesn’t travel much, except to Tortilla Flat, an old ghost town east of Mesa, where he enthralls guests with stories about gold in the nearby Superstition Mountains. Fielder also keeps in touch with teammates – he sees MacFarland once or twice a year – and still watches hockey, although the modern game is not quite to his liking.

“I watch hockey all the time,” he said. “But I don’t really enjoy it anymore. There are three things. First of all, hockey has been taken over by big, strong, fast guys, but they don’t have a brain in their heads. Nobody can backhand. There’s no finesse anymore, so it’s like watching paint dry. There’s nothing happening.

“On top of that, the contracts are just ridiculous. So I enjoy hockey, I just don’t like the style they play. A lot of these players are goons who just go out there to fight. There aren’t any playmakers. They telegraph every play. I’ve never seen so many goals scored in my life from the corner. We never scored goals like that.”

Golden Guyle would know. He scored 401 (Hockey Reference.com) of them and assisted on 1,398 others.

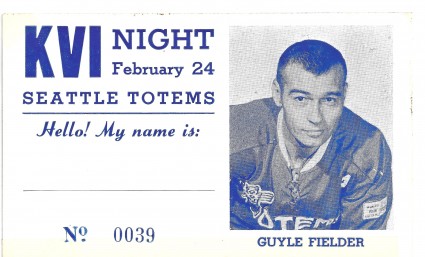

Lunch with Fielder At ShoWare Center

Not only is Guyle Fielder still going at 87, he’ll be in town.

Seattle’s greatest hockey player will sign copies of a biography, I Just Want To Play Hockey / Guyle Fielder, The Unknown Superstar by James Vantour Feb. 24 before the Seattle Thunderbirds game at ShoWare Center in Kent.

For fans who want more time with Fielder, a luncheon has been booked Feb. 23 from 11 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. at the arena’s Heritage Club. Tickets are $175, including lunch, a personalized autographed copy of the book and stories from Fielder’s time in Seattle sports from 1953 to 1969.

Also appearing will be Totems’ teammate Tommy McVie, who coached the Washington Capitals, the Winnipeg Jets and has been a Boston Bruins scout for the past 22 seasons.

Seating is limited to 14, and deadline for registration s Monday. Fans are welcome to bring other items to be autographed. For reservations or additional information contact Marc Blau at 253-677-2872 or at mhblau@comcast.net.

9 Comments

Great article on one of my favorite all-time Seattle sports figures!

Can’t wait for the NHL Totems!!!

Same suggestion for you Gary. Dine with your hero.

Seattle easily has the richest hockey history of any non-NHL American city, and Fielder is a big part of that. I hope the Thunderbirds, and even a possible NHL team, retires a number in his honor, because of his significance to Seattle hockey.

Good point, Kirkland. You should go have lunch with him Feb. 23 in Kent.

I remember the wretched 71-72 season. Royal Brougham promoted a Totem Turnaround Night. There were various give-a-ways and other promotions (including a skating Santa Claus) before the game and during the intermissions. If I recall correctly, the Totes did win that game. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of anyone else named Guyle.

Royal was either ahead of or behind the times. Never knew which.

He was one of the “ink stained wretches” when people cried, “Stop the presses,” and “Extra, extra, read all about it.”

Here is a thought and theory, Bonderman went to UW and I read that he went to allot of Totems games while as a student, I bet that will be the team name for the new NHL team and I would be all for that as long as it is okay with the local Native American community.

Good point. He has local roots, and likes to say he worked at the 1962 World’s Fair.But I expect there will be a lot of public input on the nickname.