By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

From the dignified, derby-topped Dan Dugdale at the dawn of the last century to Eric Wedge today, the men who have directed Seattles numerous professional baseball enterprises we count 56 spanning the Siwashes through the Mariners — represent remarkable managerial diversity.

The 56-man cast includes iconic figures (Fred Hutchinson), tyrants (Rogers Hornsby), good-ol’ boys (Joe Schultz), Hall of Famers (Bob Lemon), ball busters (Dick Williams), pushovers (Bill Plummer), old-school guys (Darrell Johnson), surfer dudes (Rene Lachemann), major mistakes (Luke Sewell, Maury Wills), borderline geniuses (Jack Lelivelt), and at least one coulrophobiac (Bob Melvin, fear of clowns).

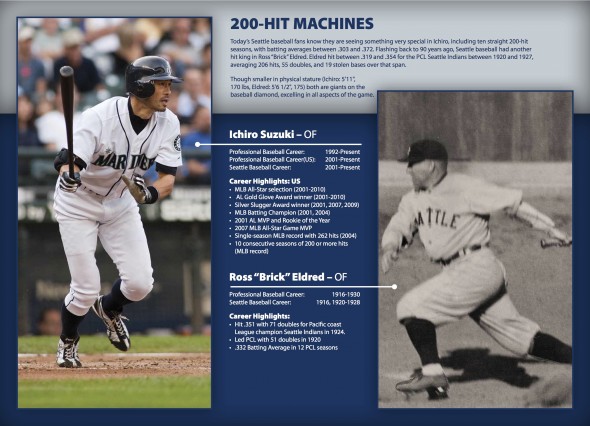

The Mariners, who have employed at least one skipper of every description, offer a delightful exhibit at their Safeco Field Museum titled Connecting The Generations. It links, in words and stunning photographs, baseball now and then.

Wayback Machine featured two images from the collection in recent weeks (a third appears below). Crafty Pitchers is a side-by-side comparison of Kewpie Dick Barrett, the all-time wins leader for the Rainiers (see Wayback Machine: “Kewpie” Dick And The Rainiers) and Jamie Moyer, the all-time wins leader for the Mariners.

Five-Tool Players is a pairing of Ken Griffey Jr. (Mariners) and Jim Rivera (Rainiers) that we published last week (see Wayback Machine: Rajah, Rivera, 51 Rainiers).

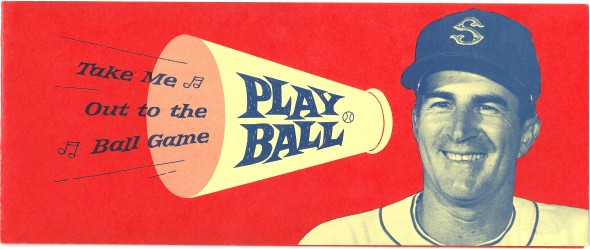

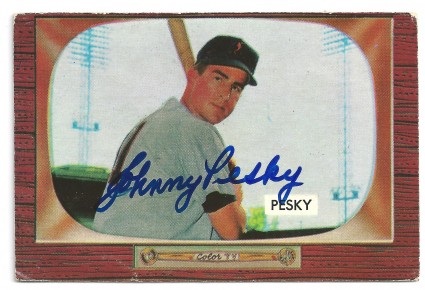

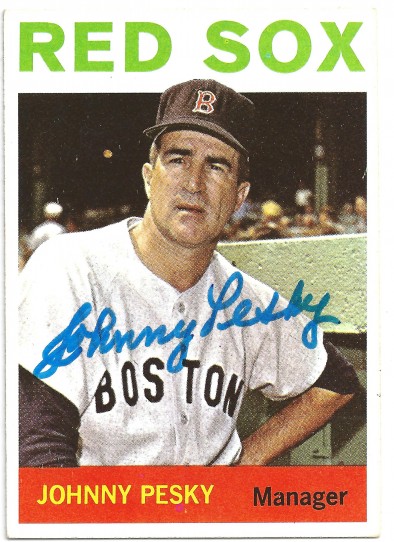

If the Mariners ever opt to augment Connecting The Generations, they could do worse than a Firery Managers or Colorful Characters display with Lou Piniella representing this generation, Johnny Pesky the long ago.

Like Lou, Pesky had a passionate baseball outlook and flammable temper. Like Lou, Pesky often wrangled with umpires. Like Lou, Pesky inspired adulation and debate among the public. Like Lou, many Pesky whims became headlines in the next days newspaper.

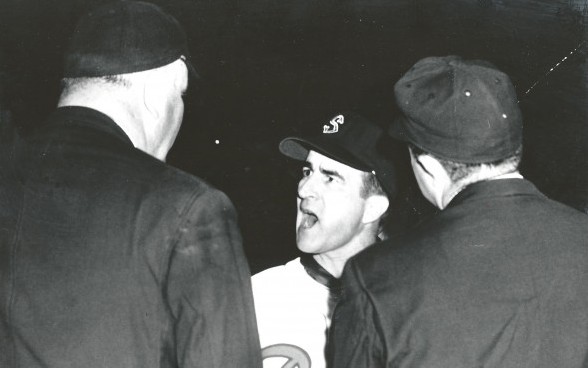

Enough generalities. A few days after the events of June 28, 1962, the Pacific Coast League slapped a $50 fine on Pesky for an astonishing act of baseball impudence: During a game against the Salt Lake Bees, Pesky went nose-to-face mask with plate umpire Dick Lifrieri following a ruling Pesky deemed particularly flawed.

During the exchange, Lifrieris mask kept striking Peskys lower lip as Lifrieri nodded vigorously while expressing his points. Irked by Lifrieris damaging head bobs and desiring to get his own nose closer to Lifrieris, Pesky ripped Lifrieris mask off and tossed it.

After the PCL docked Pesky $50 for his brazenness, the Seattle manager complained that Lifrieris mask had bruised his lower lip. The PCL lowered the fine to $25. But Lifrieri countered that Pesky had argued with chewing tobacco in his mouth, and had spewed noxious juice on his face. The PCL reinstated the $50 fine.

Let’s re-set the Wayback controls to May 17, 1994. That day, during a joust with Kansas City, Piniella kicked his cap what is believed to be a Mariners record 16 times, depositing four loads of ballpark alluvial on home plate for good measure.

Re-set the controls again to Aug. 26, 1998, when the Mariners engaged the Cleveland Indians. After Piniellas fifth kick of his cap, broadcaster Dave Niehaus told his audience, He got some distance on that one! That was a three-pointer right there!

Re-set to Sept. 18, 2008, when the Mariners hosted Tampa Bay. After Piniella uprooted bases, flung bats, and kicked up a dirt storm following a botched call by the evenings buttinski, umpire C.B. Bucknor, bench coach John McLaren remarked, That was the best. Lou had all of his greatest hits in it.

A few days later, a reporter showed Piniella a photograph of him kicking his hat. Noted Lou, a twinkle in his eye: Im going to send that to Jon Gruden (then coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers). Im ready for the season. Thats good form there.

Page 181 of “The Great Book of Seattle Sports Lists” ranks Pinella’s greatest outbursts. It’s titled “Nobody Do The To-Do Like Lou Do.” Oh, yeah? How about the events of June 29, 1961, Rainiers vs. Tacoma Giants?

Before that entertainment ended, every Rainier, every Giant, each coach, both managers and three umpires had engaged in a 48-person tableau of jostling, tussling, rib-cage jabs, face smacks, and eyeball pokes, to the delight of 4,679 Sicks Stadium customers.

In the second inning, Eddie Fisher, Tacoma pitcher, plunked Lou Clinton, Seattle batter. Clintonevidently made a mental note. With Fisher still dealing in the fourth inning, Seattles Tommy Umphlett bopped a homer to tie the game 1-1.

Clinton came up next, and Fisher immediately whistled his first pitch, a fastball, past Clintons ear and into the backstop screen. Infuriated, Clinton waved his bat threateningly and charged the mound. But before Clinton could take out Fisher, 5-foot-9, 168-pound Johnny Pesky hurtled out of his third-base coaching-box perch and pancaked the 6-2, 210-pound Fisher with an NFL-worthy sack, a signal for both benches to empty.

“Somebody had to do something,” said Pesky, his nose unscathed but sporting a welt under his right eye.

Lou Piniella ranted, raved, kicked and cursed, but never, to the best of our knowledge, did he ever sack the opposing pitcher as Johnny Pesky did — although he did wrestle one of his own, Rob Dibble, in Cincinnati in 1990.

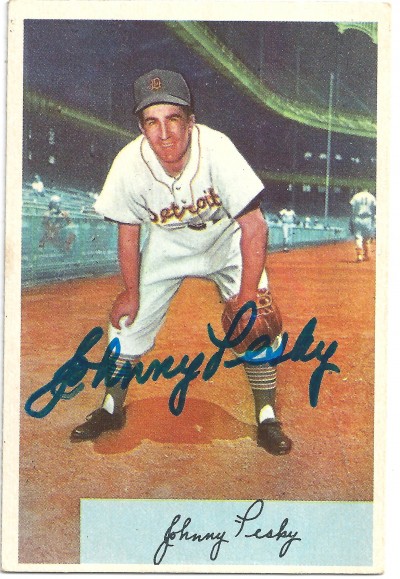

We are, of course, talking about that Johnny Pesky: all-time Red Sox legend; with Bobby Doerr, part of one of the great double-play combos in baseball history; goat of the 1946 World Series; the man after whom the right-field foul pole at Fenway Park is named; a guy referred to as Old Needlenose as often as he was Pesky, which wasnt his real name anyway.

Piniella spent a memorable decade in a Seattle dugout, Pesky only two seasons, and wouldnt have spent any if the ownership of the Rainiers hadnt passed from Emil Sicks hands Oct. 15, 1960, and into those of Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey.

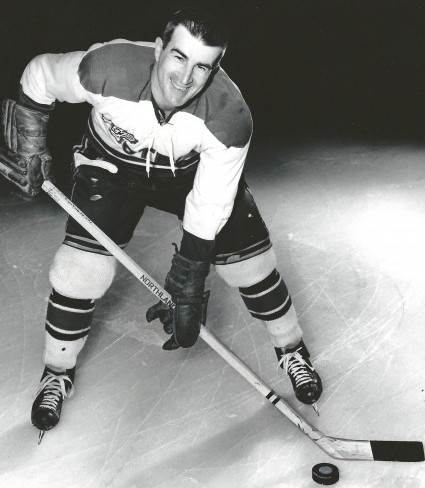

That development set into motion Peskys first visit to Seattle since a 1936 decampment when, as an accomplished skater and stick handler, he accompanied his amateur hockey team from Portland to the Seattle Ice Arena for a game against a local squad.

The contest probably would have been lost to history had not one of Peskys teammates, Joe Erautt (who later played for the Rainiers), been knocked out by a Seattle fan with the butt end of an umbrella, a bit of mayhem newspapers found too compelling to ignore.

Johnny Pesky was not yet Johnny Pesky when Erautt was felled by the umbrella, and wouldnt be until 1947 when he legally changed his name, explaining, trying to decipher four syllables is tough, especially for me.

When he squalled into a section of northwest Portland known as Slav Town Sept. 27, 1919, his parents, father Jakov and mother Marija, Dalmatian immigrants, christened him John Michael Paveskovich. He arrived, he would say later, with an already oversized nose.

By his middle teens, the youngster who would become Johnny Pesky had taken to hanging around the Portland Beavers ballpark, a few blocks from the Paveskovich home, at NW 23rd and Vaughn Street.

Johnny caught the eye of Vaughn Street Park groundskeeper Rocky Benevento, who put him to work cleaning dugouts, bullpens and the ballparks laundry room, where young Coast Leaguers such as Ted Williams came to wash out their uniforms.

Pesky played all infield positions except first for Portlands Lincoln High School and, following graduation, got in some games for the Central Oregon Bend Elks and Silverton American Legion team, just north of Salem. While toiling for Silverton, he began to attract the attention of major league scouts.

The Bend and Silverton clubs had associations with local timber outfits, and one, the Silver Falls Timber Co., happened to be owned by Yawkey, whose timber dealings aided his acquisition of the Red Sox.

The Cardinals offered Pesky a $2,500 signing bonus, but Red Sox scout Earl Johnson, a Ballard High graduate who pitched for Boston (see Wayback Machine: Baseballs Most Intriguing Brother Act), so impressed Peskys mother, Marija, that Johnson signed Pesky for a $500 bonus, with the promise that Pesky would receive an additional $1,000 if he remained in the Red Sox organization for two years.

The Red Sox started off Pesky in 1940 with Class B Rocky Mount of the Piedmont League, where he made $140 per month, and promoted him in 1941 to the AA Louisville Colonels of the American Association. Pesky hit .325 with 195 hits in 146 games and won the league’s MVP award.

Pesky reached the majors the following year at 22, making his debut April 14 against Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. He hit second behind Dom DiMaggio and just ahead of Williams, both of whom, along with fellow Oregonian Bobby Doerr, would become life-long friends.

Wearing No. 6 he loved the symmetry of No. 6, the scorers number for the shortstop — Pesky held up his part in the top of the Boston order, going 2-for-4 to DiMaggios 1-for-3 and Williams 3-for-4.

Pesky produced 70 multi-hit games that year, had eight four-hit games, went 5-for-5 against Virgil Trucks and the Detroit Tigers June 13, and probably would have won the Rookie of the Year award had it existed.

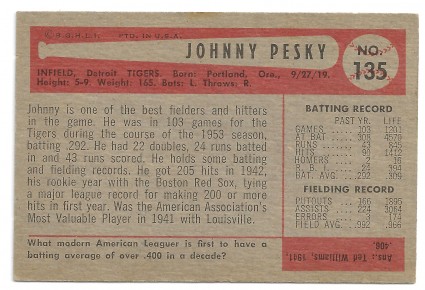

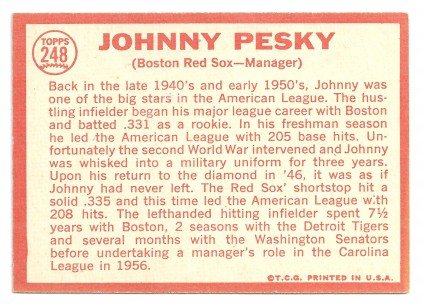

He hit .331 in 147 games (second in the AL to Williams .356) and his 205 hits, an AL rookie record, led the league. MVP voters placed him third, behind Joe Gordon and Williams. For all that, Pesky made $4,000.

As SABR (Society For American Baseball Research) pointed out in an essay on Pesky, the unparalleled start to his major league career could have propelled him into the Hall of Fame had World War II not pulled out three prime years (1943-45).

When he came back (from the Navy), he twice more produced over 200 hits, in the Red Sox pennant-winning year of 1946, and in 1947. Had Pesky managed 200 hits for each of his three missing years, there is every possibility this lifetime .307 hitter could have made the Hall.

Peskys almost Hall of Fame career included an All-Star appearance in 1946. He led the AL in hits three times (1942, 1946-47), in runs six times (1942, 1946-50), ranked in the top 10 in on-base percentage six times, and batted .330 or higher three times.

One year, Pesky led Williams in the batting race for six weeks. This might be his most remarkable single-game achievement: On May 8, 1946, in a 14-8 Boston win over the White Sox, Pesky went 4-for-5 and was the first AL player to score six runs in a nine-inning game.

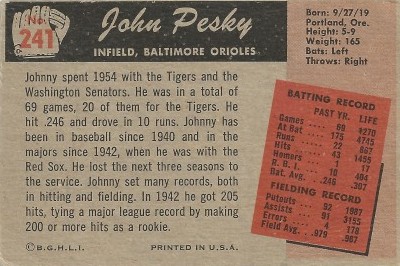

During Peskys 10 years with the Red Sox, he became such a part of the Boston fabric that he figured he would remain associated with the club for the rest of his life (he settled in Lynn, MA.) until the Red Sox, in a multi-player swap with Detroit, sent him to the Tigers June 3, 1952.

Dismayed over the trade, Pesky played three years in Motown and finished his career with the Washington Senators in 1954.

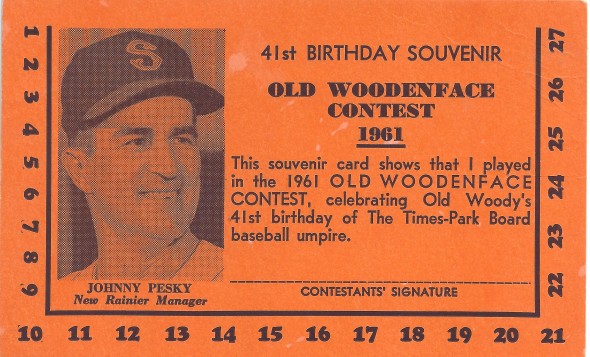

Pesky began coaching in the Yankees system with the 1955 Denver Bears of the AAA American Association. He returned to the Detroit organization and, from 1956 through 1960, bounced among various Tigers subsidiaries: Durham Bulls (Carolina League, 1956), Birmingham Barons (Southern Association, 1957), Lancaster Red Roses (Eastern League, 1958) and Knoxville Smokies (South Atlantic League, 1959). In 1960, Pesky managed the AA Victoria Rosebuds (Texas League), another Detroit affiliate.

The machinery for Peskys return to the Red Sox went into gear when Yawkey bought the Rainiers from Sick and moved Boston’s AAA operation from Minneapolis to Seattle.

Shortly after the Red Sox fired farm director Johnny Murphy and replaced him with Neil Mahoney, Mahoney, a friend of Peskys for 20 years, offered Pesky the Rainiers job.

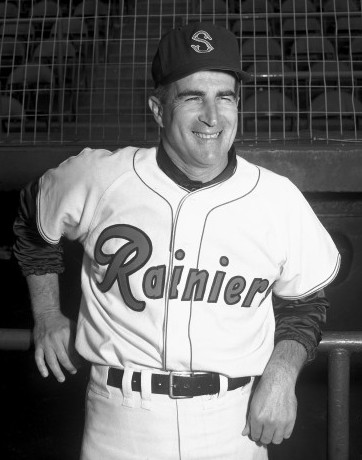

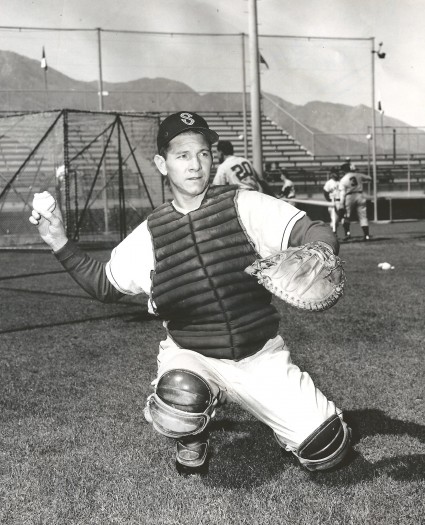

I accepted so fast Neils head swam, said Pesky, who officially became skipper Oct. 18, 1960, replacing Dick Sisler, who had gone 77-75 in the final year of Sicks ownership.

Im so delighted that words cant describe it, Pesky told Seattle reporters. This is my first shot as a AAA manager and, believe me, Ill make the most of it.

Peskys aim: succeed in Seattle and earn a shot at managing his beloved Red Sox. Pesky never made a secret about his ambition, although he recognized the irony of the pursuit.

What it amounts to, I guess, Pesky told Hy Zimmerman of The Seattle Times, is that you spend your entire life striving for the least-secure job youll ever hold.

Pesky awed the Seattle press. At every opportunity, he gathered the baseball writers in coffee shops and watering holes and, dragging on an ever-present cigar, told tales into the late mornings and wee hours.

The writers, in turn, wrote glowingly of Pesky, conveying to Rainiers fans their impression that Pesky bordered on managerial genius.

The Rainiers have an excellent baseball man, Zimmerman wrote more than once.

Seattle baseball scribes, Zimmerman chief among them, penned dozens of columns on Pesky without ever mentioning his given name, merely identifying him as Needlenose, or “Old Needlenose,” a tag Williams had pinned on him in their Boston playing days. Pesky didnt mind the jibe, often poking fun at the schnoz he packed through life.

Pesky Paveskovich, as the baseball writers also called him, loved to talk baseball, and just about everything else, for that matter. He even told stories on himself, not all flattering, such as the one that played out in the 1946 World Series between Boston and St. Louis.

In the eighth inning of Game 7, score 3-3 and Enos Slaughter of the Cardinals on first, Harry The Hat Wallker stroked a low fly over Pesky into left center. As Leon Culberson fielded the ball, Slaughter streaked past second and headed for third.

After the relay from Culberson, Pesky glanced at Slaughter, debating whether he would break for the plate. In that instant of hesitation, Slaughter indeed bolted for home.

Pesky threw too late. Slaughters run, which went down in history as “The Mad Dash” — won the game and the Series.

That put me in the company of Mickey Owens and a lot of other famous goats of the World Series, Pesky told Zimmerman.

I was accused of holding the ball. For weeks, everywhere I went people asked me what happened. At first, I joked that I wanted to make sure I was in a National League park, so I looked at the signature of the ball. Sure enough, it was signed by Ford Frick (then president of the National League).

Nine weeks after Pesky certified himself an historic goat, he visited his sister in Portland.

Everywhere I went, everybody had something to say about Pesky holding the ball,” Pesky explained. “My wife and sister and I went to the Oregon-Oregon State football game. It was a sloppy, rainy day. All through the first half, there was a lot of fumbling. At halftime, I went out and got some coffee.

When I came back, a drunk sitting behind us tapped me on the shoulder. I turned around and he said, Pesky, ya bum. What are you doing here? Why did you hold that ball?

My wife was upset. She thought we ought to move to some other seats. I told her, No, Im a pro. Ive got to take it. If we were back in Boston, Id be hanging (in effigy) in the square.

In the second half, Oregon State kicked off, Oregon fumbled and recovered. Then Oregon fumbled and Oregon State recovered. The drunk jumped up onto his seat and yelled, Give the ball to Pesky! He knows how to hold it!

Another time, Pesky confided hard to tell what prompted his outburst of candor to Georg N. Myers of the Times that beneath his uniform he always wore Red Sox red boxer shorts.

Theyre warm, comfortable and easy to take care of, Pesky said. I live in a hotel room. I wash ’em every night, and I always wash ’em out in pink shampoo.

Pesky had a great story he told several times about Yogi Berra, the Yankees catcher celebrated for his droll stroll through lifes perplexities.

So Red Jones is umpiring and having trouble with Yogi, Pesky related. Yogi squawks on strike one, then on strike two, and then says to Jones, One more like that and Ill bite off your head. You do, answered Jones, and youll have more brains in your stomach than in your head.

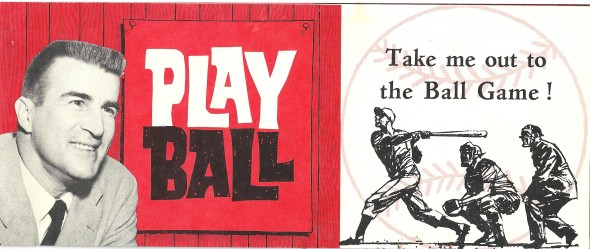

When, in early 1961, Pesky made his first visit to Seattle since Erautt got whacked with the umbrella, he attended a Puget Sound Sportscasters and Sportswriters luncheon, his official introduction as manager. When he strode to the microphone, Pesky opened with:

Im aiming for a club with tremendous pitching, real good defense and a lot of power.

Such fanciful ambition drew chuckles from the crowd, and then Pesky got right to the point:

Im a tyrant when it comes to conditioning,” he said. “A leaner horse runs faster than a fat one. And forget all this stuff about hustle. Ill take hitting and pitching. Spirit? Anyone hitting .320 or knocking off those wins on the pitching mound is spirited.

When players make mistakes, they will hear about it quickly. There will be no pampering. We are out to win ball games, and we will win ball games, and Im the boss. My belief is that a player remembers a kick a lot longer than he does a pat.

Asked by one writer to confirm reports that he had been known to run his players through rigorous drills early in the morning following night games, Pesky said, You find a lot out about your players that way.

Asked by another what difference he expected to make as manager of the Rainiers, Pesky replied, A manager may make a difference of four or five games over a season. And if they are the right four or five games, the manager becomes a genius.

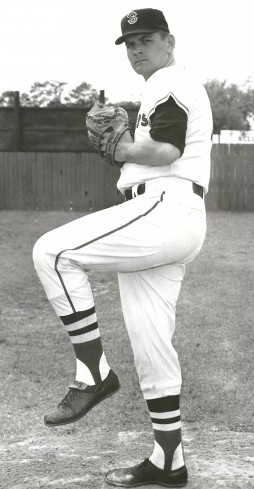

Quizzed about the Rainiers roster, Pesky talked up several players. When he got to Dick Radatz, a 6-6, 230-pound right hander who figured to work out of the bullpen, Pesky didn’t answer, but asked, How does someone grow that big in only 24 years?

After watching Pesky orate, Zimmerman wrote, He is shorter than you imagined, younger looking. He has black-button eyes under a bristle of black brush that cant muss. His speech is sidemouth. He is fast of phrase, but quick of ear. Pesky is decisive, bold, but sound. He despises defeat. He plays to win today; next week is a long way off.

Six weeks after regaling Seattle media, Pesky took the Rainiers to spring training in DeLand, FL., promising a contending team if Boston held up its part of the bargain: furnish the Rainiers with the right ingredients.

By the time spring shook out, Pesky had a ball club whose most notable players included future big leaguers RHP Earl Wilson, Radatz, RHP Galen Cisco, OF Lou Clinton, RHP Don Schwall, INF Harry Malmberg and RHP Jay Ritchie, as well as OF David Mann.

Two years earlier, July 31, 1959, Wilson made his MLB debut, in the process becoming the first black to pitch for the Red Sox. Seattle baseball writers asked Pesky if, uh, Wilson’s “color” might be a problem.

“I’ll pitch him whenever I want and the hell with what anybody thinks,” Pesky responded.

Wearing Man in Space patches on their sleeves to publicize the upcoming Century 21 Exposition (Worlds Fair), the Rainiers split their opening doubleheader with San Diego April 20. After that, they struggled, but finally moved into first place in late May, when Radatz provided one of the seasons most amusing moments.

During a road trip to Hawaii, he fell out of the bullpen cart while en route to the mound.

Got my foot caught somehow, he explained. I was so embarrassed I felt like a penny waiting for change.

The Rainiers spent more than two months in first before they began heading south, a consequence mainly caused by Bostons extraction of Seattles three best pitchers, Schwall, Cisco and Arnold Early.

When the pitching departed, the batters had to shoulder the burden. But that shoulder sagged. The Rainiers lost their snap, and all Pesky could do was gulp down his disappointment.

I may have become spoiled during our league-leading days, said Pesky. I mistook development of rookies for genuine strength. I blame myself. You know, this league is stronger than I figured. I also guessed wrong on a couple of guys. They werent ready for this stuff.

The Rainiers were, however, ready for the Portland Beavers Aug. 27, when one of the great novelty acts in the city’s professional baseball history occurred, an appearance by the ancient Satchel Paige, who tossed four frames in the second game of a doubleheader (see Wayback Machine: Satchel Paige In Seattle) won by Seattle.

When the season ended (Rainiers in third), Pesky gathered Seattles baseball writers. In advance, Pesky told them he wanted to take his share of the blame.

Down at San Diego, Pesky said, we had a three-run lead in a game with a time limit on it, because we had to catch a plane. The pitcher was in tough. Dick Radatz and Jay Ritchie were warming up. I had my choice. In my heart, I knew Radatz was the man. But I wanted to see what Ritchie would do in a spot like that. San Diego got a homer and beat us. The worst of it was, everybody on the team knew I had booted it.

Another time, were five runs down against Spokane. Bob Tillman is on third. A pop sailed out between the shortstop and center fielder, and neither one could pick it up. I know Tillman cant run. But I sent him home anyway. He was out by 15 feet. We lost 11-10 because of the run I squandered.

In the next days Times, Zimmerman wrote, Johnny Peskys heart is as big as his nose.

Much as Pesky wanted the Boston job, he felt he needed another year at the AAA level. Record-wise, it didnt turn out well. The Rainiers fell out of the race by suffering 23 defeats in 28 games. Injuries were a part of that, but so was his roster: his 1962 pupils did not have the scholastic background for the AAA curriculum, finishing in fourth place.

Every day was a joust for survival, Pesky said.

One of the more lively events of an otherwise ho-hum year occurred in May when the Red Sox sent pitcher Tracy Stallard to the Rainiers who, in conjunction with World’s Fair promoters, saw a chance for widespread publicity.

A year earlier, Stallard had surrendered home run No. 61 to Roger Maris. Fair officials announced they would fly in a Brooklyn kid, Sal Durante, who had caught Maris’ 61st homer in the stands at Yankee Stadium, and pay him $1,000 if he could catch a ball dropped by Stallard from the top of the Space Needle.

The stunt never came off, determined to be too dangerous. Durante did, however, snag a few balls tossed by Stallard from atop a nearby Ferris wheel.

The Rainiers mid-division finish didnt hurt Pesky’s chances with Boston. Shortly after the 1962 season ended, Yawkey elevated manager Pinky Higgins to the clubs vacant GM post and personally appointed Pesky as Higgins replacement. Inheriting a second-division club, Pesky lasted just two years, but remained associated with the Red Sox for decades in other capacities.

“He was a players manager, said Radatz. It was hard not to like to play for him. My best years were with Johnny Pesky. In 62, when I was Rookie Relief Pitcher of the Year, it was directly attributable to what Johnny had taught me the year before in Seattle.

On Peskys 87th birthday, Sept. 27, 2006, the Red Sox honored him by “officially” naming Fenway Park’s right-field foul pole “Pesky’s Pole.” Mel Parnell, a former teammate, unofficially named the pole for Pesky in 1948 after Pesky wrapped a home run around it.

After the Red Sox appointed Parnell as Pesky’s replacement, Pesky summoned the baseball writers and bid them farewell, saying, “I loved my time in Seattle.”

To which Zimmerman responded, His feet were in Sicks Stadium but his heart was always in Fenway Park.”

———————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com