It’s as if the NCAA Tuesday leaped away from the buggy, slapped the horse on the hindquarters and jumped into a 1965 Mustang convertible.

How long it will take for the reform-resistant cartel to buy the 2020 Tesla remains unknown. But at least the business of college sports has made it to pavement, and reaching the 21st century will happen more quickly.

Meeting in Atlanta Tuesday, the NCAA’s board of governors, shivering in the shadow of the California state legislature and potentially a dozen other like-minded states, released a statement saying it was beginning a process with its member schools to modify rules to allow college athletes, by 2021, to profit from their names, images and likenesses.

The vote on the policy change was unanimous.

Ta-dah.

To underscore the moment in college sports history, ta-frickin-dah.

Finally, college athletes are in for a slice of the financial action they’ve been denied for more than a century: Instead of under it, being paid over the table for their labors that enrich their schools.

But then the poohbahs threw in a slippery slope of a qualifier: ” . . . in a manner consistent with the collegiate model.”

What that is, isn’t entirely clear. But I think they seek to reach a human frontier previously deemed unreachable: A little bit pregnant.

Forced to accept professionalizing college sports, the NCAA seeks to call it something else. Puppy dogs, artichokes, gargoyles, anything but what it is, and always has been — pro sports, albeit with free labor, at least until January 2021.

In the letter, the NCAA outlines the mandate for all three divisions of competition:

- Assure athletes have the same chance to make money as all other students

- Maintain the “priorities of education and the collegiate experience”

- Ensure rules and transparent, focused and enforceable

- Ensure competitive balance

How all of that is going to work, I have no idea. Especially with the highest-paid employee in 39 of the 50 states, the football coach, screaming in the collective ears of presidents and athletics directors, “Do you know how much this sucks!?”

Doesn’t matter. Enlightenment 1, Injustice 0. No replay review. No challenge flag.

“We must embrace change to provide the best possible experience for college athletes,” board chair Micheal Drake, president of Ohio State University, said. “Additional flexibility in this area can and must continue to support college sports as a part of higher education. This modernization for the future is a natural extension of the numerous steps NCAA members have taken in recent years to improve support for student-athletes, including full cost of attendance and guaranteed scholarships.”

The change came after a working group of administrators, assembled in May, put forward its recommendations to the board. At almost the same time, the California state assembly worked on a bill denying the NCAA the right to punish schools in the state that permit college athletes to receive compensation for use of their likenesses.

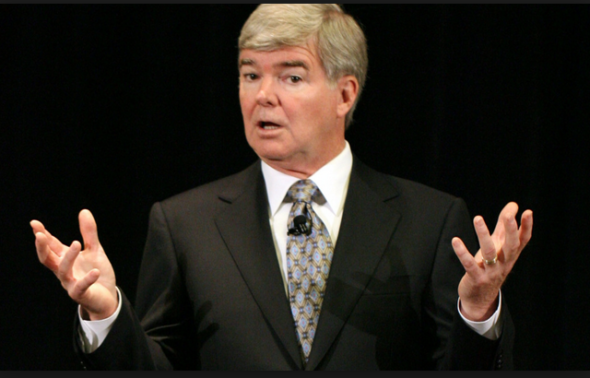

Despite the pleadings of NCAA president Mark Emmert, the former University of Washington president, who claimed the law was unconstitutional, the California bill was signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom in September.

The law wouldn’t be implemented until 2023, giving the NCAA time to begin doing what it started Tuesday — cave.

The law represented the most successful legislative incursion into the fiefdom of the NCAA, which for years had cajoled a majority in Congress to look the other way while it propped up amateurism as a legitimate basis upon which to operate its hugely successful entertainment division. As well as to provide game tickets on Saturday to the electeds’ entourages.

The chief virtue of the change for the schools is that it requires no re-directing of athletics revenues to players. That may come someday, but for now, it’s outside money coming from sponsors and businesses who seek players for endorsements.

The chief liability is that it will be exceedingly difficult to make the new method an even playing field.

Not only will its impact likely be felt by just a few athletes per school — it’s hard to imagine five athletes at UW who have a brand sufficient to attract a market, unless a sponsor wants to give the softball team or the football team $1,000 per player — some marketplaces are going to be better than others.

USC and UCLA have the world’s largest entertainment companies in their front yards. In Seattle, Microsoft, Nintendo and other video-game makers could shower cash on collegians to spread the brands. But in Pullman, Corvallis, Omaha and Lubbock, it’s hard to say what companies might offer a big-city kid to show up in a small town. A John Deere tractor?

Last year, a kicker at UCF gave up his scholarship rather than stop making money off his profitable YouTube channel, which was a threat to his eligibility. But Notre Dame basketball star Arike Ogunbowale was allowed to participate in the show Dancing With the Stars.

Whatever shape this reform takes, it’s overdue, significant, fascinating and urgent — members of the football recruiting class of 2020 can start making money by their sophomore seasons.

Imagine a place where a disgraced airplane shop feels compelled to buy its way back into civic graces . . .

15 Comments

Will this be prorated to the older days? I may have some skin in the game.

I think the statute of limitations has run out on you.

Indeed.

This reminds me of how the pro sports leagues adamantly opposed expanding sports betting outside of Nevada, but then immediately announced partnerships with casinos and sports books right after the Supreme Court legalized it.

And now here comes a twist: A senator is proposing to tax the earnings the athletes would get from this law: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/29/richard-burr-proposes-taxing-scholarships-of-student-athletes-who-cash-in.html

A fair analogy. Pro sports were attempting to take a high moral road against the industry that birthed their phenomenal growth. Then when the courts declared the wall irrelevant, they jumped in hard, so as not to get left behind.

Same will happen with the NCAA.

I’ll be curious to see how this impacts the non-revenue sports.

See answers above.

Two points 1. How is title IX going to impact this and 2. In only two sports will this affect collegiate athletes

Title IX is not relevant here because it is already in place to make sure in-house department resources are distributed equally regardless of gender. And while football and men’s hoops are the only likely beneficiaries now, we can’t know how sponsorships will look in the future. Maybe a high-end clothier wants to support each member of the volleyball team.

“The chief liability is that it will be exceedingly difficult to make the new method an even playing field.”

What is important to focus on here is that a laudable principle is being established, not that its first manifestation is flawed. A crack has finally appeared in the previously solid wall of college amateur athletic bondage. Once established and accepted, it will surely expand.

As Art points out, the right of athletes to share in the profits derived from the marketing of their images and names only benefits a few celebrity athletes in major media markets and in the short run could operate to make the disparity between the NCAA haves and have-nots even more glaring. It is no accident that this breakthrough occurred in the great State of Hollywood. But image theft represents a particularly egregious form of unfairness, so it offered an obvious starting place. The challenge will be to expand in a broad and equitable way the principle that sports workers should be justly compensated for labor that financially enriches their academic employers.

It won’t be easy. Currently, the field hockey, football and cross-country teams all operate within the same basic regulatory framework, one designed with the true amateurs in mind. Maybe a division between major revenue generating sports and the lesser forms will be part of the answer. Who knows? The only two things really clear at this point are that a historic barrier has fallen, and that it will require someone more courageous and principled than Mark Emmert to figure out how to make the new system work.

Well said, woofer. Reform, like anything else, has to have a first step. Subsequent steps in this case is going to be chaotic, particularly for the non-rev sports who will be marginalized.

My hope? Non-rev teams each get single corporate sponsors who can pay each team member $1K/mo, in exchange for signage and public appearance(s). We all resent the billboard culture, but knowing college kids are getting survival income makes it bearable.

There seems to be a lot of ways the NCAA could chop down on the effectiveness of this ruling. Sports law professor Michael McCann has a quite detailed analysis of what legal questions need to be answered: https://www.si.com/college/2019/10/30/ncaa-name-image-likeness-announcement-takeaways-questions

At the very least, I’d like to see athletes get unlimited meal cards; I hear finding enough food in the off-season is an issue, and nutrition has to be paramount for an athlete. A decent stipend like that of junior hockey players would also help.

The picture of Mark Emmert immediately took me to Alfred E Neuman. “What, me worry?”.

Just go the whole way and make Division I the minor-leagues of their respective pro sports because that’s what they’ll be once this goes into effect. Soon recruiting efforts will include a modelling contract and athletic gear endorsement packages.

Sally Jenkins in WaPo had an interesting commentary about this- her take, this is a smokescreen continuing as always. A few stars in football and b-ball will benefit as will a smaller number in the non-revenue sports. But the majority in the revenue sports will work to continue to pad the salaries of the coaches and administration. Used and spit out.