What remains of the sports world that doesn’t know much about Cooper Kupp likely will be filled in Sunday. The Super Bowl match in Los Angeles against the Cincinnati Bengals provides the biggest stage in sports, and the Rams are eager to feed the beast they helped create.

On a Sofi Stadium field full of premier players, Kupp is the most unstoppable.

Even Aaron Donald can be negated with enough blockers. But the kid from Yakima, one of five unanimous selections to the Associated Press All-Pro team, is going to get his, no matter the deployment, weaponry or strategy against him.

Despite the NFL universe knowing the Rams are intensely committed to getting the ball to Kupp, he still was the first wide receiver since Steve Smith in 2005 and fourth overall to lead the NFL in the top three categories: 145 receptions, 1,947 yards and 16 touchdowns.

Thursday night at the NFL Honors event, he was named Offensive Player of the Year.

He’s a little like Ali in his prime: The foe can barely lay a glove on him.

Well, there was that one time in Seattle. But, really, not even then.

In a 2018 game against the Seahawks his second season, he tore the ACL in his left knee. But there was no Seahawks villain. He just twisted it; a non-contact injury. That was year the Rams went to the Super Bowl, where they lost 13-3 to New England.

“Missing that Super Bowl, that’s one of the hardest things I’ve been through,” Kupp told reporters this week in Los Angeles. “The conflict it creates in you when you are both cheering and pulling for your guys. You equally want them to succeed and do it, but also wanting to be there and knowing that you can’t be a part of it, like you want to, at least. That’s a very difficult thing to go through.”

Had Kupp been available, there’s a good chance a bit of Super Bowl history would have been re-written.

Four years earlier, he barely missed a chance to re-write some University of Washington football history.

In the highly anticipated first home game for new Huskies coach Chris Petersen, Kupp and his Eastern Washington University teammates nearly did to Petersen’s career what another Big Sky Conference school, Montana, did in 2021 to Jimmy Lake’s career — help sink it before it really started.

After a 3-1 debut in a 2020 season truncated by COVID-19, Lake’s team was ranked 20th in the AP poll, yet fell in the opener to Montana 13-7. It was the Grizzlies’ first win over Washington in 101 years. Lake didn’t finish the season in the job.

On Sept. 6, 2014, Lake was defensive backs coach when the Eagles swooped all over some frightened Dawgs.

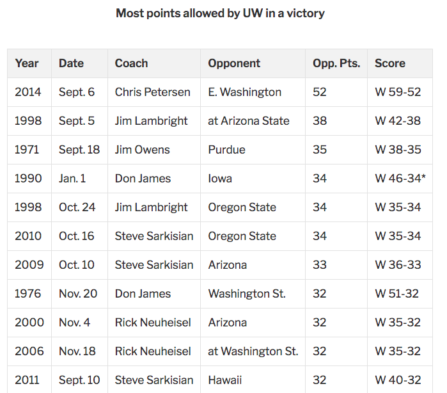

The Huskies barely survived, 59-52, likely only because they recovered an onside kick late in the fourth quarter. The outcome made a little UW history: It was the most points ever surrendered by Washington in a win.

QB Vernon Adams passed for 475 yards and seven touchdowns, two more than the previous opponent record. Kupp caught eight passes for 145 yards and three TDs.

On defense that game, the Huskies had Shaq Thompson, Danny Shelton, Budda Baker, Kevin King, Sidney Jones, Marcus Peters and Cory Littleton — all eventual NFL players.

“We barely escaped and got a win. I remember that,” Lake said later. “That was a talented team that came in here and they made a bunch of plays on us. Thankfully our offense made one more play than they did.

“I try to block that game out of my head as much as I can. That was a tough one, obviously, on defense.”

How Kupp escaped the recruiting attention of the four Northwest Pac-12 Conference schools is a mystery. But he made them pay.

Eastern played all of them during Kupp’s four years, which included a win over Washington State in 2016 when he went 12-206-3. Kupp’s totals vs. the Pac-12: 40 catches, 716 yards, 11 TDs.

Nevertheless, he was overlooked in the 2017 draft by the Seahawks too — and everyone else, lasting until the 69th pick of the third round, when the Rams pounced. But at least the Seahawks took Malik McDowell, all-terrain-vehicle poster child.

Although injuries limited his rookie season to eight games, he used rehab time to refine his route-running techniques that appear to distinguish him from the rest of the NFL’s receivers.

“I could teach myself to run the way that I wanted to run,” he said this week. “I could run routes the way I wanted to run routes; I could cut the way that I wanted to cut, eliminate any bad habits and be able to move into a place where all that stuff is as efficiently and dialed in as I could possibly make it.”

His football genes and instincts go back at least two generations. His grandfather, Jake Kupp, went from Sunnyside High, near Yakima, to UW, where he was an offensive guard for four years in the early 1960s under coach Jim Owens. In 1965, he was drafted in the ninth round by the Dallas Cowboys and played 13 seasons for four teams, making 131 starts in 154 games. Part of his last nine seasons were spent in New Orleans blocking for Archie Manning.

Jake’s son and Cooper’s father, Craig, was a Division III All-America quarterback at Pacific Lutheran, where he met and married Karin Gilmer, a soccer All-America selection. Both are in PLU’s sports hall of fame. Craig was drafted in the fifth round in 1990 by the Giants, and had bench time with the Cowboys and Cardinals.

That makes three NFL generations. Not sure if another family in the state can make such a claim.

A lot of football people in this state wish they had made a claim on Cooper Kupp.

Rams 27, Bengals 19