SPRINGFIELD, Mass. — For a town dead to the NBA, Seattle showed it could still light up the game.

The two most exuberant moments in the induction ceremonies for the class of 2019 at the Naismith Memorial National Basketball Hall of Fame were reserved for ex-Seattle SuperSonics star Jack Sikma.

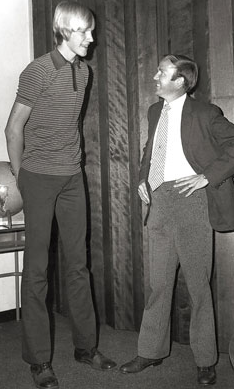

First, ahead of his speech, was a close-up photo of Sikma on a giant video screen on the day in 1977 he signed his rookie contract in Seattle. Beaming into the camera, Sikma’s blond hair was cut into straight bangs that nearly reached his eyebrows. The crowd erupted in shocked laughter.

Among the gigglers was one of Sikma’s presenters, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the leading scorer in NBA history.

“Kareem got a huge laugh out of it,” Sikma said at an after-party. “He came up to me and said, ‘I didn’t know you were in the Beatles.'”

The second moment came a few minutes into Sikma’s speech when he thanked family and friends who traveled from his home area in rural Illinois, from his adopted home town in Seattle, and Milwaukee, where he spent his final NBA years.

” . . .and there are a few of you here . . .”

The Symphony Hall erupted in cheers, shouts and whistles at the acknowledgement. It was easily the largest and loudest collection of fans for any of the 12 inductees. It seemed a bit like a Seahawks road game, where traveling 12s often out-shout the home crowd.

No one in the grand old building in the town where the sport was born was prouder in that moment than a little white-haired man a few rows back from the stage who was primarily responsible for Sikma’s advance into hoops Valhalla.

Not only did Dennie Bridges recruit Sikma to tiny Illinois Wesleyan when he had scholarship offers from from big-time programs such as Illinois, Purdue and Kansas State, he helped teach Sikma his signature, reverse-pivot move.

Then long after the end of Sikma’s 14-year NBA career, which included a championship and seven All-Star Game appearances, Bridges began a more arduous task — getting the attention of the anonymous, mysterious Naismith Hall voters to the facts of Sikma’s worthiness for inclusion.

“It was hard,” said Bridges. “But we did it. And here we are. To see him on that stage, with so many great players . . . ”

Bridges paused and looked back up to the stage where Sikma and the greats were mingling, laughing and hugging, post-event. Bridges was wet-eyed and beaming.

” . . . Fantastic.”

He paused again.

“I told the university president that I was recruiting this guy who I was sure would become the greatest scorer in Illinois Wesleyan history,” he said. “I didn’t see this.”

On that spring day in 1977 when Sonics coach Lenny Wilkens shocked the town by selecting the little-known Sikma with the draft’s eighth overall pick, Bridges recalled a phone conversation with a Seattle reporter looking for background information.

“I said, ‘Just give him a year,'” said Bridges, urging patience.

Patience is a signal virtue in farm country, where crops must be grown and chores done with a view to the literal and figurative far horizon. Nothing spoke to the mastery of patience more readily during the evening than the fact that it took Sikma 28 years following his retirement to reach this moment.

And Seattle sports fans were torqued that baseball took 15 years after Edgar Martinez retired to recognize he belonged.

“I started maybe 10 or 15 years ago,” Bridges said of his campaign to at least get Sikma nominated. He was directed to several basketball industry people, most of whom were dismissive of Sikma’s chances.

Finally he reached someone close to Jerry Colangelo, the former owner of the Phoenix Suns, who remains the unofficial don of global basketball. Apparently, there was a supportive wave of the hand from Colangelo, who knew Sikma well from the days when his Suns and the Sonics were Pacific Division rivals. A stir began.

Enlisted was Wayne Embry, a Hall of Famer as a player and a longtime team and league executive, who was working with Sikma in Toronto, where he was a part-time consultant helping the Raptors’ big men. Wally Walker, a title-squad teammate and longtime friend who was a former Sonics president, began working his connections. The increasing use of analytics uncovered impressive comparatives with Hall of Famers, much as what happened with Martinez’s ascendancy among baseball writers.

One call after one text after one email, momentum built. Sikma was nominated in February by a committee, which passed up his name to an 24-person honors committee, whose identities remain a public secret, and rotate every three years. Sikma drew votes from at least 18, and his ordination was officially announced at the NCAA Final Four in April.

The laborious process was not unlike what Bridges put Sikma through when they improved Sikma’s offense with the inside-pivot move and an overhead release that became his trademark. The mastery of its multiple non-instinctive moves required constant repetition. And patience.

“After practice was over, Jack would stay and shoot it 100 times from the left side, then 100 times from the right side,” Bridges said. “It took that kind of work so he got used to it and never had to think about it.”

A payoff for Bridges came Saturday night.

“Dennie was committed to a late-blooming, 6-11, 195-pound specimen,” Sikma said during his speech. “The inside pivot fit my body type and shooting skills. I still hear the coach from the sidelines: ‘Do your move!’ ‘Do your move!’

“Thanks for your move, and more importantly, your life-long friendship.”

Bridges handed off Sikma to Wilkens, who knew he had a player motivated to make it in the NBA.

Sikma had been invited to the 1976 Olympic Trials, but failed to make the team in part because U.S. coach Dean Smith kept four players from his day job at the University of North Carolina: Mitch Kupchak, Phil Ford, Walter Davis and Tom LaGarde, a future Sonics center.

“Jack was really disappointed,” Said Bridges. “He came back from the trials and said, ‘I can play with those guys.'”

The ultimate validation of that observation came Saturday night.

Sikma didn’t miss a chance to offer a well-received acknowledgement for the ongoing hoops heartache in Seattle. With former commissioner David Stern, who wielded the ax on Seattle’s NBA tenure, along with his successor, Adam Silver, in the audience, Sikma offered up a carefully worded plea.

“Thanks to all the die-hard Sonics fans who supported the green and gold — it was a thrill to play in front of you,” he said. “There’s a hole in Seattle that needs to filled. Speaking for all Sonics fans, our greatest hope is the NBA will soon find a pathway to bring the Sonics franchise back to Seattle.”

The well-paced evening was filled with surprising histories and poignant words from grateful recipients of the game’s highest honor, saluting basketball’s positive influence on matters of family, race, gender and globalism. Particularly riveting was the passionate expression of WNBA star Teresa Witherspoon, found here.

For the Seattle fans in the crowd, the night was a sentimental flashback to a bygone sports era.

From his rookie year in 1977, Sikma recalled the talk Wilkens gave after he took over the Sonics following a 5-17 seasonal start.

“Lenny said we could win with this group,” he said. “We were 5-17. Really?”

Really. Forty-two years later in Springfield and 11 years after the show closed in Seattle, Wilkens’ preposterous yet accurate optimism had a long-delayed encore finish.

11 Comments

If Jack was on the 1976 Olympics Men’s Basketball team at the very least he’d have received a significant amount of playing time. Even though all members of the team made the NBA and had perennial All-Stars such as Walter Davis and Adrian Dantley none had a game that could compare to Jack’s, especially as a rebounder and none have been named to the HOF. He really should have been on that team.

It’s been said before, the HOF system for nominating prospective members needs to be overhauled. Except for Weatherspoon and Divac all of the 2019 class should have been named long ago. It’s a shame Chuck Cooper didn’t live to see this day.

Adrian Dantley IS in The Hall of Fame – The Class of 2008

You’re right. My mistake.

Jack will be pleased that you’re in his corner. In fairness, Jack in 78 and 79 was more physically mature than in 76.

I used to think the system needs changing, but it has seven committees scanning for candidates around the globe. The heavy use of analytics creates a knowledge base that allows the Hall to play catch-up regarding the overlooked.

My dad (in his early 70’s) and I were talking basketball just the other day when he brought Sikma’s name up and said he’s in the HoF. I told him he was wrong. I honestly had no idea #43 had been voted in until I looked it up later that night. Ironically, Bobby Jones’s name also came up in that same conversation. Hadn’t heard/read about him going in, either. Same for Moncrief and Westphal. I’m genuinely surprised the old guard are even being considered. I gave up once they voted Tracy McGrady in. It was made abundantly clear at that point that the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame had no interest in being taken seriously anymore.

As the column says, it takes a village sometimes to make a case, especially when a franchise no longer exists in the NBA. The fact that his candidacy overcame that void says much about the quality of the rationale behind his nomination.

Glad to hear your dad is still smarter than you.

Next up—- a campaign for Downtown Fred Brown.

Nice idea, but I don’t think that will work. Too bad the bulk of his career was before the 3-pt line.

The Sonics’ first star center, Bob Rule, died last Thursday. May the Golden One R.I.P.

Rest in Peace Bobby Frank Rule – https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/7fc378209375cbffd40f652ca7008ef89bb79281480627f366733921e64316c4.jpg

Thanks for posting.