By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

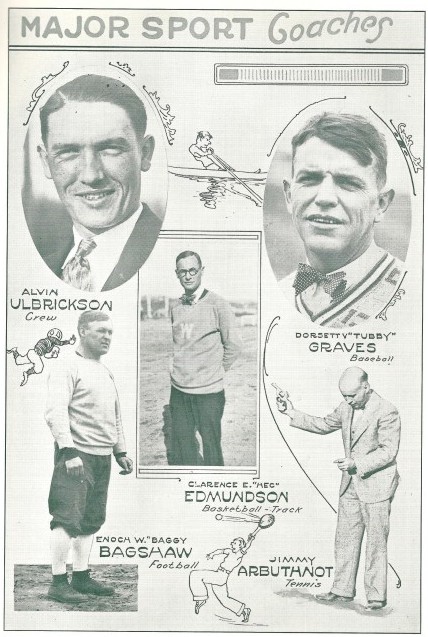

Few coaches in Washington state history influenced as many athletic lives as Clarence Sinclair Edmundson, who supervised the University of Washington track program for 36 years, the schools basketball team for 27, and co-invented (with Tubby Graves) the state high school basketball tournament in 1923.

So significant was Edmundsons impact that when his former athletes threw him a retirement dinner on May 28, 1954, at the Olympic Hotel, nearly 400 came from all over the world to attend.

Today, Edmundsons name is associated primarily with the universitys athletic pavilion, named in his honor at the time of his retirement. But back in his day, Edmundson was regarded by many as the greatest coach in the school’s history, and considered a resident genius, responsible for introducing up-tempo, fast-break basketball to the West Coast, coaching a string of All-Americans in that sport, and producing the first athletes from Washington to represent the school in the Summer Olympic Games.

Edmundson coached the UW basketball team (1921-47) nearly twice as the next-longest tenured UW coach, Marv Harshman (1972-85). He directed the schools track program (1919-54) a half a decade longer than the next-longest tenured coach, Ken Shannon (1968-97).

Edmundson might have coached even longer if a meddlesome athletic director named Harvey Cassill hadn’t poked his nose where even he came to admit it didnt belong, and if Edmundson hadnt been felled by a minor stroke.

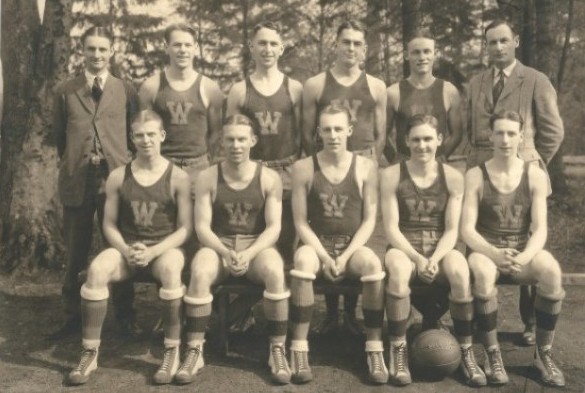

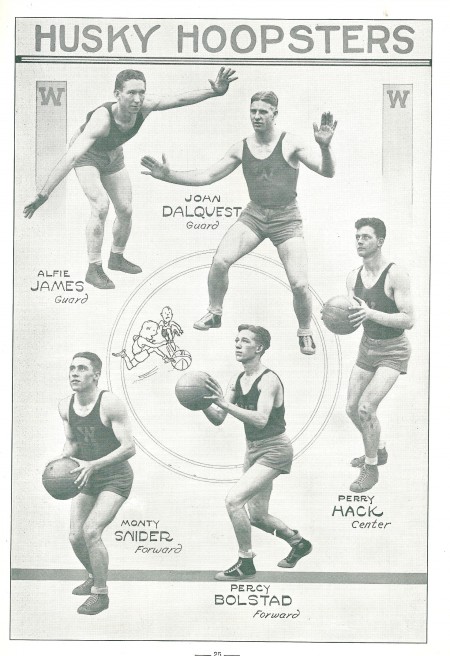

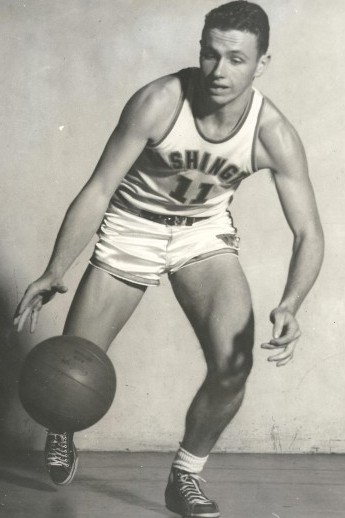

Of the 18 All-America basketball players in UW history, Edmundson coached seven, starting with guard Alfie James in 1928 and ending with another guard, “Battleship” Bill Morris, in 1943. Of the 21 basketball players enshrined in the Husky Hall of Fame, Edmundson tutored 11.

Of the 13 track athletes in the Husky Hall of Fame, Edmundson worked with eight, including the schools first three Summer Olympic medalists, discus thrower Gus Pope (1920, bronze), hurdler Steve Anderson (1928 silver) and shot putter Herman Brix (1928, silver).

Edmundson had been an Olympian himself (first Idahoan to take part in the Games), a middle-distance runner at the 1908 (London) and 1912 (Stockholm) Games, the latter starring athletic icon Jim Thorpe, winner of the decathlon and pentathlon. A sixth-place finisher in the 800-meter run in 1912, Edmundsons track experience would heavily influence how he coached basketball.

At the time of the 1912 Games, Edmundson was 26, born Aug. 3, 1886, in Moscow, IDA., and a 1910 graduate of the University of Idaho (he received his degree in agriculture), for which he ran the quarter-mile, half-mile and one-mile runs, usually all in a single meet.

He captained his college track team, won a national 800-yard title in 1909 in a meet held as part of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle — and also played basketball.

It was as a boy in the Palouse region of western Idaho that Edmundson acquired his nickname. While training on dirt roads outside of Moscow, Edmundson frequently muttered Ah, heck! in self-debasement of his efforts.

Amused, his mother began calling him Hec. Scores of UW athletes over four decades lengthened that to Uncle Hec, a friendly sounding nickname that stood in contrast to the usual Edmundson demeanor.

An incessant gum chewer, Edmundson almost always wore a poker expression, but had great affection for his players: He loved to paper the walls of his office and den with photographs of athletes he had mentored.

Following the 1912 Olympics, Edmundson departed the Palouse and began his coaching career with the Texas A&M track and field team. After one season, he returned to Idaho and coached track, cross country (Edmundson had organized Idahos first cross country team in 1908) and basketball before becoming Washingtons track coach (and football trainer) in 1919.

Two years earlier (1917), Edmundsons Idaho basketball team had played defense with such ferocity that sports writers often said that it vandalized its opponents.

In 1917, Harry Lloyd McCarty, a sports writer for the student newspaper, The Argonaut, felt compelled to say, The opening game with Whitman will mark a new epoch in Idaho basketball history, for the present gang of Vandals have the best material that has ever carried the I into action.

Two years later, Idaho athletic officials officially adopted Vandals as the school’s athletic nickname.

After arriving in Seattle with wife Mary (Zona), it took Edmundson only a year to produce his first Olympian, August Gus Pope, a bronze medalist (discus) in Antwerp, Belgium. A year after Pope became the first UW student to earn an Olympic medal (1920), Edmundson, at the urging of athletic manager Darwin Meisnest, replaced Stub Allison as the schools basketball coach.

In those days, when long road trips made little economic sense for conference schools, the newly formed Pacific Coast Conference was segregated into northern and southern divisions, the main reason why Washington made only four trips to Los Angeles between Edmundsons first year (1921) and 1957, three years after his retirement.

Edmundsons Huskies owned the Northern Division, claiming 12 titles, including five straight from 1928-32, with six runner-up finishes. His teams won 20 or more games a school-record 11 times, including 25 or more four times, helping Edmundson amass a career record of 488-195 (.714), more than double the number of victories posted by any other UW head coach (Harshman).

Between his first year, 1921, and 1940, Edmundsons Huskies had 19 consecutive winning seasons. During that span, Washington lost more than 10 games just once (15-11 in 1937).

Not only did Edmundson experience just one losing season in 27 years, he remains the architect of seven of the 10 longest winning streaks in UW history, including a 26-game run from Feb. 14, 1938 to Jan. 21, 1939, the first year of the NCAA Tournament.

Edmundson had his three best teams in 1931, 1936 and 1943. The 1931 club featured guard Ralph Cairney, went 22-3 and was rated, in the absence of a postseason tournament, by noted sports historian Alexander Weyand, the nations second best behind Northwestern.

Edmundson’s 1936 Huskies (25-7) won four of five games at the U.S. Olympic Trials (see Wayback Machine: UW Bonznza At The 1936 Olympics), and a loss to national AAU champion McPherson at Madison Square Garden in New York City prevented Edmundson from sending seven of his players to the Olympic Games in Berlin, the major perk for winning the trials (as it was, Washingtons Ralph Bishop made the Olympic roster, the only collegian selected).

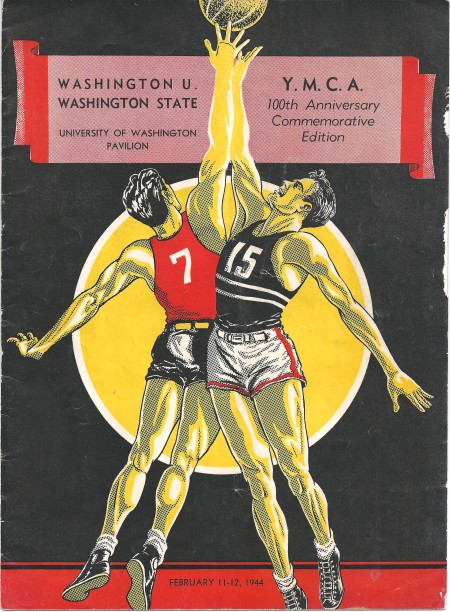

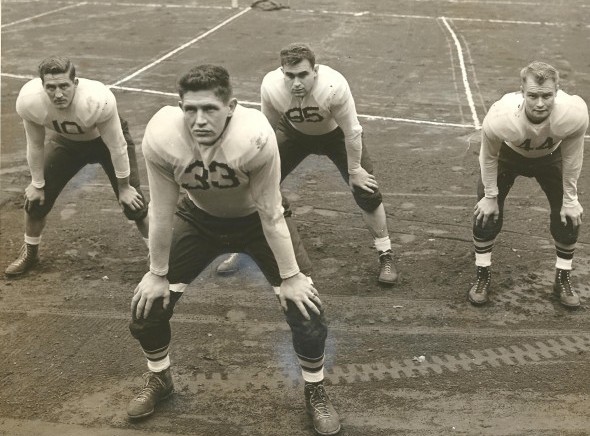

Washingtons 1943 team, led by All-America guard Bill Morris, went 24-7 and became the first in school history to play in the NCAA Tournament (lost to Texas and Oklahoma at the West Regionals in Kansas City).

Part of the reason for Edmundsons success as a basketball coach — a big part of it had to do with the up-tempo style of play he developed. That style enabled 29 of Edmundsons players, most notably Harold McClary (1929), Henry Swanson (1930-31), Hal Lee (1933-34), Bob Galer (1934-35), Jack Nichols (1944, ’47-48) and Sammy White (1948-49), to be named All-Northern Division.

In his first years at UW, Edmundson practiced with his players (Harshman did the same thing as a young coach at Pacific Lutheran) so that he could get them to buy into his basket-a-minute philosophy. The more you run, and the faster you run, the more you win, Edmundson told a Seattle Times reporter in the early 1920s.

Edmundson also taught his players how to shoot a one-handed jump shot. Although he always denied inventing the shot, Husky players used it with great success long before Stanford All-American Hank Liusetti made it famous in the 1950s.

In this way, Edmundson transformed what had been a traditionally low-scoring team into a comparative barn-burer. The year before Edmundson became coach (1920), the Huskies scored fewer than 40 points 14 times in 15 games. By 1931, UW scored 40 or more 15 times in 28 games.

Edmundson, also in his earlier years, frequently raced against his athletes during track and field practices. “I ran against them in every event outside the hurdles, and won them all, Edmundson once said.

His track teams won eight Northern Division championships, three PCC titles and five times finished among the top five schools at the NCAA Championships, including second in both 1929 and 1930.

Edmundson coached seven NCAA champions: Gus Pope (1921, shot and discus), Jim Charteris (1925, 880), Herman Brix (1927, shot), Rufus Kiser (1928, mile), Steve Anderson (1929, low hurdles; 1930, high hurdles), Paul Jessup (1930, discus) and Eddie Genung (1931, 880).

As a track coach, Edmundson experienced no better day than June 15, 1930, except for perhaps Aug. 23, 1930.

On June 15, at the NCAA Championships at Stagg Field in Chicago, Anderson matched the world record in the high hurdles with a clocking of 14.4 and finished third in the 220-yard low hurdles. Jessup set an NCAA record in the discus with a throw of 160-9 3/8.

On Aug. 23, at the national Amateur Athletic Union meet held on the campus of the University of Pittsburgh, Anderson again matched the world high-hurdle mark at 14.4 while Jessup shattered the world record in the discus by more than eight feet, heaving it 169-8 7/8. Meanwhile, former Husky Genung won the 880, setting an American record in 1:53.4. Yet another former Husky, Brix, whom Edmundson had also coached (1927-28), set an American record in the shot put at 52-5 ¼.

(On only one other occasion has a Husky track team come close to matching that performance in a national meet. On May 25, 1963, at the Modesto (CA.), Relays, UW pole vaulter Brian Sternberg set a world record with a leap of 16-7, and long jumper Phil Shinnick set a world record with a mark of 27-4.)

Edmundson brought to Washington more than coaching acumen. He had ideas. A year before he accepted a job at Washington (1918), Edmundson originated a state high school basketball tournament in Idaho. Five years later (1923), he talked over the idea of starting a state tournament in Washington with Husky baseball coach Tubby Graves.

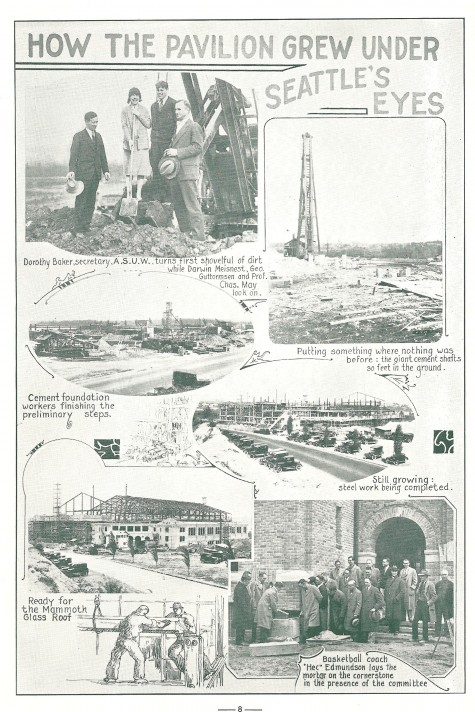

Together, they were able to get athletic manager Darwin Meisnest to go along with their idea provided that Edmunson and Graves funded the tournament out of their own pockets.

Edmundson organized the first state tournament essentially by postcard. He got high school coaches from around the state to send him postcards that listed the reasons why their teams should be picked to play in the tournament. Edmundson sorted through the cards and made his choices. The tournament became so popular that the state high school athletic association took it over in 1928.

Edmundson also originated the hands-in-the-huddle, or five-man handshake,” still in use by basketball teams as they take the floor just prior to tip-off.

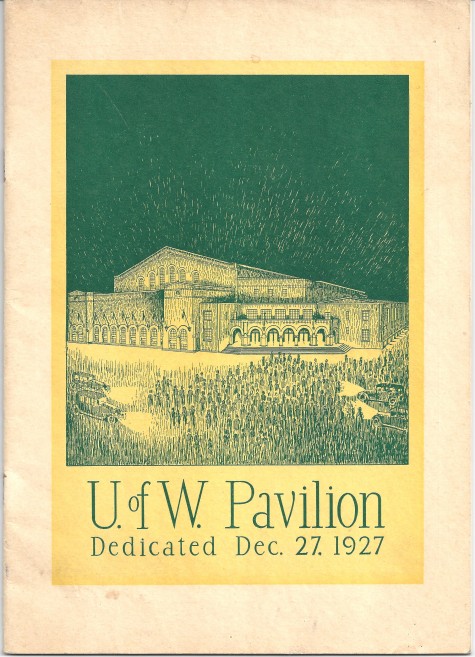

Edmundson, who helped Meisnest raise funds to cover the cost of construction of the Washington Pavilion — which the school dedicated on Dec. 27, 1927 with a 34-23 victory over Illinois — had a bittersweet end at Washington.

In 1947, he briefly pondered retiring as basketball coach, then decided to remain at least one more year, perhaps two. Having made that decision, Edmundson was shocked to receive a message from Cassill, the athletic director, to the effect that Cassill appreciated Edmundsons carefully worded letter of resignation (Cassill fired football coach Ralph Pest Welch in a similar fashion).

Edmundson had just come off a 16-8 season, his 24th such campaign, and there had been no rumblings of discontent around the program. Further, Edmundson had become a prominent member of the NCAA Mens Division Basketball Committee. His work on that committee had helped persuade the NCAA to award two Final Four tournaments (1949, 1952) to the University of Washington.

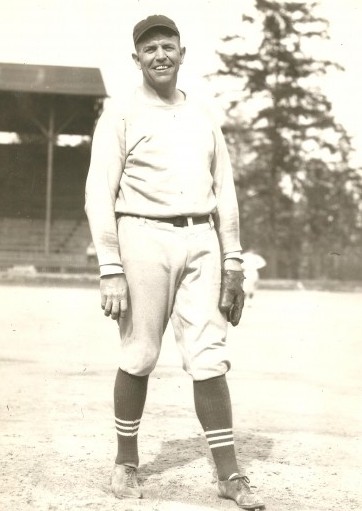

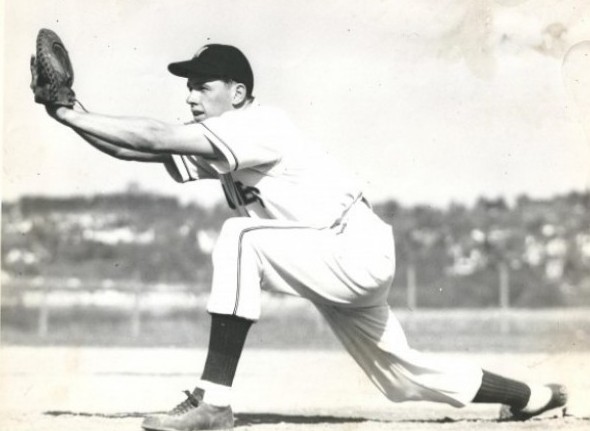

But Cassill simply wanted a new coach, and found him in Art McLarney, a Port Townsend native who played major league baseball with the New York Giants (1932) and had a two-year stint with the Seattle Indians (1933-34). A Washington State graduate, McLarney came to Washington in 1946 as an assistant coach assigned to both football and basketball.

A year after Edmundson’s axing (Jan. 16, 1948), and after Cassill admitted he had made a mistake in letting Edmundson go and apologized, UW officials renamed the Washington Pavilion Hec Edmundson Pavilion.

Edmundson continued to coach the track program through 1954, at which point he retired. The Helms Foundation inducted him into its Hall of Fame twice, first for his basketball career, then for track.

The University of Idaho named one of its athletic facilities after him. Idaho also annually awards the Hec Edmundson Trophy to the schools outstanding athlete. Every year since 1934, Washington has given the Hec Edmundson award to its most inspirational basketball player.

Edmundson liked to say that one of his favorite moments occurred May 28, 1954, shortly after his retirement (March 20, 1954), when nearly 400 of his former athletes came from all over the United States to salute him at a testimonial dinner at the Olympic Hotel, an event organized by former hurdler Steve Anderson.

But the top moment of Edmundsons career occurred March 24, 1943, when one of his former basketball players, Bobby Galer, a 1935 All-American, received the Congressional Medal of Honor from President Franklin D. Roosevelt for conspicuous heroism and courage above and beyond the call of duty as leader of a Marine fighter squadron in aerial combat with enemy Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands during World War II.

Edmundson, who worked as a state athletic commissioner in the Art Langlie administration after leaving UW, suffered his first stroke, a relatively minor one, in January of 1960. But he never fully recovered and was forced to move into a nursing home near the UW campus.

On Aug. 5, 1964, the 78-year-old Edmundson was admitted to Swedish Hospital after suffering another stroke. One day later he died.

During his time at Washington, Clarence “Hec” Edmundson outlasted seven school presidents (from Henry Suzzalo through Lee Paul Sieg), seven athletic directors (from Meisnest through Al Ulbrickson), and six football coaches (from Allison through Howie Odell).

One other way to look at the long impact that Edmundson had: If current head coach Lorenzo Romar doubled his UW victory total (197), he would still be nearly 100 wins shy of matching Edmundson’s 488.

Edmundson is buried at Calvary Cemetery, about one mile north-northeast of the pavilion that bears his name.

———————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive.David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com

8 Comments

Great article. There’s actually an even more obscure known fact of Marv Tommervik being drafted as the 183rd pick by the Philadelphia Eagles in the same NFL draft as Harshman.

Great article. There’s actually an even more obscure known fact of Marv Tommervik being drafted as the 183rd pick by the Philadelphia Eagles in the same NFL draft as Harshman.

Great to know the complete background of a historic UW coach & legend where I spent so many of my 4 years practicing in our pavilion named after him, Hec Ed, thanks David,

Ray Price

the Machine

Husky Basketball & Baseball ’74

Great to know the complete background of a historic UW coach & legend where I spent so many of my 4 years practicing in our pavilion named after him, Hec Ed, thanks David,

Ray Price

the Machine

Husky Basketball & Baseball ’74

dood they got us smoak. he’s hitting like 370 in september. back off.

Front Office: Get rid of Chuck and Howie yesterday, find baseball man to run franchise

Zduriencik: Keep him. Only GM with long-term vision we’ve EVER had.

Starters: 1 (Felix and Vargas fine, rest okay while Big Three hopefully mature on farm)

Bullpen: 2 (Good arms, but overworked)

Infield: 2 (Less than meets the eye, except for Seager)

Outfield: 2 (Still more questions than answers, need more power)

Catcher/DH: 1 (Start ’13 with Olivo, but bring in Zunino ASAP when he’s ready)

EXTRA

Radio/TV: Send Sims to Seahawks to replace Raible, move Rizzs to TV booth and get a REAL lead announcer for radio (Scully wannabes like Wilson need not apply)

Mascot: Put Moose head on plaque and bring up Vinny Venado from Mazatlan (trust me…he’s hilarious)

Tickets: Try having a WINNING season before increasing prices. You won’t draw more flies by simply raising the price of garbage.

Would you make serious changes in the front office/owners? Yes or no.

—YES!!! New ownership that is local. Keep Jack Z and Wedge.

Are you willing to ride with general manager Jack Zduriencik? Yes or no.

—Yes. Wish this year was a little better but he has another 1 or 2 more years to get us to a World Series. Yes, I said WS. The fans deserve that drastic of a demand for a better part of 35 years being a laughing stock.

Has manager Eric Wedge done enough to stick around? Yes or no.

—Yes. Next year is do or die.

Starters Option 1: Stay the course. Option 2: Go outside the organization.

—-Trick question. We need to stay the course but also get some key trades and free agents. Keep Felix, Vargas and Iwakuma.

Bullpen Option 1: In over its head. Option 2: Tired at the end of a long season.

—-Tired of the season. So far out of it. Checked out.

Infield Option 1: Growing pains were expected. Option 2: Expectations were excessive.

— 1. Growing pain were expected.

Outfield Option 1: Gutierrez will be healthy, and he and Saunders will anchor the outfield. Option 2: Look elsewhere.

— Keep Saunders. Keep an eye on Guti. Make some key trades and free agents.

Catcher/DH Option 1: Olivo at minimal cost to go with Montero and Jaso. Option 2: Bring Zunino in with Montero and Jaso.

—Dump Olivo. Option 2!!!!! Between Zunino, Montero and Jaso you can figure out C, DH and even 1B options.

No option: Nov. 6, vote.

This player, that player, this bullpen arm, that lame outfielder, this prospect, that prospect – what does it really matter? Nothing matters as long as the execrable duo of lincoln and armstrong are in place, and by extension, that no-show hermit recluse owner. Hickey said it best: the fan vote is already in. The last game I attended, a couple of weeks ago, that mutt Noesi started, and we were out of the game by the middle of the first. it was an empty, listless, dreary experience. It’ll be a long time before I set foot in that park again.