By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

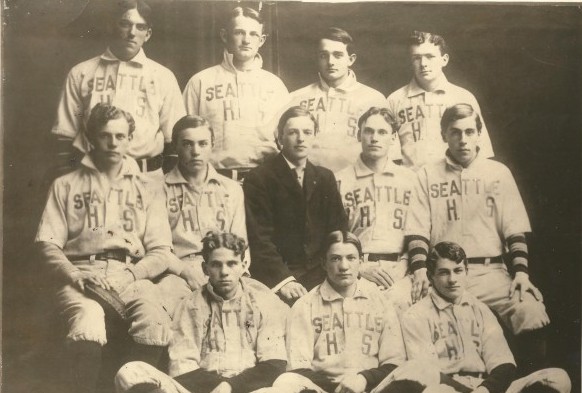

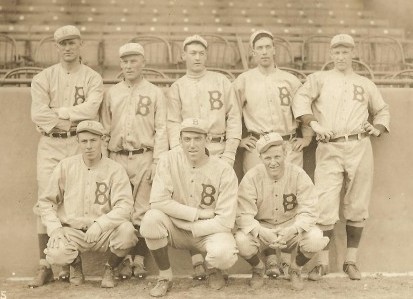

On June 14, 1907, the Seattle High School baseball team (later Broadway High School) departed town on the Northern Pacific Railroad, bound for an unprecedented tour of the East, Midwest and Southwest to help promote the upcoming (1909) Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exhibition, a worlds fair of sorts conceived to tout the economic opportunities in the Pacific Northwest and advertise Seattle as the gateway to the wealth and luck of Alaska.

By the time the boys, as local newspapers frequently called them, arrived at King Street Station two months later (Aug. 13), having more than exhausted the $3,600 that local businesses had anted up to fund their journey, they traveled 8,600 miles and played 31 games in 10 states and the District of Columbia against an assortment of high school and town teams, business college nines, and even professional clubs.

No other high school in America nor college, for that matter had ever undertaken such an ambitious junket, and the success that Seattle High had on the trip made them local celebrities. As soon as the players decamped the train, to the cheers of more than 1,000 friends and supporters, Seattle city officials piled them into a tally-ho and threw them a parade replete with a brass band and a predictable phalanx of preening politicians.

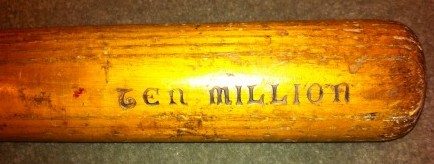

According to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, proud well wishers stood on crates where they craned and gawked to get better views of whiz spitballer Charlie Otto Schmutz; the intriguingly named left fielder Ten Million; speedy center fielder Wee Coyle, who had picked up his less-than-flattering moniker from a large First Hill bully named Maureen; and Charlie Mullen, a first baseman of such exceptional talent that many believed he was already ready to play professionally.

The boys made a splendid showing, The Seattle Times wrote, winning the majority of the games they played, and the reception given them at the train station was a fitting climax to one of the most remarkable trips ever undertaken by a club of young athletes.

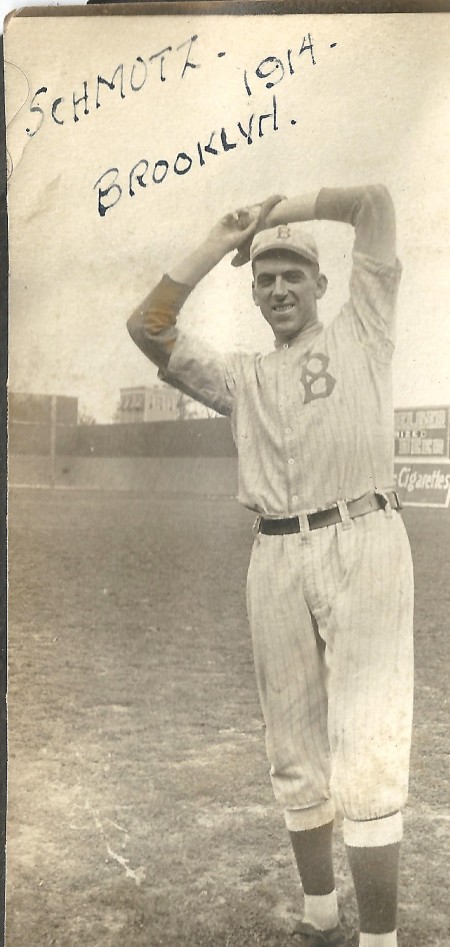

Remarkable, if not astonishing, about the 1907 Seattle High team is the number of them who went on to play professionally. Two months before (April 17) Seattle High embarked on the trip, 16-year-old Schmutz provided a preview of both the tour and his own career when, in a performance that shocked Seattles sporting citizenry, he tossed a two-hit, 2-1 victory over Dan Dugdales Northwestern League professional team in an exhibition game at Yesler Way Park.

Schmutz would reach the major leagues with the Brooklyn Robins (Dodgers) within seven years. Mullen, the 5-10, 155-pound first baseman, would get to the majors, with the Chicago White Sox, even faster in just three years.

Two other Seattle High players left fielder Million and pitcher Jimmy “Toots” Agnew would both spend time in the mid-to-high minor leagues, and Million probably would have reached the majors if he hadnt suffered a knee injury.

Third baseman Harry Mitt Martin had enough ability to play in the low minors, for Chehalis of the Washington State League. Three others catcher and captain Mert Hemenway, outfielder Fred Hickenbottom and shortstop Ernie Maguire became University of Washington letter winners.

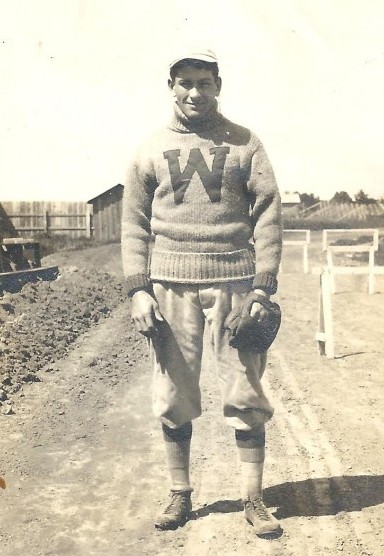

Centerfielder Coyle, coveted by both the University of Washington and the University of Oregon for his baseball and track (hurdles) skills, would become famous for leading the Washington football team to a 26-0-1 record during his four varsity seasons (1908-11) as Gil Dobies starting quarterback.

Only second baseman Roe Hilton and right fielder Jay Smith failed to have an athletic career extend much beyond their days at Seattle High.

Schmutz and Agnew mainly handled the pitching chores during the tour, which began on June 18 in St. Paul, MN., against the St. Paul Athletic Club, whose roster included a number of college-age players. Schmutz tossed a one-hitter and fanned 13, while Million, Mullen, Coyle and Hemenway each produced two hits. Already nicknamed The Tourists by newspapers, Seattle High prevailed 2-1.

Schmutz pitched great ball and allowed but one hit, a Minneapolis newspaper recounted. Thirteen Athletics fanned the ozone before his puzzling delivery (during the tour, six different newspapers described Schmutzs delivery as puzzling).

The Tourists moved to Chicago for five games, including a pair against North Division High School in what amounted to something of a rematch.

The previous January (Jan. 1), North Division, for a $2,500 travel fee, arrived in Seattle to play Seattle High for the High School National Football Championship. The game, which attracted 8,000 to a muddy Madison Park, featured a ticket price of $1 and, intriguingly, an umpire by the name of Hiram Conibear, who then worked as the athletic trainer for the Chicago White Sox and University of Chicago.

Conibear came west with North Division and was sought out to umpire on the day of the game. Three years later, Conibear would return to Seattle as the UWs new rowing coach.

The game came down to the final 48 seconds with North Division holding a 6-5 lead. Wrote The Times:

There was more betting on this game than any ever played in Seattle. And the best football game ever played in Seattle was pulled off under conditions most distressing. Madison Park was packed to the bulging point and half the crowd stood in black ooze ankle deep. The sidelines were obliterated in the mud and big fat policemen jammed their sticks into the ribs of Seattles chivalry, trying to clear the field enough for the boys to play.

Coyle directed what turned out to be the winning drive because he successfully executed one of the riskiest plays in the game a forward pass. Under rules of the day, an incomplete pass resulted in a 15-yard penalty. At the same time, a pass completion of more than 20 yards also resulted in a 15-yard penalty. Correctly gauging the distance he needed, Coyle completed a pass estimated at 18 yards to Penny Westover, setting up Westovers game-winning touchdown run.

Six months later, Coyle occupied center field for the Seattle High baseball team when its tour reached the Windy City for the two games against North Division — Chicago newspapers made much of the “rematch” — and two others against Wendell Phillips Academy, the interscholastic champions of the Midwest.

After Seattle Highs first contest, a 3-0 win over North Division on June 19, a Post-Intelligencer correspondent said, In a game as fast and interesting as any major league contest, a large crowd at Ganther Park watched Seattle win through the magnificent pitching of (Jimmy) Agnew, who had the local sluggers guessing and completely at his mercy.

“He made 15 of them go back to the bench after fanning. Only three hits were made off him . . . The presence of the Seattle team in the city and the purpose of its coming has aroused widespread interest and comment.

A day later, Seattle defeated Wendell Phillips 14-6 as Hemenway, the regular catcher, ascended the mound and delivered a four hitter while Smith produced a double, three singles and a sacrifice fly.

The victories by Seattle High over Chicagos best prompted a Chicago newspaper to question whether Seattle employed ringers and professional players. Seattle High manager Harold Stewart finally had to produce birth certificates to prove that none of his players exceeded 18 years of age.

After Seattle finished the Chicago leg of its journey by winning three of the five games, the Chicago Tribune wrote, The Seattle players were shown considerable attention by Coach (Amos Alonzo) Stagg of the University of Chicago (an innovator responsible for the center snap and onside kick, among others). He is said to be particularly interested in Coyle as a football player.

Charlie Mullen is good enough to play professional baseball right now. Schmutz and Jimmy Agnew are first-class young pitchers, and when they get a little more experience they will be able to hold their own in almost any company.

Schmutzs next victory came June 26 in Scranton, PA, where he whitewashed Lackawanna Business College 2-0.

Schmutz had the locals faded at all times, a Seattle Times report stated. This elongated youngster with his puzzling delivery allowed but two hits. He struck out a batter each inning.

For Seattle High, the least-successful part of its trip occurred between June 28 and July 15, when the team whisked through Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Hagerstown, MD, and Martinsburg, W.VA, and lost seven times.

But four of the defeats were administered by professional clubs, one by an athletic club and one by a college team.

In some places, the high schools pleaded vacation time and could not get their teams together, so the boys were forced to play professional teams, manager Stewart told the Post-Intelligencer. In Philadelphia, they (Seattle High) played the professional Philadelphia Giants and were only beaten by one run.

Seattle High managed two wins in four games during its stopover in the nations capital, including a 10-1 triumph July 6 over Western High School, champions of the East, which featured a no-hitter by Schmutz.

Schmutz really caused the local lads downfall, wrote the Washington Times. Schmutz, who used the spitball, did not allow a hit. His work of retiring the side on strikes, or when a man was on base, was well appreciated by the large crowd and he was given an ovation.

“A glance at the box score will show what fine work the visiting pitcher did. He fanned 13 batters, did not allow a hit, and not one of his outfielders had a putout.

Following Schmutzs 4-3 July 10 victory over Postoffice, a semi-pro club comprised of federal government workers, the Washington Post opined: Schmutz again proved somewhat of a wonder as an amateur pitcher. And in Mullen, the visitors presented one of the best amateur first sackers that has been seen in these parts for some time.

When Seattle High concluded its visit to Washington, D.C., the Washington Times said, Seattle is easily the strongest high school team ever seen in these parts.

“These players are as good as professionals. The Washington Star echoed that sentiment: The Seattle team is better than the college teams that have visited the city.

Schmutz collected another shutout on July 17, defeating Charlottesville (VA.) High 3-0. Then, over the next 13 days, Schmutz pitched four games, winning against high school teams in Lewisburg, W. VA and Dwight, IL., and a professional team in Abilene, TX. He also held Central High in St. Louis to two hits, but lost 1-0.

While in Texas, Seattle High made a name for itself by beating the Abilene professional team three out of four games, reported manager Stewart.

This is the first time that Abilene has been beaten in a series in seven years.

Upon the teams return to Seattle, the Times advised, When the team first left Seattle many thought it was grave mistake to send a high school team all over the country. But the boys entertained many, and as a result, Seattle and the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exhibition have been advertised.

We were up against all kinds of teams and some of them were being paid big money to play the game, Stewart told the Post-Intelligencer. At Pontiac (IL.), they hired especially to meet us a catcher and a pitcher that cost them $100 for the afternoon.

We played at Dwight (IL.), which is the headquarters for the Keeley cure for drunkenness (officially The American Association for the Study and Cure of Inebriety), and all the jags turned out to see us play and cheer for us. And at Abilene (TX.), we went up against the best nine in that state and won three out of four games.

Although we lost our scorebooks somewhere, (Jay) Smith and (Charlie) Mullen both had batting averages of .300.”

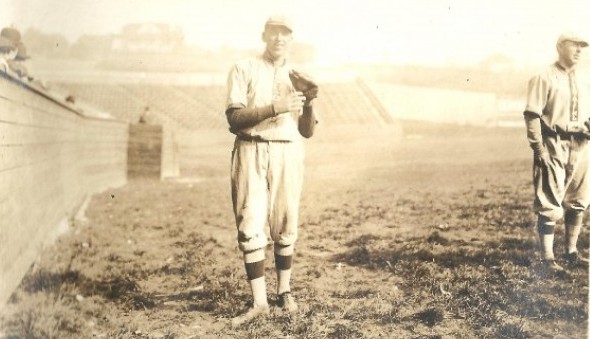

But Schmutz was the principal reason why Seattle High finished the trip with a winning 16-15 record, and his career was just taking off.

Born Jan. 1, 1891 in San Diego, Schmutz had already introduced himself to the Seattle populace on April 17, 1907, when, utilizing a nasty spitball, he flummoxed Dugdales Siwashes 2-1. Aided by Coyles two doubles, while overcoming Coyles three errors in center, Schmutz allowed just two hits and fanned eight.

A headline the next day blared: High School Beats Seattle. Schmutz Is Wizard.

A long-legged lad named Schmutz, who has not before been considered good enough for his high school team, pitched a great game and had Dugs hired men buffaloed, declared the Post-Intelligencer, which paid no attention to any of Dugdales operatives and instead focused most of its coverage on Schmutz.

Mr. Schmutz, a pitcher of the bean-pole variety, had been nourished carefully by the high school as a dark horse, but was the stumbling block that Dugdales men could not overcome, the Post-Intelligencer continued.

From dizzying heights (Schmutz stood 6-foot-1), he handed them (his pitches) down so that only two hits were chalked against him. Strictly speaking, Dugs hired men had only one hit off Schmutzs delivery, by St. John in the fourth inning after two were out. The safety given Hickey was nothing more than error of judgment in (Schmutz) delaying a throw to first after his grounder had been fielded.

Schmutz launched his professional career in 1910 with a Tacoma (Northwestern League) team managed by the legendary Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity (newspapers of the era often used I.M. McGinnity in headlines). Schmutz had subsequent minor league stops in Vancouver (1912-13), Salt Lake City (AA, 1915), Newark/Harrisburg (AA, 1915) and Seattle (Northwestern, 1916).

In 1912, Tacoma traded Schmutz, now nicknamed King, to Vancouver for five players, including former Seattle High teammate Jimmy Agnew. Then, in 1913, Vancouver sold Schmutz to the Ebbets Field-based Brooklyn Robins, the National League club managed by Wilbert Robinson.

Schmutz pitched in 19 games for Brooklyn in 1914-15, compiling a 1-3 record. While in Brooklyn, he played with the likes of Nap Rucker and future Hall of Famer Zach Wheat, and roomed with Casey Stengel, the Robins regular right fielder and later a Hall of Fame manager.

Following the 1915 season, Schmutz came down with malaria and was farmed out to Seattle for the 1916 season. He won 19 games for a Giants team that finished in fifth place with a record of 60-72.

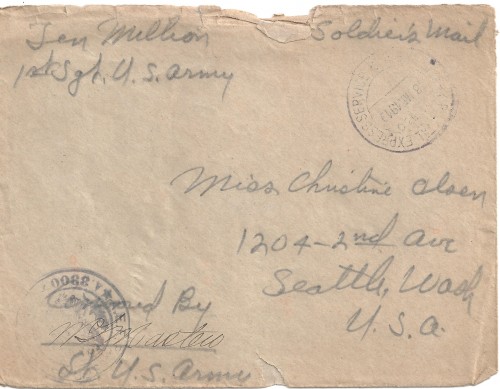

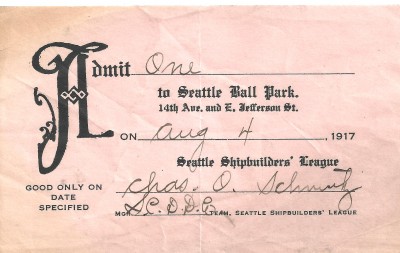

Schmutz might have returned to the major leagues, but World War I took him out of baseball for good in 1917. Schmutz went overseas with the famous 91st Wild West division from Camp Lewis, a doughboy in the 362nd infantry. He served, mostly in France, until June of 1919, attaining the rank of sergeant.

After returning to Seattle, the 28-year-old Schmutz went to work for the Graybar Electric Company, spending 25 years in its employ, retiring in 1957. A member of the Washington Athletic Club and American Legion Post 1, he actively involved himself in Legion ball for many years, and also served a stint on the board of directors of the Seattle Rainiers.

Charlie Otto Schmutz died on June 27, 1962, in Seattle, at the age of 71.

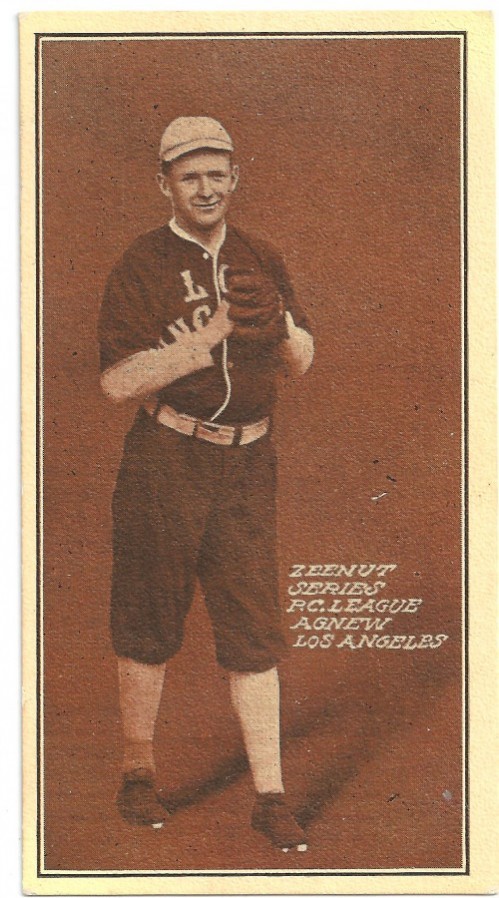

Schmutzs pitching partner on the 1907 Seattle High team, Jimmy Toots Agnew, was born in Portland and moved to Seattle when he was a year old. The son of P.J. Agnew, an early-day King County auditor, “Toots” launched his pro career in 1911 when he joined Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League.

He had such a poor debut season, going 5-20, that Los Angeles sold him in 1912 to Vancouver of the Northwestern League. A year later, Vancouver traded him to Portland, where he injured his arm and never pitched again.

Agnew finished his pro career with a 19-34 record and served as a lieutenant with the 20th Engineers Regiment in France during World War I (where he met his wife, Jano). He spent the 30 years following World War I as a pharmaceutical sales representative, and then went to work for the King County engineer’s office. Jimmy Agnew died on Feb. 26, 1953, in Seattle at the age of 63 following a short illness.

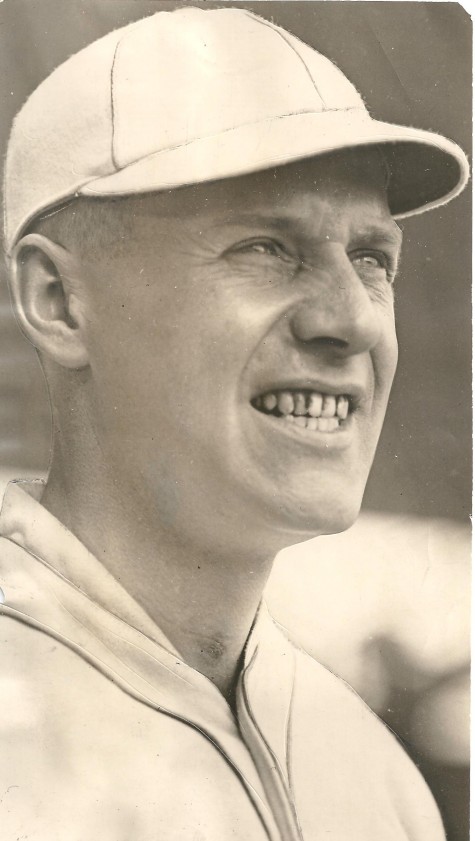

Born March 15, 1889, Charlie Mullen joined the New York Yankees the same year (1914) that Schmutz arrived in Brooklyn. At Seattle High School, Mullen captained the baseball, basketball and track teams and earned one letter in football.

Mullen had launched his pro career with Portland of the Northwestern League in 1909, just two years out of Seattle High School.

By 1910, after short stays with the Winchester Hustlers of the Blue Grass League and the Lincoln Railsplitters of the Western League, Mullen found himself in the major leagues for the first time, signed by Charles Comiskey, with the Chicago White Sox.

Mullen played in 61 games for the White Sox in 1910-11, but couldnt hit well enough (.200) to stick. After he spent two more seasons in the minors (he became a player-manager with Lincoln of the Western League), the White Sox sold Mullen to the Yankees, where he replaced Hal Chase, who had gone to the White Sox (SABR calls Chase “the most notoriously corrupt player ever and the greatest defensive first basemen ever”) .

In 1925, Lou Gehrig launched his famous 2,130-game playing streak after replacing Wally Pipp as New Yorks first basemen.

A decade earlier, in 1915, Pipp became the Yankees first baseman when he replaced Charlie Mullen. Pipps conscription of the job effectively ended Mullens time in the majors.

During World War I, Mullen served as an infantry lieutenant and Army baseball coach. Among his ballplayers during the war: Ten Million.

Mullen finished out his baseball career with AA Toledo (1917) and the 1919 Seattle Rainiers. After appearing in 39 games (hit .272), Mullen took over as club manager from Bill Clymer midway through the season (in 1920, Mullen became manager of the Tacoma Tigers).

(Seattle had been a charter franchise in the Pacific Coast League in 1903, and dropped out of the PCL after the 1906 season. Seattle became a member of the Northwestern League, and its other incarnations, from 1907-18, then re-joined the PCL in 1919.)

Mullen joined H.M. Herrin & Co., a securities firm, after leaving baseball, and later became president of the Seattle Stock Exchange. He died on June 6, 1963, at age 74, in Seattle, preceded in death by about one year his former teammate and protoge, Ten Million, who never played a day in the majors, but was good enough to star at the University of Washington and play several years in the minor leagues.

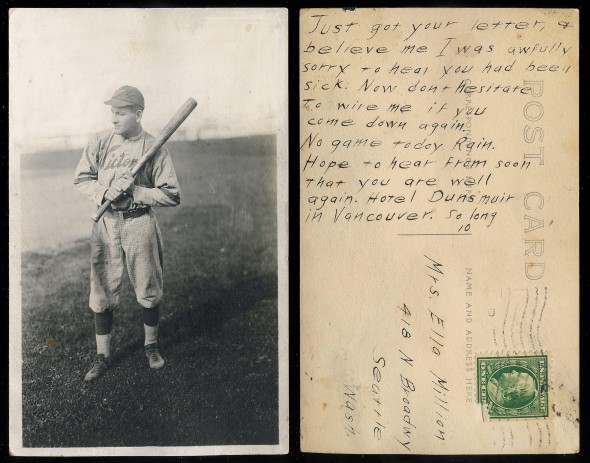

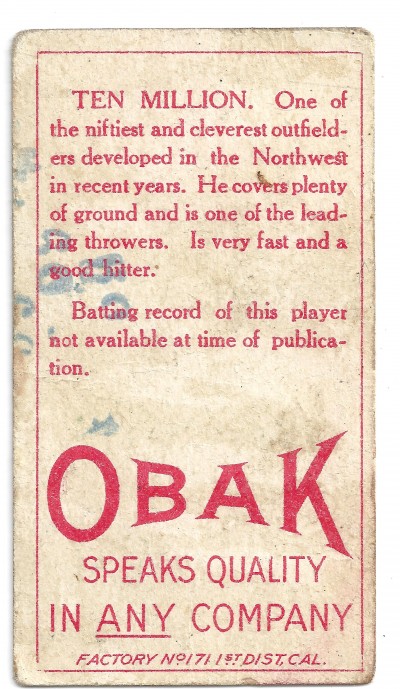

Born on Oct. 14, 1889, just a few months after the Great Seattle Fire, Ten Million graduated from Seattle High in 1908.

The son of a prominent judge, E.C. Elmer Million, Ten got his name because, with the last name of Million, his mother wanted her son to stand out. As the Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia explained it, Tens mother had a penchant for the unusual.

When, years later, Ten and his wife, Christine, had a daughter, Tens mother bribed them with $50 to name her Decillian Million, so that she would be known as Decillian Million, daughter of Ten Million. Decillian Million later used the nickname Dixie.

Ten Million earned one varsity letter at the University of Washington (1910) and began his professional career with the Victoria Bees of the Northwestern League (1911).

After he hit .276 in 160 games for the Bees that year, the Cleveland Naps purchased his contract. But Ten Million never played in the majors due to a knee injury. In fact, he never officially made the team.

So Ten Million returned to the west and embarked upon what became a 692-game minor league career with stops in Tacoma, Sioux City (Western League), Spokane (Northwestern League) and Moose Jaw (Western Canadian League). Ten Million ended his career with a third tour in Tacoma (1912-14), playing under Iron Man McGinnity.

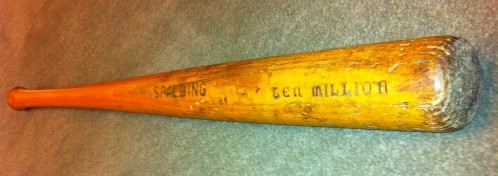

Done with baseball, Ten Million relocated to Seattle in 1915, served in the Army during World War I, and then returned to Seattle, where he worked as a claims adjuster, then for Spalding Sporting Goods, and kept active in sports by refereeing high school football, basketball and baseball games.

Ten Million also sold Ford automobiles. When Ford rolled its 10 millionth car off the assembly line, in the 1920s, the company shipped the vehicle to Seattle so that Ten Million could be the one to sell it, an event that rated a newspaper article and photograph.

When he finally retired, Ten Million purchased a house near Deception Pass. He died June 18, 1964, in an Anacortes hospital following a long illness. He was 74.

Born March 18, 1888, in Sutter Creek, CA., William Jennings Coyle grew up in a house on Broadway and Terrace on Seattles First Hill. Six weeks after Coyles father, William John Coyle, purchased the property, the Coyles had a ringside seat for the Great Seattle Fire that destroyed 30 blocks of downtown Seattle.

According to a fascinating memoir by Will Lomen, Wee Coyles grandson, his grandfather received his moniker while in grammar school (Charlie Mullen was a school mate) from a neighborhood bully, a girl named Maureen, who taunted Coyle relentlessly. Coyle eventually grew out of his weeness, topping out at 5-foot-10 and 150 pounds, but Maureens nickname dogged him the rest of his days.

Youre a little wee wee! Youre a little wee wee! I dont know whether my grandfather had a clever retort but the name stuck, and he carried the shortened version Wee, with pride, for the next eighty-plus years,” Lomen writes in his memoir. “As he grew in stature, he kept his speed and translated his elusiveness into skills that were ideal for a running quarterback, a ground-covering centerfielder, a swift track runner and a quick and crafty basketball guard.

Coyle could have pursued a professional baseball career, as Ten Million did.

Coyle earned two baseball letters at the Univeristy of Washington (1909-10), showing enough that the UW inducted him into its Hall of Fame as a baseball player.

Coyle also could have pursued a track career. Bill Hayward, the famous Oregon coach after whom the schools track facility (Hayward Field) is named, wanted Coyle as a hurdler.

Instead, Coyle enrolled at Washington where he earned eight letters in three sports, including four in football, three in baseball and one in track, and became known, primarily, as the only quarterback in school history to go undefeated (26-0-1) for his career.

Instead of pursuing a professional athletic career, Coyle became an attorney, and while practicing law in Eastern Washington in 1915 he coached the Gonzaga University football team, which lost to Dobie and Washington 21-7. Coyle thus became the first ex-UW player to coach against his alma mater.

Coyle wore a variety of hats after that. He became lieutenant governor from 1921-1925 (the Republican Party) and manged the Seattle Civic Auditorium from 1928-53. Coyle died on Oct. 1, 1977 in Seattle.

The Seattle High team that toured the country in 1907 held several periodic reunions, as almost all of the players spent their post-baseball careers in the Seattle area. Harold Stewart, who managed the team, had the best synopsis on the summer of 1907.

We traveled 8,600 miles and over every one of them we attempted to leave something behind that would make people think of Seattle,” he said.

Seattle High’s 1907 Tour

| Game | Date | Location | Result | Rec. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | June 18 | St. Paul, MN | Seattle 2, St. Paul Athletic Club 1 | 1-0 |

| 2 | June 19 | Chicago, IL | Seattle 3, North Division High 0 | 2-0 |

| 3 | June 20 | Chicago, IL | Seattle 14, Wendell Phillips High 6 | 3-0 |

| 4 | June 20 | Chicago, IL | Seattle 5, Frane & McKinley High 0 | 4-0 |

| 5 | June 21 | Chicago, IL | North Division High 4, Seattle 1 | 4-1 |

| 6 | June 22 | Chicago, IL | Wendell Phillips High 6, Seattle 4 | 4-2 |

| 7 | June 25 | Detroit, MI | All-Detroit High 3, Seattle 2 | 4-3 |

| 8 | June 26 | Scranton, PA | Seattle 2, Lackawanna Business 0 | 5-3 |

| 9 | June 28 | Brooklyn, NY | Richmond Hills High 6, Seattle 2 | 5-4 |

| 10 | July 2 | Philadelphia, PA | Frankford AC 5, Seattle 0 | 5-5 |

| 11 | July 3 | Philadelphia, PA | Phila. Giants (pro) 5, Seattle 4 | 5-6 |

| 12 | July 6 | Washington, D.C. | Seattle 10, Western High 1 | 6-6 |

| 13 | July 10 | Hagerstown, MD | Hagerstown (pro) 4, Seattle 3 | 6-7 |

| 14 | July 12 | Washington, D.C. | St. Stephen’s College 9, Seattle 3 | 6-8 |

| 15 | July 13 | Washington, D.C. | Seattle 4, Post Office 3 | 7-8 |

| 16 | July 14 | Martinsburg, WVA | Martinsburg (pro) 8, Seattle 4 | 7-9 |

| 17 | July 15 | Martinsburg, WVA | Martinsburg (pro) 4, Seattle 2 | 7-10 |

| 18 | July 16 | Charlottesville, VA | Seattle 5, Charlottesville High 1 | 8-10 |

| 19 | July 22 | Lewisburg, WVA | Seattle 3, Lewisburg High 0 | 9-10 |

| 20 | July 23 | Lewisburg, WVA | Seattle 2, Lewisburg High 2-0 | 10-10 |

| 21 | July 23 | Lewisburg, WVA | Seattle 6, Lewisburg High 4 | 11-10 |

| 22 | July 24 | Dwight, IL | Seattle 6, Dwight High 5 | 12-10 |

| 23 | July 25 | Pontiac, IL | Pontiac High 3, Seattle 0 | 12-11 |

| 24 | July 27 | St. Louis, MO | St.Louis High 3, Seattle 0 | 12-12 |

| 25 | July 31 | Abilene, TX | Seattle 3, Abilene (pro) 1 | 13-12 |

| 26 | July 31 | Abilene, TX | Seattle 4, Abilene (pro) 3 | 14-12 |

| 27 | Aug. 1 | Abilene, TX | Seattle 5, Abilene (pro) 2 | 15-12 |

| 28 | Aug.1 | Abilene, TX | Abilene (pro) 12, Seattle 3 | 15-13 |

| 29 | Aug. 3 | Merkel, TX | Seattle 7, Merkel (pro) 3 | 16-13 |

| 30 | Aug. 5 | Merkel, TX | Merkel (pro) 9, Seattle 3 | 16-14 |

| 31 | Aug. 7 | Merkel, TX | Merkel (pro) 2, Seattle 1 | 16-15 |

———————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

3 Comments

Enjoyed the article. Always a pleasure to visit the Wayback Machine. – NC Murray

Enjoyed the article. Always a pleasure to visit the Wayback Machine. – NC Murray

Corrected, thank you.