Wow. Who knew that Jarred Kelenic would be washed up after just 23 games in the major leagues?

We jest, of course. Still, the reaction of some Mariners fans to Kelenic’s failure to immediately light up the baseball world at 21 seems a bit overboard.

Granted, Kelenic’s .096 batting average was pitiful. Hitless in his final 39 at bats, he returned to AAA Tacoma this week in desperate need of a boost in his stats and confidence.

“Sometimes, you just need to help them slow it down, and this is all that is with Jarred,” Dipoto told reporters. “We don’t think he’s overwhelmed by the level of play.

“We believe he’ll succeed. He’s just not doing that right now.”

Although Kelenic is one of baseball’s top prospects, the young outfielder is proof that it is exceedingly difficult to hit a thrown baseball in the major leagues. It also is exceedingly difficult to pitch in the major leagues.

As proof, we look back on the painfully slow career starts, for a variety of reasons, of 10 Hall of Fame players, all of whom had a tie or two to the Pacific Northwest.

Edgar Martinez

The ex-Mariner is regarded as one of the finest right-handed hitters in history. No one would have predicted that in 1983, when Martinez batted .173 with just two extra-base hits (no homers) in 32 games as a rookie pro with Bellingham in the short-season Class A Northwest League.

Martinez was 27 and in his eighth season of pro ball before he played a full season in the majors. He retired as one of six players in major league history with career marks of 300 or more homers, 500 or more doubles, a batting average of .300 or higher, an on-base percentage of .400 or higher and a slugging percentage of .500 or higher.

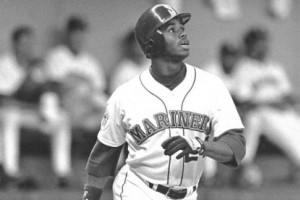

Ken Griffey Jr.

The greatest player in Mariners history hit .189 in his first 14 games in the majors, when Seattle rushed the 19-year-old center fielder to the bigs less than two full years after he graduated from high school.

Griffey went 13-for-20 (.650) over his next five games to lift his average to .333. He tailed off late in the season, but still posted respectable rookie numbers with a .264 average, 16 homers and 61 RBIs in 127 games. Griffey ended his 22-year career with a .284 average and 630 home runs (seventh all-time).

Sandy Koufax

Midway through his career, Koufax found himself at a crossroads. The southpaw struggled to throw his mighty fastball for strikes and had a mediocre 36-40 record with a 4.10 earned run average after six seasons with the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers.

Koufax’s fortunes turned around in 1961 after journeyman Dodgers catcher Norm Sherry, a former Spokane Indians player, convinced Koufax to stop trying to throw as hard as possible.

The result was one of the greatest six-year stretches in history from 1961-66: A 130-47 record, 2.19 ERA, 115 complete games, 35 shutouts, six All-Star Game selections and three Cy Young awards as the National League’s best pitcher. In 1966, an elbow injury forced Koufax into retirement after he led the NL with 27 wins, a 1.73 ERA, 323 innings pitched, 27 complete games, five shutouts and 317 strikeouts.

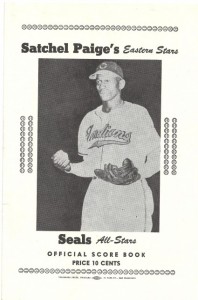

Satchel Paige

One of the saddest truths about American sports is that thousands of worthy Black players were denied the opportunity to play in the major leagues until Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1947.

Paige did not make his big league debut until he was 42, more than two decades after he began playing on Black pro teams. Once he made it to the bigs, Paige posted a 6-1 record and 2.48 ERA as, officially, a rookie, while helping the Cleveland Indians capture the 1948 American League pennant. Paige was 54 when he pitched in five games with the PCL’s Portland Beavers, and he was 59 when he tossed three innings of one-hit, shutout ball for the Kansas City (now Oakland) Athletics in his final major league game in 1959.

Walter Johnson

It was bad enough that Johnson was cut by the Tacoma Tigers during his first pro tryout in 1906. Making matters worse was the fact that Tacoma player-manager Mike Lynch told the side-armer he should give up pitching to become an outfielder.

Two years later, after the Washington Senators signed Johnson off a semipro team in Weiser, Idaho, Johnson began a spectacular 21-year major league career. Nearly a century after he retired, Johnson still lays claim to all-time rankings of first in shutouts (110), second in wins (417), third in innings pitched (5,914 innings), fifth in complete games (531), ninth in strikeouts (3,509) and 12th in ERA (2.17).

Hoyt Wilhelm

The knuckleballing relief pitcher spent seven years in the minors and three more years in the military during World War II before he finally reached the majors. As a 29-year-old rookie, Wilhelm rewarded the 1952 New York Giants by going 15-3 and leading the National League with a 2.43 ERA, 71 games pitched and an .833 winning percentage.

Only five players in major league history have pitched in more games than Wilhelm (1,070). He was nearing his 50th birthday when he wrapped up his 21-year major league career in 1972, one year after he appeared in eight games with Spokane in the PCL.

Randy Johnson

Few people in baseball questioned Johnson’s potential as a young pitcher. Fortunately for the Mariners, some of the doubters worked in the Montreal Expos’ front office, so the Expos traded Johnson to Seattle in 1989.

Johnson blossomed into one of the game’s finest pitchers, once a few tips from legendary pitcher Nolan Ryan helped the 6-foot-10 Johnson learn to control his blazing fastball. Johnson led the American League in bases on balls during each of his first three full seasons with Seattle, but he later won four straight Cy Young awards with the National League’s Arizona Diamondbacks (in addition to one with Seattle in 1995). Only Ryan struck out more major league batters than Johnson (4,875).

Mike Schmidt

The legendary boo-birds of Philadelphia had a field day with Schmidt in 1973, when the highly touted third baseman hit just .196 in his first full season with the Phillies. Schmidt slugged 18 home runs, but he struck out a National League-leading 136 times for an average of one whiff for every 2.7 at bats.

One year later, and two years removed from a banner season with the PCL’s Eugene Emeralds, Schmidt began flashing his Hall of Fame form by hitting .282 with 36 homers and 116 RBIs. Schmidt spent his entire big league career in Philadelphia, where he won three Most Valuable Player awards and 10 Gold Gloves. His 548 career homers rank 16th all-time.

Joe McGinnity

McGinnity’s career was a remarkable one. He pitched in the minors until he was 54 years old, 17 years after he last pitched in the majors. He averaged 24 wins per season in the majors, but he also averaged 344 innings pitched, which helped limit his major league career to 10 seasons.

Nicknamed “Iron Man,” McGinnity spent three years playing semipro and amateur ball after he was released following two losing seasons to start his pro career. One year after returning to the minors in 1898, McGinnity won 28 games as a 28-year-old rookie in the majors. His career peaked in 1903-04 with the New York Giants, when he won 66 games (31 and 35, respectively) and pitched a stunning 842 innings (434 and 408, respectively). McGinnity won 41 games with Tacoma in 1914-15.

Earl Averill

The Snohomish native briefly gave up baseball as a teenager due to arm trouble, then bounced around on various semipro and “town teams” until he turned pro at 23 with Bellingham. He was nearly 27 when he reached the majors and hit .332 with 18 homers and 96 RBIs for the 1929 Cleveland Indians.

Averill, a fleet-footed center fielder, hit over .300 in each of his first six seasons with Cleveland. During that span, he averaged 115 RBIs, 24 homers, 39 doubles and 11 triples. Averill was named to the American League team for the first six All-Star Games (1933-38). He retired after spending part of the 1941 season with the PCL’s Seattle Rainiers.

Howie Stalwick covered baseball and other sports for SportspressNW and dozens of news outlets nationwide (often as a freelancer) before retiring in his hometown of Spokane in 2016. howiestalwick@frontier.com.

14 Comments

Outstanding research. Well done!

Mr. Stalwick loves his ball research.

Mays went 1 for 25 when called up to the NY Giants. So you never know.

The box scores are filled with dead careers come to life.

As I recall, Nolan Ryan didn’t exactly set MLB on fire during his first few years in the bigs. He settled down, and became the HOFer that he earned and well deserved. Wisdom passed on to the Big Unit helped them both get to Cooperstown. Kudos to all who struggled along the way. They, like us, are only human..

The story I heard was that Ryan and his Rangers’ pitching coach Tom House noticed that the young Johnson wasn’t pointing his plant foot consistently, which caused his wildness. So between games of a Rangers-M’s series, the three got together to train Johnson to point his plant foot in exactly the same direction/angle. After that mound session, there was no turning back for Johnson.

My only question is, why was it the opposition’s pitching coach noticing this and not the M’s?

That’s how I heard it.

The story of the new team finding and fixing the new player’s old flaw is an old one in baseball. Happens all the time, but less now because of the use of video and data helps detect mechanical flaws in pitching and hitting much more readily.

Because it’s the hardest sport to master, pitching and hitting, it has the highest failure rate, made worse because the 30 clubs have fixed roster space that can tolerate patience in only a select few per year. Players run out of time and need to get jobs.

I remember watching with my father a replay of a 1969 World Series game, when a rookie Nolan Ryan entered for the Mets in relief. Broadcaster Lindsay Nielsen said, ” Everybody knows young Ryan has a great fastball; the idea is to get him to develop a breaking ball to complement that fastball.” Dad and I looked at each other and burst out laughing.

How wise were you and Dad. Nelson, what did he know?

Great article. Great walk down Memory Lane. But a couple of points. Stories about pitchers who fail early then succeed later aren’t truly relevant to whether a young hitter is likely to emulate that success. When a mediocre pitcher has a sudden breakout it’s usually because he has mastered a really effective new pitch that nobody can get good wood on. My favorite example of that is the late, great Calvin Coolidge Julius Caesar Tuskahoma McLish. Cal, as his more intimate friends used to call him, never had a big league winning record in seven seasons between 1944 and 1957, nor an ERA under 4.00. Then suddenly he had three consecutive winning seasons in Cleveland, two with an ERA under 3.00 and topping out with a 19-8 record in 1959. As Cal himself once sort of explained it, late in life he developed a sort of a changeup screwball.

The other point is that Triple A ball has become a fraudulent category. The PCL is more like High Double A. The gap between the pitching talent a young hitter sees in Tacoma and what he sees in Seattle is vast. Back in the old days before the Dodgers and Giants came west in their wagon trains to lead the invasion, the quality of talent in the PCL was just a notch below the majors. No more. The PCL may sometimes be regarded as better than it actually is because it still is able to cruise a little on its ancient reputation.

So, young tyro Kelenic had to make a big jump and didn’t quite leap across the chasm on his first try. Good thing he has a nice big ego to prop him up. He should be all right. And a fella kinda gets the impression that Mr Dipoto thinks Kelenic’s recent experience might even do him some good.

Fair point that pitching development can be different than hitting, but the broader point about the rarity of instant MLB success is valid.

The “old days” of 1950s MLB/PCL ball is so different than today’s game that comparisons are irrelevant on many levels. Four obvious points of distinction: MLB clubs were far fewer, Black/Latino players were far fewer, hitters often weren’t as fit as they are now also face defensive shifts.