By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

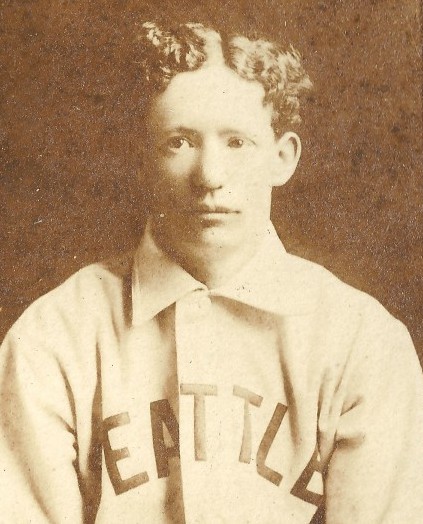

Based on a blurb that appeared in the Feb. 28, 1908 evening edition of The Seattle Times, its baseball reporter, who went unidentified (no bylines in that era), found intriguing the prospect of Dan Dugdales Siwashes coming to terms with 26-year-old shortstop Frank Tealey Raymond.

Dugdale is now dickering for Raymond, the homely youngster who played part of a year with Los Angeles and led the league a mile on his batting average, The Times reporter stated. Tealey is now with Peoria and has developed into a crack fielder.

Raymond did play for Peoria (Distillers) at the time of The Times report and, by all accounts, indeed had a reputation as a crack fielder. However, Raymonds partial season with the Los Angeles Angels (1903) resulted in a .224 batting average (62 games), according to baseball- reference.com, or .219 (37 games), according to mlb.com, hardly a mark that led the league a mile, as the Times man put it.

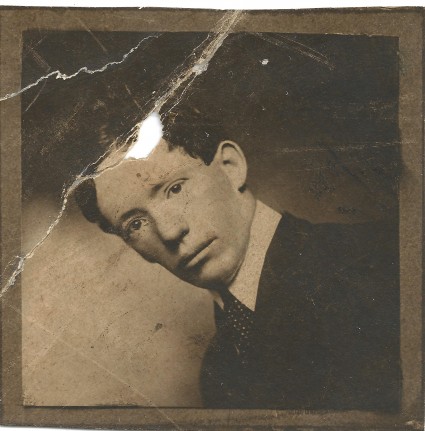

As for The Times unnecessary assessment of Raymond’s looks, the newspaper used that jab frequently in connection with Raymond, at least until he helped lead Dugdales team to a championship. From then on, The Times went out of its way to describe Raymond in more flattering terms.

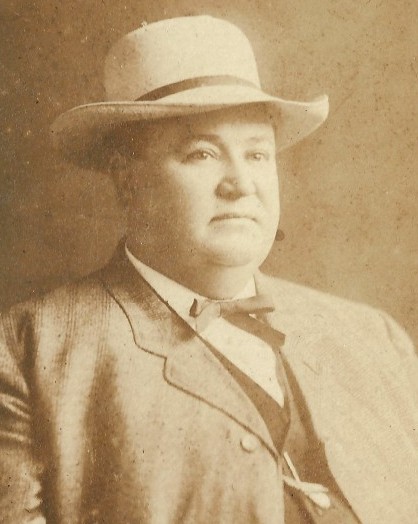

Dugdale spent weeks in advance of the 1908 season attempting to secure Raymond, but couldnt get a deal done, unable to come to financial terms with Peorias owners.

A year later, Dugdale tried again, as The Times explained in a March 14, 1909 story: Dugdale is still trying to land Tealey Raymond, who played such good shortstop for Peoria last year that all the fans there were talking about him. Raymond will not report to Peoria this year for the salary offered him, and he said if Dugdale is not successful in getting him away from that town, he will jump to the California Outlaws.

Newspapers of the day frequently referred to the San Francisco Orphans, a member of the eight-team, Class B California League, as “Outlaws,” and conjured equally colorful nicknames for the league’s other entries, the Alameda Encinals, Fresno Tigers, Oakland Commuters, Sacramento Senators, San Jose Prune Pickers, Santa Cruz Sand Crabs and Stockton Millers.

Raymond is in San Francisco now and says he will sign with the Outlaws next Thursday unless Dugdale gets him, The Times added.

Dugdale got him, although it cost Seattles first baseball mogul more than he planned.

Dugdale could have got Raymond last fall for $300, The Sporting News reported, but Dugdale was rather hoping that Terry McKune would get in shape this winter to play good ball, in which case he would not need Raymond (McKune failed to get into shape). Now Raymonds release cost Dugdale $500.

Thus began in earnest (Tealey played briefly for Spokane and Everett teams in 1905) one of the more remarkable baseball careers in state history, one that would last more than 30 years and take Raymond through Seattle, Tacoma, Yakima and Bellingham as a player, manager, scout, umpire, club director and owner. By the time of Tealeys death everybody called him Tealey — April 3, 1940, he had been associated with four pennant winners, three as a manager, and tutored dozens of players into major league careers.

Born April 12, 1882, in San Franciscos Mission District, Tealey started his baseball career as an enthusiastic sandlotter and broke into pro ball as a 21-year-old in 1903 with the Oakland Reliance of the California State League.

By the time Dugdale purchased Tealey in 1909, Raymond had presaged modern traveling marvel Harry Suitcase Simpson, playing for nearly a dozen teams, some multiple times, including Oakland, Los Angeles (PCL) and San Francisco (PCL) in 1903, San Jose and Stockton (CASL) in 1904, Presidio (CASL) and Everett (Northwestern League) in 1905, Peoria (Three-I League: Indiana, Illinois, Iowa) and San Francisco in 1906 and Peoria again in 2007-09. Tealey also had a brief stint with an “outlaw” Spokane team in 1905.

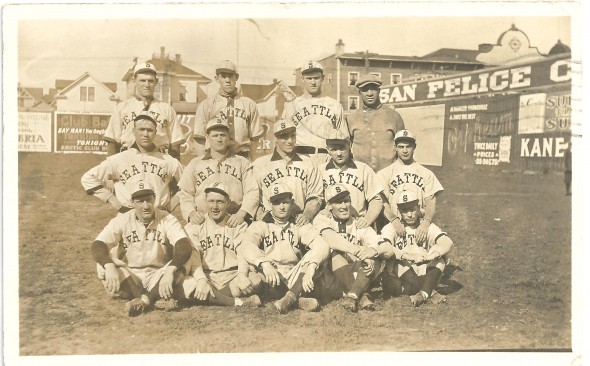

Tealey joined a Dugdale team, led by outfielder/manager Mike Lynch, second baseman Justin Titus Pug Bennett and pitcher Gus Thompson, that The Sporting News picked to win the Northwestern League pennant in a runaway.

The season opened (April 17) with the proper éclat, when Seattle Mayor John F. Miller tried to heave the first (ceremonial) ball over the plate and delivered a wild pitch, The Times reported.

An enterprising Seattle citizen fell off a telegraph pole just outside the grounds, and he doesnt know yet what the score of the opening game was. He had roosted on that pole a long time, thinking to get a view of the game free of charge, but he lost his hold and hit the ground an awful jolt.

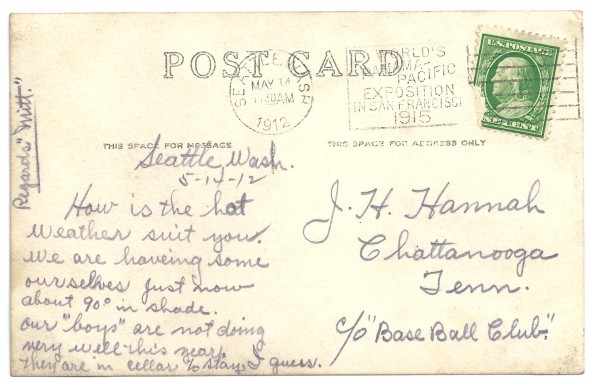

Batting second, Raymond delivered a hit and a stolen base in a 5-2 win over Portland.

Raymond didnt hit much (.203), but started all 167 games at shortstop. On the five occasions that Lynch removed himself from a contest, Lynch placed Raymond in charge of the club (customary for the manager to play), which easily won the pennant by winning 109 games to Spokanes 100.

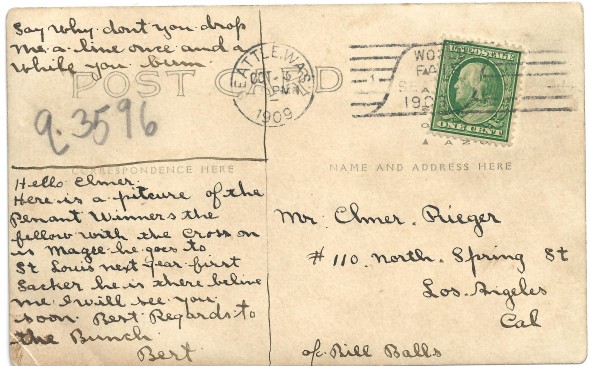

Seattles 1909 Northwestern League champions, the citys first pennant winners since an 1898 Seattle team took the Pacific Northwest League title, featured the leagues top two hitters in Bennett (.314) and Emil Frisk (.307), and a pair of 20-game winners, Thompson (26-8) and Frank Allen (20-6). It also included an infielder named Lee Magee, who hit .264 in 150 games and would become notorious a decade later when, playing for the Cincinnati Reds, he conspired with Hal Chase to throw a game.

Magee ultimately confessed his role in the plot and got tossed out of baseball. Magee sued and the case went to court in 1920. During his testimony, Magee outed Chase, suspected of throwing more than one game during his career. A grand jury investigated Chase and uncovered enough information on baseball betting in general that it began to probe allegations of fixes in the 1919 World Series. If Magee had kept his mouth shut and accepted his ban, there might not have been a Black Sox Scandal. But all of that was a long way off in 1909.

It was a great day for owner Dan Dugdale, whose club won 109 games and lost 58, as Dugdale had been greatly humiliated at the end of the 1908 season when his team finished in last place, Wee Coyle, a former quarterback under Gil Dobie at Washington and later the manager of Seattles Civic Auditorium and Civic Stadium, said in a retrospective the The Times published in 1949. Mayor John F. Miller decorated each player with a gold medal.”

(Dugdales 1909 club is generally referred to today as the Turks, although Seattle newspapers of the time steadfastly avoided using the nickname in connection with the team in any of their game accounts.)

When, in 1910, Bennetts average took a dive to .239, Frisks to .264 and Thompsons record to 8-5, Dugdale’s club plunged into last place. Dugdale got rid of Lynch and managed the club, which had become the Giants, in 1911, guiding it to third place, largely because Art Bues had a career year, batting .352 and hitting 27 of the teams 59 home runs.

After the 1911 season, Dugdale hired Jack Barry as field manager and made another move he thought would lead to a pennant, signing Bill James (see Wayback Machine: Seattle Bill James And the ’12 Giants), a 20-year-old right hander out of a California bush league. But the Giants dropped into last place and stayed there for a month.

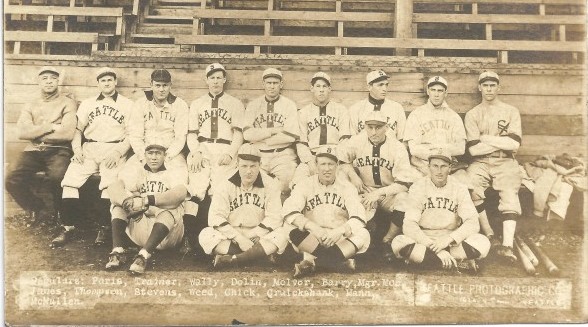

Barry grew weary of James lack of control The Times described James as wild as a March hare — and tried to get Dugdale to release the young pitcher. Instead, after the Giants lost both ends of a doubleheader May 30 at Spokane, Dugdale, who reportedly could not abide either Barrys impatience or impertinence, fired Barry, replacing him with his shortstop, Tealey Raymond.

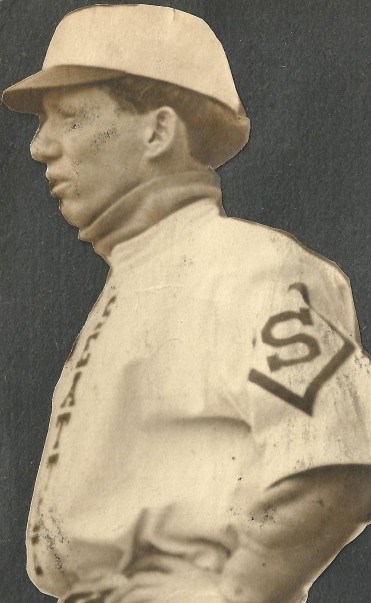

Tealey had bright red hair, stood 5-foot-4 (maybe a tad less) and chatterboxed his way through ball games. When he wasnt on the field, he always seemed to have a cigar going and, according to newspapers of the day, resented every one of the thousands of references to him as a midget manager,” “Tiny Tealey” and “Little Napoleon.”

If the ancient press accounts are accurate, Tealey possessed the acumen of Jack Lelivelt (see Wayback Machine: Jack Lelivelts Seattle Rainiers), who assembled and managed Seattles Pacific Coast League juggernaut from 1938-40, and the passion of Lou Piniella.

Tealey Raymond should be using his noodle in more gainful pursuits than managing a baseball club, opined The Times late in Tealeys Seattle tenure. Anybody who can think as fast as the Little Napoleon thinks ought to be directing the affairs in a billion-dollar corporation.

When Tealey took over the Giants, most of the teams fans despaired that the club could contend for a pennant. But with Tealey running the game, the Giants reeled off 15 consecutive victories to get back into the race.

Tealey took to managing naturally, even developing a reputation as a martinet. Bert Whaling, who caught most of the games for the 1912 Giants, performing well enough to earn a whirl in the major leagues (Boston Braves, 1913-15; in 1913 became the first rookie catcher to win a fielding title), told this story to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer after his own career (1908-26) ended:

They called George Stallings (managed the 1914 Miracle Boston Braves) a slave driver. Yes, and somebody told me Gil Dobie (UW football coach 1908-16) used to crowd five hours of work into a three-hour practice period.

Listen, ever hear of Tealey Raymond? Yes, the little redheaded guy who bossed the Seattle club. Well, Stallings, Dobie, John Napoleon McGraw and all those chaps who made a reputation by making their men work everlastingly were easy compared to Raymond. He is the prize Simon Legree of baseball.

Let me tell you what this guy Raymond did to me. In 1912, Seattle played 150 games and I caught 149 of them. I was working every day nabbing the slants of Big Bill James, Pete Schneider and other Seattle pitchers. Now, if anybody had a kick coming it was me.

I could have hollered about overwork any time and nobody would have blamed me. I never yelped, but just kept plugging away, catching the best ball I knew how and it must have been pretty fair for I went to the big leagues on my showing that year.

One day, the Giants were playing a doubleheader in Spokane and I was behind the plate in the first game, which we won. In the second game, Schneider was heaving em and Pete had lots of stuff but was none too strong on control. So many of Petes benders went wide of the plate that the umpire got to calling all of them balls.

Every once in a while Pete got one over, and one that came sailing across the plate a perfect strike, the ump called ball. I got sore and launched a few blistering remarks and was about to get sent to the showers when Tealey came dashing in.

For the love of Pete, layoff that chatter, yelled Tealey. What are you trying to do, get out of a days work? You only caught six games last week because it rained Friday and now you wanna queer this game by getting the boot so you can lallygag in the shower.

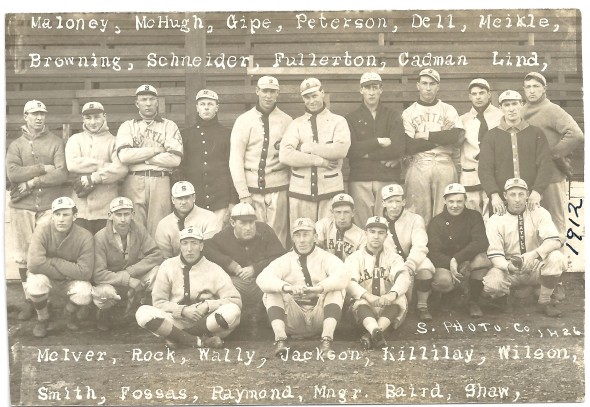

With James winning 26 games, foreshadowing a successful major league career, the Giants finished 99-66, winning the Northwestern League pennant, Tealeys first as a manager, second overall.

His first, in 1909, had been accomplished with a player, Lee Magee, whose testimony helped trigger the Black Sox Scandal. His second, in 1912, was aided for part of the year by Fred McMullin (traded to Tacoma early in the season), who became the “Eighth Man Out” in the same Black Sox Scandal.

Dugdale sold James to the Boston Braves following the 1912 season (two years later, accompanied by the aforementioned Whaling, James went 26-7 for the Miracle Braves), a big reason why the Giants failed to repeat in 1913, when they came in third (89-78). The 1914 Giants moved up a notch, winning 95 to place second.

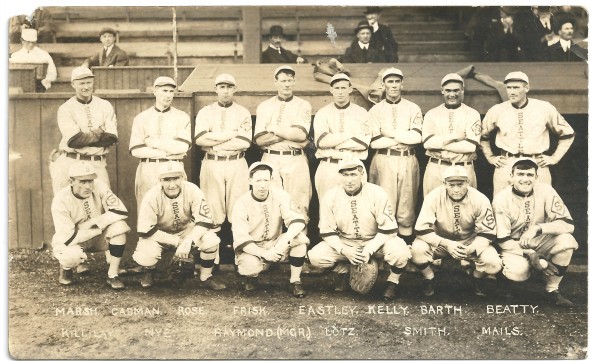

Tealey provided Dugdale another pennant in 1915 with a pitching staff that included Duster Mails (24-18), Al Bonner (20-14) and William Rose (20-10), and hitters Jack Smith (.337), Hunky Shaw (.292) and 40-year-old Emil Frisk (.272), who had been a big part of the 1909 championship team.

Dugdale acquired Mails from the Brooklyn Robyns, who featured a 24-year-old Casey Stengel. Mails had this to say about the source of his nickname Duster: I didnt deliberately try to dust them off. I simply couldnt make the ball go where I wanted it to go. Any batter who faced me did so at his own risk.

With Duster winning 24 games, the Giants beat the Tacoma Tigers by three games for the pennant. But after the Giants dropped to fifth place in 1916, Tealey asked for his release from Dugdale, who granted it Sept. 5, 1916.

Said the Times: Dugdale realizes he is losing a good man when he let Raymond go, but he thinks it is the best thing for Raymond personally and also for the Seattle ball club. A player in the minor leagues seldom stays with one club for eight years, for the fans like to see new faces.

Tealey settled in Tacoma, becoming manager of the Tigers for the 1917 season. Due to World War I, the Northwestern League shut down in mid-July (Tigers had a record of 38-35), casting Tealey out of a managing job.

Tealey spent the balance of 1917 and all of 1918 playing shortstop in the Puget Sound Shipyard League, a collection of semipro teams sponsored by the likes of Seattle Construction & Drydock (Tealeys team), Ames Shipbuilding & Drydock, J.F. Duthie & Company and Sloan Shipyards (Olympia), among others.

Tealey earned a few dollars a game, but made most of his income working full time as a clerk in one of James Brewster’s Seattle cigar stores (Brewster purchased the Giants from Dugdale in 1919), a job he had held during the off-season throughout his eight years with the Giants (Brewster owned a string of cigar shops, today’s equivalent of an internet cafe, which peddled tobacco products, sports tickets and accepted wagers on games, local and national. Tealey reportedly made several financial scores betting on major league baseball, particularly World Series games).

Tealey had an ambition to play at the major league level, but never received an opportunity. His inability to hit had something to do with it, but a long-time friend, quoted in The Bellingham Herald, said there was more to it than that.

“That he didn’t play in the major leagues was not only always a mystery to fans, who marveled at his smoothness afield, but to the smart baseball men of that era,” the unidentified friend told the newspaper. “His lack of size, probably more than anything else, kept him out of the majors. Many writers during the period that Tealey was at his peak as a player, referred to him as the most overlooked player in the game.”

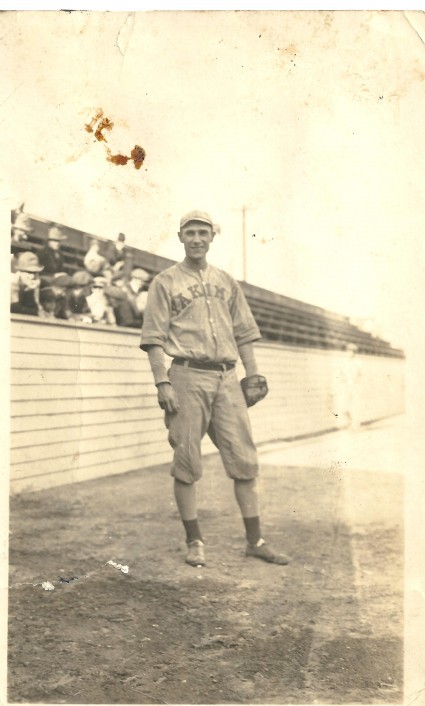

After the war, Tealey moved across the state to manage and play for the Yakima Indians of the Pacific Coast International League. He led the club to a second-place finish in 1920 (minor league legend Paul Strand hit .339 in 103 games) and to the pennant in 1921 (79-36) with a club that featured George “Frenchy” Lafayette, who hit .428, and right hander Guy Cooper, who went 22-7.

After two years in Yakima, Tealey returned to Seattle, sold cigars, worked as a scout for the Seattle Indians, then in their first year in the Pacific Coast League, a job made easier by the fact that Tealey became a roving umpire, and had his pick of games, which provided him the opportunity to scout for talent.

In those days, more than 100 teams played on local diamonds throughout the state: school teams, community teams, business teams, church teams, mill teams, neighborhood teams, semi-pro teams and pro teams.

Tealey mainly worked semipro games, such as the one Aug. 13, 1922, between the Sedro-Woolley Wildmen and the Bloedel Donovan Lumberman, a company team representing Bloedel Donovan Lumber Mills of Clallam County.

One Tealey recommendation: that the Indians sign Victor Pigg, a Bellingham native and player-manager of the Sedro-Woolley Wildmen. Pigg eventually had a five-year career in the Pacific Coast and Western leagues.

Tealey also recommended outfielder and Bellingham native Elmer Bray to the Pacific Coast League after Bray pitched and played first base for Bellingham in 1923-24. Bray had a two-year stay with the Hollywood Stars before returning to Bellingham in 1938.

On July 14, 1922, the semipro Bellingham Elks fired Harold Keene as playing manager (he continued to play) and went after Tealey, who balked initially at taking the job due to the disarray within the Northwest Semipro League (or Community Baseball League, which it was frequently called), of which the Elks were members.

The league threw out a 9-0 Mount Vernon victory over the Knights of Columbus after KOC manager Hunky Shaw, a former Tealey teammate, demonstrated that Mount Vernon used a pitcher who was under contract with the Bloedel Donovan Lumberman, and that Mount Vernon third baseman Red OBrien was not under contract at all, against league rules. Shaw also showed that Mount Vernon tampered with players from many clubs.

Despite the problems within the Northwest Semipro League, Tealey became manager of the Elks in 1923. A year later, he managed the greatest player to come until his control.

Earl Averill started his career in 1920 with the newly formed Snohomish Pilchuckers, a town club named after the nearby Pilchuck River. Averill developed into a player of such promise over the next few years that in early 1924 the citizens of Snohomish took up a collection to send him to the San Bernadino, CA., spring training camp of the Pacific Coast Leagues Seattle Indians, then coming off a 99-win season.

Averill wasnt quite ready for PCL pitching and failed to pass muster with Indians manager Wade “Red” Killefer.

Tealey invited Averill to join the Elks, made a few adjustments to Averills swing (notably, he shortened it) and, according to baseball writer Alex Schults of The Times, before long, Earl was punching hits with regularity.

The San Francisco Seals signed Averill in 1926 and sold him to the Cleveland Indians two years later for $50,000. Between 1929-41, Averill made six American League All-Star teams and batted .318 with a best year of .378 and 232 hits in 1936. He made the Hall of Fame in 1975.

Tealey Raymond should deserve quite a bit of credit for bringing out Earls latent talent, The Times wrote Aug. 13, 1929. He picked up the youngster and after a season under the watchful eye of Tiny Tealey, one of the smartest baseball men in the Northwest, Earl was ready.

The Elks ultimately became the Bellingham Tulips, and Tealey remained associated with the club, either as manager or in an advisory capacity, for the rest of his life. He also served as a director of the Bellingham Chinooks when they were a member of the Western International League in 1938-39.

For many years, Tealey operated a Bellingham cigar store and, between smokes, continued recommending promising semipros to professional teams.

“The little Irishman fused new life into the diamond sport here in the twenties and brought it out of the doldrums,” wrote The Bellingham Herald. “A smart, capable tutor of young players, Tealey provided the incentive that led to baseball careers for many Bellingham players. His judgment of baseball flesh was widely respected among baseball men, and a Raymond recommendation carried an open sesame to professional ball.”

The Thursday, April 4, 1940, edition of The Bellingham Herald carried the following news: “Frank Tealey Raymond has answered the call of the Great Umpire. The diminutive, colorful Irishman, whose friends were legion and who has been an integral part of Bellingham’s baseball life since 1922, passed away at his home at 521 Forest Street at 12:30 o’clock Thursday morning, victim of a heart attack.

“Following the pattern he had imprinted in the countless youngsters he had taken along baseball’s byways, many who went on to stardom in the major leagues, Little Napoleon went down swinging.

“Sufferer of a heart ailment for the past two years (the condition forced Tealey out of baseball in 1938), Tealey worked as usual Wednesday at the tavern he operates with Elmer Bray (one of his former players). He visited his doctor late in the afternoon and went home. At about 6:30 he suffered a heart attack and his condition became worse. After appearing to rally from the administering of a stimulant, he passed away shortly after midnight.”

Tealey left behind wife Emma, two sons, Robert Wagner and Robert Wade Raymond, and three sisters, all of San Francisco. He would have turned 58 had he lived nine more days.

——————————————

Special thanks to researcher/librarian Jeannette Voiland of the Seattle Public Library for retrieving articles, census information and other vital records about Frank Tealey Raymond, and to Faye Fenske of the Bellingham Public Library, for her “archive dive” on behalf of this article.

——————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com