Hockey’s most storied franchise, the Montreal Canadiens, visited the Pacific Northwest in October for their first professional game on Seattle ice in 102 years.

To commemorate the occasion, the Kraken unveiled the Seattle Metropolitans’ 1917 Stanley Cup championship banner, won when the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) Metropolitans defeated the National Hockey Association’s (NHA) Montreal Canadiens. The victory made Seattle the first American city to win the vaunted Cup.

Two years later, at the tail end of the Spanish Flu global pandemic, the National Hockey League’s Montreal Canadiens returned to Seattle for the 1919 Stanley Cup Final. The series was canceled when five Canadiens fell ill the morning of the deciding game six, marking the only championship tie in North American professional sports annals.

First American team to win the Cup? Only championship tie in major North American professional sports? Heady historical stuff. Yet, only the most visible components of Cascadia’s deep history and lasting imprint on hockey.

Equally intriguing is how the Metropolitans played the NHA’s Montreal Canadiens in 1917 but the NHL’s Montreal Canadiens in 1919. Or, more importantly how the PCHA and NHA fit together to form the Original Six that shaped the present-day NHL.

PCHA influence of today’s NHL

The PCHA was founded by a pair of hockey Hall of Fame brothers, Lester and Frank Patrick, with the younger Frank serving as PCHA president.

According to the Hockey Hall of Fame, Frank Patrick is “the brains of modern hockey.” More than 20 PCHA rules remain in the NHL today, including the blue line, forward pass, playoff system, awarding assists, penalty shot, kicking the puck (except into the net) and allowing goalies stop pucks any way they saw fit, rather than forcing them to remain on their feet. A shrewd businessman, Frank was also one of the first to assign player numbers so the league could sell programs to fans.

Similar to football’s AFL and NFL of the 1960s, the PCHA began as a competitor to the NHA, though soon became a complementary league. Between 1915-1926, the winner of each circuit played a five-game series for the Stanley Cup, even then the “greatest of all hockey trophies.”

When the PCHA expanded to Portland and Seattle, rumors flew that neither American team could claim the Cup. Lord Stanley’s trustees quickly put that to rest, stating, “the Stanley Cup is not emblematic of Canadian honors but of the hockey championship of the world.”

The east won eight of the 12 meetings for seven seasons at the height of the rivalry — 1916 through 1922 — going to a series-deciding fifth game six times. The only exception was the 3-1 trouncing of Montreal in 1917 by the Mets.

Similar to baseball’s American and National leagues, the NHA/NHL and PCHA played by some different rules. The east coast circuit played six-man hockey while the west played seven. Despite the west playing with an extra player, the PCHA’s team-based game is still played today while the NHA’s individualist style is not.

Formation of NHL

In November 1917, the NHA had five teams – Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Ottawa Senators, Quebec Bulldogs and Toronto Blueshirts. The Toronto franchise was owned by Eddie Livingstone. Caustic, petulant and hated in hockey circles, NHA leadership had spent the previous summer pressuring Livingstone to sell his franchise.

In the league meeting, held Nov. 12 at the Windsor Hotel in Montreal, the NHA decided to cease operations for the 1917-18 season. In the press announcement, it was reported there “was no change in the Toronto club situation, that the club remains the property of Eddie Livingstone . . . and that if the association operated, the Toronto club intended to remain as a member with equal rights.”

Twelve days later, representatives from the Canadiens, Wanderers, Senators and Bulldogs met at the same hotel. They “decided to start over” and form the “National Hockey League,” selling a new Toronto franchise to the Toronto Arena Co. According to the NHL, “the new league adopted the NHA’s playing rules and used its 25-page constitution as its governing document.”

With a lack of players due to World War I, Quebec decided not to play that season. The original four NHL teams then were the Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Ottawa Senators, and Toronto Arenas. Apart from a new owner in Toronto, the clubs had the same leadership, rosters and uniforms as the previous season, meaning the NHA champion Montreal Canadiens the Mets faced in 1917 was the exact franchise they faced as the NHL champion in 1919.

PCHA spawns Original Six

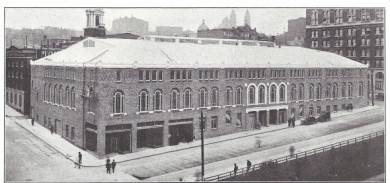

In a tale that would repeat itself nearly a century later in Seattle, the Metropolitans’ demise began when they lost their arena lease. The University of Washington, owners of the downtown Seattle Ice Arena, bought out the final year of the lease from the cash-strapped Patricks. The almost-finished Olympic Hotel across the street needed a parking garage and the arena was to be retrofitted for $150,000.

In late February 1924, as the Metropolitans secured their fifth and final PCHA regular season title, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer broke the story that the Metropolitans would “be homeless at the end month…as (the) arena cannot be used for playoffs.” Not surprisingly, the Metropolitans lost in the PCHA playoffs to Vancouver on the road.

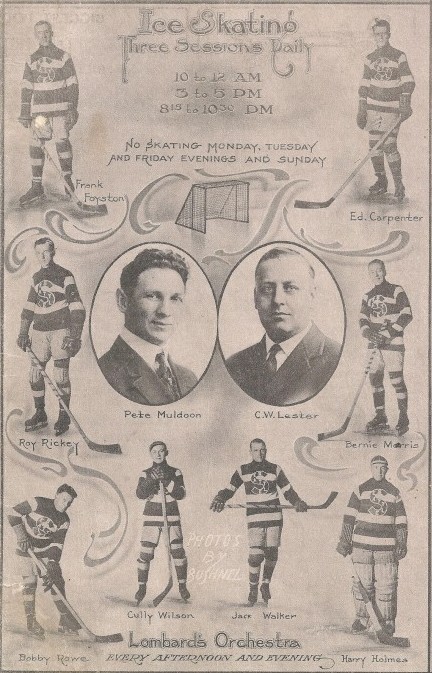

Unable to secure a new arena by the beginning of the 1924-25 season, the Metropolitans disbanded. Head coach Pete Muldoon moved to manage the Portland Rosebuds. The team’s core signed with Lester Patrick’s Victoria franchise, where they competed in the last two east/west Stanley Cup Finals, winning in 1925.

In the summer of 1926, major league hockey on the west coast ended and the NHL took sole possession of the Stanley Cup. Vancouver ceased operations while the Victoria and Portland clubs relocated east and joined the NHL, becoming two of the NHL’s Original Six – the teams that comprised the league from 1942 until the NHL expanded in 1967.

Victoria moved to Detroit, soon to be renamed the Redwings. Portland moved to Chicago and rebranded as the Blackhawks. Pete Muldoon remained with the franchise and became the first head coach.

Former Mets stars quickly littered NHL rosters: Jim Riley and Cully Wilson played on the inaugural Blackhawks team, while Bernie Morris and Bobby Rowe played for the expansion Boston Bruins. The Mets’ three Hall of Famers — Frank Foyston, Jack Walker and Harry “Hap” Holmes — graced the newly minted Detroit roster.

Lester Patrick moved to New York and became the longtime Rangers head coach, his 1928 squad becoming the second American team to win the Cup. A few years later, Frank Patrick was named managing director of the NHL. Seattle resident and head PCHA referee Mickey Ion likewise moved east to officiate in the NHL before becoming referee-in-chief in 1941. He was inducted in the first Hockey Hall of Fame class for officials in 1961.

In an era that predates radio and television, the PCHA’s story and influence have largely been relegated to the microfilm of yesteryear’s newspapers. For the Metropolitans’ inaugural contest, Post-Intelligencer sportswriter Royal Brougham quipped, “As usual, the management predicts a well-played game, but Seattle will not be able to tell whether the game is well played or not for . . . ninety-nine out of every hundred persons at the Arena will see the opening of their first hockey game.”

Much has changed for both Seattle and hockey since Mayor Hiram Gill dropped that first puck, making Seattle a major league city.

While the NHL doesn’t recognize PCHA records, you’ll see its influence all over the ice when you cheer on the Kraken, and boo Sunday night the Toronto Arenas, the visiting Original Six franchise that became Maple Leafs in 1927.

Pacific Northwest roots run deep in the NHL.

A former University of Washington baseball captain, Kevin Ticen’s 2019 book, When It Mattered Most, chronicled the Seattle Metropolitans’ historic 1917 Stanley Cup championship.