Boxing locally and nationally is rarely on the mainstream radar anymore. But in Seattle’s less dilettante days, thanks to colorful — and creative — boxing promoters such as Nate Druxman, Jack Hurley and George Chemeres, there were a good number of nationally-ranked pugilists, including Olympic champs, who brought excitement and big names to town.

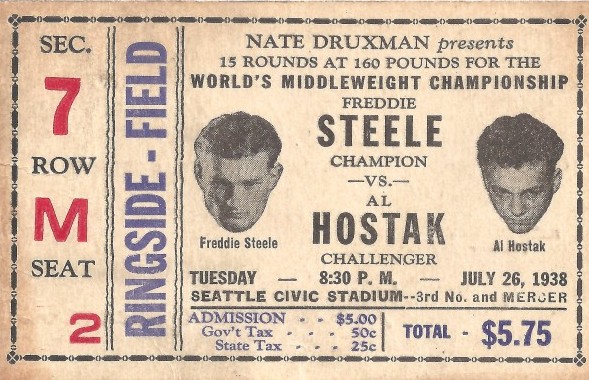

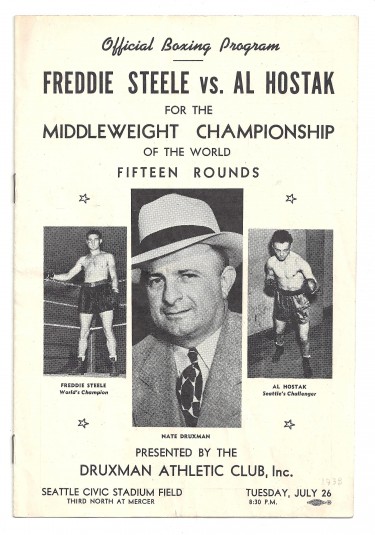

Of the many championship fights held in Seattle, including the Aug. 12, 1957, world heavyweight title extravaganza between Pete Rademacher and Floyd Patterson at Sicks’ Stadium, none captivated the fancy of local pugilism enthusiasts more than the National Boxing Association world middleweight title bout July 26, 1938 at Civic Stadium (located at 3rd and Mercer) between a pair of locals, Seattle’s Al Hostak, the “Savage Slav”, and Freddie Steele, the “Tacoma Assassin”.

Boxing fans snarfed up more than 30,000 tickets to the fight in a matter of hours. A Seattle “betting commissioner” told The Seattle Times in its July 26, 1938 edition that at least $25,000 had been wagered in downtown cardrooms — and probably a lot more than that, an incredible sum back in the day. The raging interest over the Steele-Hostak matchup meant that Steele, as defending champion, would receive a guaranteed $30,000, while Hostak, as challenger, would collect $8,462.64, or 12 1/2 percent of the purse.

Born in Seattle (1912) but reared in Tacoma (attended Bellarmine High), the 5-foot-10, 159-pound Steele had played baseball, basketball, soccer and table tennis as a youth. Steele won his first amateur bout in 1926 and did not lose until his 47th fight, to Tony Portillo Dec. 30, 1930. He made his professional boxing debut July 7, 1932, won the Pacific Northwest welterweight title in 1933, and became NBA world middleweight champion Feb. 19, 1937, by scoring a unanimous, 15-round decision over Babe Risko at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

Born in Minneapolis to Czech immigrants, the 6-foot, 156-pound Hostak, a Minneapolis native, grew up a tough kid in Seattle’s Georgetown neighborhood and became attracted to boxing when he was forced to defend himself against schoolmates who made fun of his stuttering.

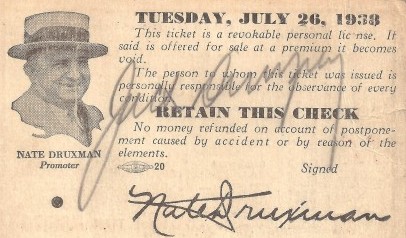

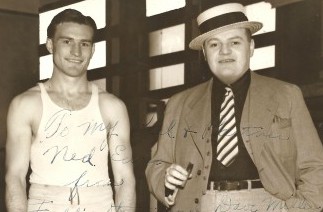

Nate Druxman, once an amateur baseball player, a not-so-successful boxer, and a man who sold cigars, jewelry, real estate and toiled in Seattle shipyards, had started promoting local boxing shows at the Seattle Elks Club at Fourth Avenue and Spring Street in August, 1914. A man of considerable ego, Druxman talked former heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey in August of 1931 into boxing three exhibition bouts with Denny Lenhart, a Portland pug, that filled Civic Arena. Two years later, on July 11, 1933, Druxman put together the first officially sanctioned world title fight in Seattle, a pairing of Freddie Miller and Abie Israel for the NBA featherweight title. Five years after that, Druxman brought Steele and Hostak together for a Civic Stadium showdown that has since gone down as one of the major spectacles in Seattle sports history.

Steele entered the ring with more than 120 official victories and only four losses in his portfolio, and installed as a slight favorite. He also entered as a fighter compromised by the lingering effects of a broken breastbone he had suffered in a loss to Freddie Apostoli seven months earlier (Jan. 7, 1938, at Madison Square Garden), and injuries he had received in a serious traffic accident (crashed into a stalled vehicle on the Seattle-Tacoma highway near the Fife junction).

Most experts figured that the fight would go the 15-round distance, and they figured wrong. The ballyhoo ended in a blink.

Wrote The Seattle Times in its July 27, 1938 edition that included a dozen photos of the event: “Steele made two bad mistakes, one for lack of a smart battle campaign and the other because he was too groggy to know better. His first mistake was when he came out swinging to meet the Savage Slav. There’s no middleweight in the business qualified to slug it out with Hostak. He hits too hard and too fast.”

Hostak landed the first punch and then floored Steele three more times before delivering the winning blow, a short, perfectly timed left hook to the button that sent Steele toppling pie-eyed to the canvas. Referee Jack Dempsey counted the decisive 10 at 1:43 of the first round.

Steele’s crushing loss, coupled with his previous injuries, essentially ended his boxing career. He did not fight again for three years, losing by TKO to Jimmy Casino at Legion Stadium in Hollywood, CA., May 23, 1941. That turned out to be Steele’s last fight, and he concluded his career with 125 wins (60 knockouts), five losses and 11 draws.

Hostak fought for 11 more years, finishing with 63 wins (42 by knockout), nine losses and 12 draws. He lost the world middleweight title he took from Steele, by majority decision, to Solly Krieger Nov. 1, 1938, at Seattle’s Civic Auditorium, after breaking both of his hands early in the fight and suffering the first knockdown of his career in the 14th round (Steele was among the first in the ring to console Hostak after his loss).

Hostak snatched back his title from Krieger in a rematch June 27, 1939, with a fourth-round TKO at Civic Stadium in front of 23,000 fans. It marked the first time a fighter had recaptured the world middleweight title since Stanley Ketchel did it against Billy Papke in 1908.

Hostak successfully defended his title Dec. 12, 1939, against Erich Seelig with a first-round KO at the Cleveland, OH., Arena. Then things dove south.

Hostak lost by unanimous decision to Tony Zale in a non-title bout in Chicago Jan. 29, 1940, in which Hostak broke his hands. Hostak broke his hands again July 19, 1940, when he officially lost his middleweight crown to Zale at Civic Stadium. When Hostak and Zale met for a third time, May 28, 1941, Hostak knocked Zale down in the first round, but lost the fight in the second after Zale knocked him down eight times.

Hostak’s last fight came eight years later, Jan. 7, 1949, when he scored a ninth-round knockout of Jack Snapp at Civic Auditorium.

Hostak entered the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1997. In 2003, Ring Magazine named him to its list of “The 100 Greatest Punchers of All Time.” “One of the greatest punchers I’ve ever seen,” said Dempsey, after the Steele-Hostak fight.

Steele, who entered the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1999, moved to the San Fernando Valley after his boxing days and had a career in the film industry from 1941-48. He served as a double for Errol Flynn in Gentleman Jim and had more significant roles in The Story of G.I. Joe (1944, with Burgess Meredith and Robert Mitchum), Black Angel (1946, with Dan Duryea and Peter Lorre) and Race Street (1948, with George Raft and William Bendix). After a decade in California, Steele returned to Washington state and, with wife Helen, operated “Freddie Steele’s Restaurant” in Westport, WA. They ran the establishment for two decades before illness forced his retirement. Steele died Aug. 24, 1984, in an Aberdeen nursing home from complications from a stroke. He is buried at Aberdeen’s Fern Hill Cemetery.

Hostak did a little bit of everything following his boxing career. He held jobs as a tavern owner, bartender, King County jail guard and security guard at Longacres Race Track. A White Center resident for many years, Hostak spent much of his leisure time haunting local flea markets, collecting musical tapes. He died Aug. 13, 2006, at Evergreen Hospice in Kirkland, WA., from complications of a stroke that he suffered on Aug. 2, 2006.

Druxman, whose promotional efforts on behalf of Steele vs. Hostak resulted in a paid attendance of 30,201 and gate receipts of $85,031 (State Athletic Commission figures), wound up flaking 11 world title fights in Seattle, his last July 19, 1940, when Zale TKO’d Hostak in the 13th round at Civic Stadium. Druxman, who sold millions of dollars worth of war bonds during World II, died in 1969. The 11 world title fights he promoted in Seattle:

- July 11, 1933: Freddie Miller def. Abie Israel, KO 4 (NBA featherweight title, Civic Ice Arena).

- April 9, 1935: Barney Ross def. Henry Wood, UD 12 (world light welterweight title, Civic Auditorium).

- Feb. 18, 1936: Freddie Miller def. Johnny Pena, UD 10 (NBA featherweight title, Crystal Pool).

- July 11, 1936: Freddie Steele def. Eddie (Babe) Risko, UD 15 (NBA and NYSAC middleweight title, Civic Stadium).

- May 11, 1937: Freddie Steele def. Frank Battaglia, KO 3 (NBA and NYSAC middleweight title, Civic Auditorium).

- Sept.11, 1937: Freddie Steele def. Ken Overlin, KO 4 (NBA and NYSAC middleweight title, Civic Auditorium).

- July 26, 1938: Al Hostak def. Freddie Steele, KO 1 (NBA middleweight title, Civic Stadium).

- Nov. 1, 1938: Solly Kreiger def. Al Hostak, MD 15 (NBA middleweight title, Civic Auditorium).

- June 27, 1939: Al Hostak def. Solly Kreiger, TKO 4 (NBA middleweight title, Civic Stadium).

- Oct. 20, 1939: Henry Armstrong def. Ritchie Fontaine, TKO 3 (world welterweight title, Civic Auditorium).

- July 19, 1940: Tony Zale def. Al Hostak. TKO 13 (NBA middleweight title, Civic Stadium).

————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi, who writes The Wayback Machine every Tuesday. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at the following e-mail address: seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

6 Comments

I visited with Al in his White Center home when he was 72 and he recalled his first pro fight, when he floored his opponent four times in the first round. His purse was a buck and a half. And he had to give his manager a dollar, for gym dues. That left him 50 cents which he spent on a greeting card to his closest fan. On the back he scrawled, “May 20, 1932. First fight won. To Mom.”

John Owen was one of the greatest sports writers in Seattle history. He also knows how to cook like nobody’s business.

Great story

Barry Druxman

Great story

Barry Druxman

Ezkenazi, I am so grateful that you built such a wonderful collection and share it with the rest of us that recall fondly an era of not so long ago and those that starred in it. Hostak was a lifelong buddy of my grandfathers, John Nenezich. I met Al at my grandfathers funeral (Pallbearer) and I will never forget him. As soon as I stepped out of the car at the service Al had me laughing and also had no problem breaking my balls even my grandfather’s funeral. Here’s to Al Hostak!

Ezkenazi, I am so grateful that you built such a wonderful collection and share it with the rest of us that recall fondly an era of not so long ago and those that starred in it. Hostak was a lifelong buddy of my grandfathers, John Nenezich. I met Al at my grandfathers funeral (Pallbearer) and I will never forget him. As soon as I stepped out of the car at the service Al had me laughing and also had no problem breaking my balls even my grandfather’s funeral. Here’s to Al Hostak!