At Washington Hall in Seattle’s Central District in September, a group called Historic Seattle hosted the ninth annual Preservation Awards Benefit. The event honors individuals and community groups that preserve and protect older Seattle buildings. That idea may seem incongruous to the reality of modern Seattle, where nearly every other block holds a construction crane.

But honoring and preserving historic structures is important for those who think a great city needs old, as well as new, buildings.

In attendance was a woman furiously scribbling notes about the passion of the award winners. The speakers talked about how old buildings had a soul, a history and great stories in the walls. She understood the feeling because she had fallen in love with a building.

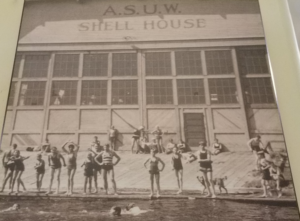

The object of Nicole Klein’s architectural affection is the ASUW Shell House (known today as the Canoe House). The barn-like structure is steps from the Montlake Cut on the southeastern tip of the University of Washington campus. For decades, it’s been used by alumni, faculty, students and staff as a storage area for personal kayaks, canoes and shells.

If buildings do indeed have a soul, if they do have a story to tell, pull up a chair on the eve of the 32nd annual Windermere Cup races Saturday on the Opening Day of boating season, and listen to this one.

The Canoe House was built by the U.S. Navy as a hangar for seaplanes made by Boeing that were to be used in World War I. The war ended before the building was deployed. In 1919, it was sold to UW for $1. Given what happened next, it might be one of the best real estate deals in campus history.

From 1919 to 1949 the ASUW Shell House was used as the training facility, storage area, locker room and construction shop for Washington’s internationally prominent rowing program. The building was a central character in Daniel James Brown’s The Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, the 2014 best-seller that captivated readers regardless of interest in rowing or any sport.

(Sidebar: Brown, the renovation plan and status of the feature film)

It’s where the legendary craftsman George Pocock designed and built boats that would carry UW rowers to victories around the world. Pocock’s shop was in a loft above the main floor of the building and the space remains today, reachable by a flight of stairs. It’s a piece of civic history that might have been forgotten had it not been for Brown’s astonishing chronicle.

“The building is a huge treasure,” Klein said during a tour. “It’s never been treated all that well. But it’s got good bones. We’re going to bring it back to its best heyday.”

Seattle native Bob Will was on the last Huskies rowing team to use the ASUW Shell House as a training center in 1949. Will, 93, rowed for coach Al Ulbrickson in boats designed by Pocock, a native of England. He remembers fondly the master builder of the eight-oared shells that were for decades sold around the world to premier universities, national teams and rowing clubs.

“He was generous with time, spirit and knowledge,” he said. “He would listen to anybody who wanted to ask a question and explain what he was doing while we watched him build boats.

“He was a wonderful, old-world gentleman. He was very philosophical and wasn’t afraid to give you his opinion on what you were doing wrong, either in rowing or in life. I got more out of him than any professor I had at UW.”

Will was a member of the U.S. fours boat that won a gold medal at the 1948 London Olympics. That win created so much excitement at UW that the school decided to build rowers a new home.

The Conibear Shell House opened in 1949 and was remodeled in 2005. In addition to Pocock, Will recalls the actual boys in the boat, the 1936 crew that made history.

“I was 11 in 1936,” he said, “and I remember the newspapers made a really big deal out of the UW rowing teams winning at the Olympics in Berlin.”

The time has come to honor the history at its birthplace.

Klein is the capital campaign manager for a project to repair, restore and upgrade the faded beauty. The idea to repurpose the Canoe House from its storage shed existence came three years ago when UW hired Matt Newman as director of recreation.

When Newman found out the building that starred in The Boys in the Boat was locked down with limited access — Brown had to sneak into the Canoe House when he was doing research for his book — he knew something had to be done.

“He kept saying that the building was too valuable to leave for so few people to see,” Klein said.

A series of campus meetings produced a re-imagination as an event space for receptions, parties, student activities and private gatherings.

Klein’s first job was to find a construction firm to inspect the 100-year-old structure to determine if the plan was even feasible — and be willing to do it pro bono. What happened next will draw envy and admiration from anyone who ever tried to sell anything.

She cold-called Hoffman Construction of Seattle and Portland, which had done work for campus buildings at Washington State and Gonzaga.

“I thought,” Klein said, “I was calling their community relations department and was prepared to give them a long pitch on the project.”

Instead, Klein reached executive vice-president Bart Eberwein. He read the book, so Klein had him barely after hello.

“The book was so strong,” said Eberwein. “It does what great books and art are supposed to do. It brings you together and makes you realize that we have a lot of common bonds. The sports thing, the hard-work thing, and the Northwest thing all teamed up. Our interest started with the book more than the building.”

After Klein gave him his first look, he was all in.

“The book and the building were a terrific one-two punch,” he said. “During my tour, I had the whole ‘if these walls could talk’ kind of thing going on. This is the place where Pocock made his boats and where the boys came to get their shells.”

Hoffman Construction did a three-dimensional scan of the building, inside and out as well as aerials. The report provided a list of repairs and upgrades. The work Hoffman provided would usually run into six figures, but Eberwein said the company was happy to help “get a little air under the wings” of what he called a unique project.

UW hired SHKS Architects of Seattle to begin the design phase, investigating what it will take to change an airplane hangar built in 1918 to a 21st-century multi-purpose events center. David Strauss, Ph.D., is the principal for the firm and also an adjunct professor at UW. Architecture students are contributing ideas.

“This building is as historic as anything at UW and many students have never even been down to this corner of campus,” Klein said. “Ultimately, we want it to be a space that students can use.”

The project has the enthusiastic support of UW men’s crew coach Michael Callahan.

“We consider ourselves one of Seattle’s teams,” he said. “We were here before professional sports. Crew has meant a lot to the Northwest for a long time. This new building will be a symbol of that. We can make it better, repurpose it, and maybe it will have another 100-year future.”

Creating a robust future won’t be easy. Updating to modern code an old building along a public waterway while preserving many original timbers and features will be a formidable challenge.

Architects and construction engineers relish that kind of challenge, according to Eberwein.

“This is much more challenging than if we were going to demolish it and construct a new building on the water,” he said. “The loftier goal of this project makes it very attractive to us.”

Fundraising will test Klein’s mettle over the next year. The project needs at least $10 million to complete. As with any major construction project, that number is likely to go up. She’s worked for UW as a fundraiser for various projects since 2006, but this will be different.

“It’s complicated because we will have to rely on a wide variety of donors, and there’s no set group to be targeted,” she said. “But it’s such a cherished building that we think it is possible we’ll get people involved who’ve never donated to UW before.”

Obviously, the city’s rowing community will be sought out. But Klein has seen evidence that interest is greater than that, thanks in part to a business developed by 2016 UW graduate and former rower Melanie Barstow.

A third-generation Husky, Barstow during her days as a student kept bumping into people sticking their heads into the Conibear Shell House a few hundred yards north of the old building and asking for directions to Pocock’s office. They all had one thing in common.

“They’d have a copy of Boys in the Boat with them,” Klein said. “Most of them have just randomly tried to find the building. People are finding it by chance. The other day there were three people from Maine who knocked on the door.”

Barstow had an idea — tours.

She was chagrined to find out that the only access was to those who stored boats there. She created an online petition demanding that it be opened for tours.

“Matt Newman didn’t know anything about Melanie,” Klein said. “But when he found out, he thought doing tours was a great idea.”

“Boys of 1936 Tours” was born. Barstow estimates she’s hosted more than 2,000 people over the past two years. Callahan loves the interest in the history.

“They want to see Joe Rantz’s gold medal,” Callahan said. “They want to see the 1936 Husky Clipper, and they want to see George Pocock’s shops where he built those boats. His legacy transcends our program.”

Klein is telling the tour story as she stands in the loft space where Pocock built the shells that revolutionized rowing in the 1930s. It’s the preservation of his legacy as much as the building that’s driving her to see this project through.

“Sometimes, people underestimate the power of George Pocock,” she said. “He put Seattle on the map for a lot of people and brought crew to another level. Treating what he did as a kind of language that we’re preserving excites me.

“This building does have a soul. It does tell a story. That’s our plan, to keep his workshop going. The same room, the same methods, the same smell of steamed cedar.”

Klein closes her eyes, breathes deeply, and sighs.

“It’s weird to be in love with a building.”

If the project is successful, the Seattle area will have a new/old building that will do in a physical sense what the book did in a literary sense — anchoring a place and a time where history was made and lives changed. It will embody the the city’s and the university’s legacy of rowing for generations, and build upon it.

“We teach our athletes about the history of the program,” Callahan said. “Pocock always talked to kids about building their own legacy. That’s still our mission.

“Know the past, but don’t live in it. Don’t miss the opportunity to build your own legacy.”

2 Comments

Gasman in the house! Good to see your mug.

I remember when Jim Nance touched your knee and said “that’s nice for you” when you told him you have (had) a radio show.

See if Jim Nance EVER gets a tour of the renovated shell house.