By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

When the University of Washington announced its 11-man All-Century Basketball Team Feb. 13, 2002, the most noticeable thing about the selections was that none played prior to World War II and only three, Jack Nichols (1944, 47-48), Bob Houbregs (1951-53) and Bruno Boin (1956-57, 59), played before 1960.

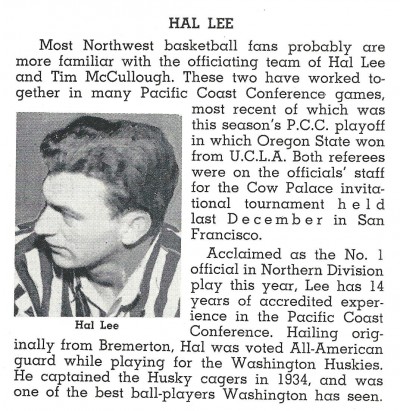

The other curiosity: Seven of the 11 All-Century members failed to earn All-America recognition, but nine players who made All-America prior to WWII were overlooked, including Hal Lee (1932-34) and Bob Galer (1933-35), the first two first-team All-America selections in school history to play together.

Recruited and developed by coach Hec Edmundson (1921-47), Lee and Galer played a very different kind of basketball than post-World War II players. Edmundson had yet to fully develop the fast break offense that would become his hallmark, and the game he taught in the day of Lee and Galer would barely be recognizable today (see Wayback Machine: Ace Coach Hec Edmundson).

Although the Huskies played more of an up-tempo style than most teams (sports writers called them “The Greyhounds”), the jump shot wasn’t used, the center jump ball after each score hadn’t yet been eliminated (that happened in 1937), and stalling was a popular tactic, leading to absurdly low scores by modern standards.

During the Lee-Galer era, Washington defeated Puget Sound 28-6 (Dec. 30, 1931), lost at California 22-21 (March 4, 1932) and defeated Oregon State 24-21 (Feb. 16, 1934). From 1932 through 1934, Washington scored 50 or more points just 14 times in 78 games.

In the most notable games played during the Lee-Galer era, the outcomes of which wound up in a civic parade for the Huskies, Washington, in a three-game playoff for the Pacific Coast Conference championship, lost to USC 27-25 and defeated the Trojans 43-41 and 34-30. Newspapers wrote up those games as “the most exciting in Washington history” (Seattle Times), and declared Lee and Galer “heroes” for the roles they played in them.

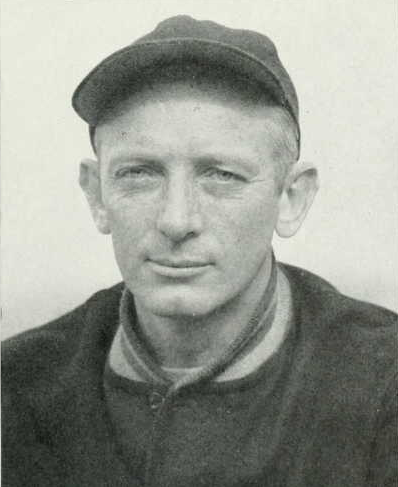

Harold “Hal” Lee, born in Bremerton in 1910, played football, basketball and baseball at Bremerton Union High and, according to the Bremerton Sun, “is generally considered the greatest all-around athlete in pre-World War II Bremerton.”

“He was a totally superior athlete,” long-time Northwest referee Francis “Pop” Hagerty once told The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “His best sports were basketball and baseball, but he was also a heckuva fullback in high school.”

After averaging 16.8 points for Bremerton in 1928, a remarkable average given that teams rarely scored more than 30 in a game in those days, Lee took a year off from school and played for the James Plumbers of the Community Basketball League before enrolling at Washington (his 16.8 average stood as a state record for more than 10 years).

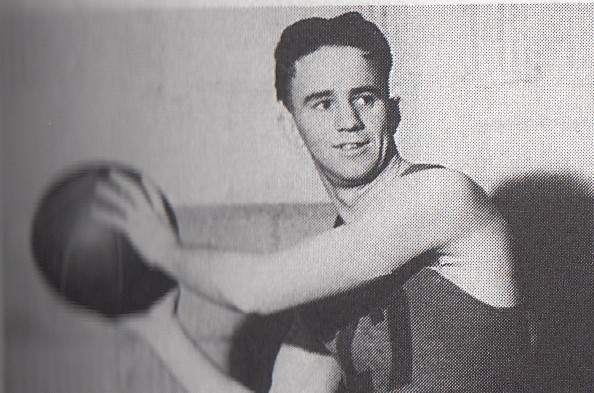

Lee was something of a curiosity, a 6-foot-4, 156-pound point guard on a team that included 6-foot-1 center Clyde Wagner, 5-foot-10 Jack Hanover, 5-foot-11 Joe Weber and the 5-foot-10 Galer, who played forward. Lee was the first “tall” player on the West Coast to play point guard and became a consensus All-America selection. One of the selectors, Literary Digest, employed a 75-member board of national basketball choices to make the picks.

Said Literary Digest: “Hal Lee, Washington captain, is the ranking guard in the Pacific Northwest territory. This tall, rangy fellow can do everything expected of a top-notch basketballer, dribble, pass accurately, handle the ball cleverly and shoot. Lee was a great morale man with the knack of holding his team together. His defensive play was flawless and he possessed an uncanny ability for retrieving rebounds.”

“Lee, primarily, is a ball handler,” Seattle Times sports editor George Varnell wrote after Lee?s All-America selection. “A wonderful dribbler who feeds his forwards effectively, Lee does not rate exceptionally strong in the scoring end, but he is ever dangerous there and as a feeder he is in a class by himself.”

In a 1937 interview, three years after Lee graduated, Washington State’s legendary basketball coach Jack Friel called Lee “The greatest hoopster ever turned out by the Huskies.”

Galer didn’t lag far behind. A more natural scorer than Lee, Galer was born Oct. 24, 1913 in a house at 419 Warren Ave., across the street from the Warren Avenue School. The youngest of three sons of a fire department captain, Galer frequented the Warren Avenue Playfield and by the age of nine was winning awards at the Seattle Times-Park Board Old Woodenface Contest. He attended Queen Anne High and lost no time getting on all-city basketball teams and making a name for himself in football, baseball, tennis and track.

(Once, during a Queen Anne baseball practice, Galer got a base hit and attempted to steal second. The catcher, Johnny Cherberg, who would later become head football coach at the University of Washington, threw to second to nail Galer but instead beaned Galer, knocking him out.)

Galer involved himself in a variety of activities. He joined the YMCA and Boy Scouts, worth mentioning because his scoutmaster was Rusty Callow, then the rowing coach at the University of Washington. Galer also loved to swim in the Lake Washington Canal, near the crew house, and dive off the Montlake Bridge, just to show off (his dare-deviltry would manifest itself later in a more profound way).

Galer played on a UW freshman basketball team that included Harry Givan, who later became one of Northwest’s top amateur golfers and co-founder of Seattle’s Northwest Hospital, and then joined Lee on Edmundson’s varsity.

As a junior in 1933-34, Galer, who got his nickname “Goose” from Lee, scored 176 points, an average of 8.0 per game, to break the conference scoring record, previously held by Oregon State’s Ed Lewis, and in no game did he come up bigger than in a March 10, 1934 contest at USC.

In those days, PCC teams were divided into Northern and Southern divisions, and each year the regular-season winners met in a three-game series to determine the conference championship. Heading into the 1934 PCC playoffs, held at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, no Northern Division team had ever won the playoffs on the home court of the Southern Division champion.

In 1924, Washington, the Northern winner, went to Berkeley and dropped two straight to California. Two years later, Oregon, the Northern winner, lost two straight at Cal. In 1928, Washington dropped two straight at USC, and in 1930 Washington again went to Los Angeles to face USC and actually won the second game of the series, 36-12, the first time a Northern team had won on a Southern court. But USC came back in the third game and defeated UW 35-29. The series of 1932 saw Washington travel to Berkeley. Cal won both.

On March 9, 1934, to open the PCC playoffs, USC defeated Washington 27-25 after, as The Times described it, “staving off one of the most riotous closing rushes ever seen.” Washington came from far behind in the second half and forced USC to resort to keep-away tactics in the final minute to put an end to the Husky drive.

Washington, which played without injured center Clyde Wagner, fell behind 27-16, but Weber sank a long set shot and Galer hit two free throws. When Lee converted a three-point play, Washington pulled to within 27-25, which is how it ended. Lee scored seven points to lead the Huskies.

One night later, UW staged a great overtime comeback in front of 6,000 to beat USC 43-41 in the second game of the series. Galer had a season-high 16 points and Lee six.

UW and USC took a day off and played again March 12. For the third straight game, USC had a halftime lead (16-9), but Lee and Galer roused the Huskies in the second half to a 34-30 victory. Three days later, upon its return to Seattle, Edmundson’s team was given, as The Times wrote, “The greatest homecoming celebration ever accorded a varsity athletic team.” It included a parade from Tacoma to Seattle and a banquet at the Washington Athletic Pavilion at which Lee received the first Edmundson Inspirational Award.

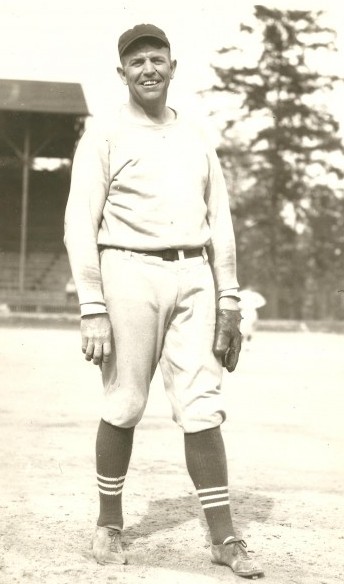

Lee, who played for Tubby Graves’ UW baseball team for three years as a first baseman/outfielder (batted .400 as a senior) graduated four months after the USC series and became something of an athletic vagabond, first joining Gilmore Oil of the Northwest Community Basketball League, an eight-team operation that also included the Italian Athletic Club, Ballard, Seattle De Molay, Bellingham-Bostrom’s, Everett Shadoff’s, Kelly Printing and Mt. Vernon-Parker’s.

Later that year (1935), Lee played baseball for the Bellingham Models of the Northwest League, and the following winter suited up for the Wheeler-Osgood AAU basketball team that also featured former Huskies Ralph Bishop and Doug McClary and played Washington in the first two games of the 1936-37 season.

Between 1937-43, Lee played baseball for the Renton Athletic Club (teammate of future Rainiers icon Edo Vanni), Wenatchee Chiefs of the Western International League and Dallas of the Texas League, and basketball for the Tacoma Shipyards team. After joining the Army in the spring of 1943, Lee played basketball and baseball for the Fort Lewis Warriors.

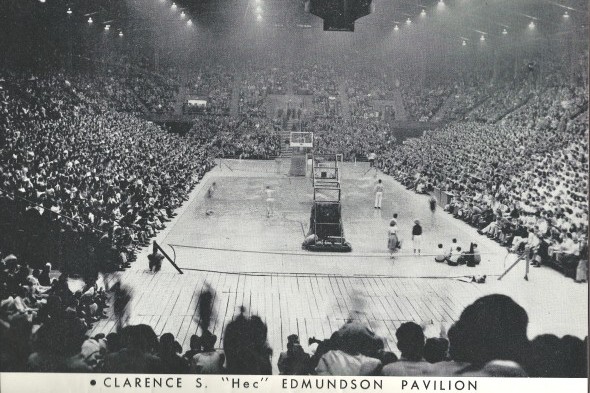

After World War II, Lee became a full-time basketball referee in the Pacific Coast Conference’s Northern Division. Lee and future University of Washington basketball coach Art McLarney (1948-50) teamed up to officiate numerous UW games, including a pair of Harlem Globetrotter exhibitions at the Washington Athletic Pavilion. Lee’s best officiating assignment: the 1949 NCAA Final Four, held on the UW campus.

By that time, Bobby Galer had become famous for reasons having nothing to do with sports, but he left quite an athletic legacy at Washington. He made the Helms Foundation All-America basketball team in 1934 and 1935, earned the second Edmundson Inspirational Award a year after Lee won the first, won letters in track and field and graduated with a degree in commercial engineering. Galer financed his education by pulling night duty in the UW bookstore.

Since Galer’s personal hero was Charles Lindberg, he decided to become a fly boy, joined the Marine Corps and went to Pensacola, FL., as an aviation cadet. Galer was there only a short time when he received a presidential commission as a second lieutenant.

Galer began his military service in the Virgin Islands, where he stayed two years and served as the base recreation officer (he won the men’s singles tennis championship of St. Thomas in 1937). After the Virgin Islands, Galer spent three months in Quantico, VA., six months in San Diego and then left for Honolulu.

In 1940, Galer had his first brush with disaster when he was forced to ditch a biplane in the Pacific while making an approach to the carrier USS Saratoga.

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, Galer, who had spent the previous night at a friend’s house in the mountains overlooking Pearl Harbor, rose early to get in a round of golf.

“We had just come out with the first Bloody Marys of the day in our hands,” Galer told military historian Col. Joseph Alexander. “That?s when we saw that the Japanese attack was underway.”

Galer and his golfing buddy found an empty swimming pool, jumped into it for cover, and began firing rifles at Japanese war planes as they flew overhead.

Promoted to major in early 1942, Galer spent most of that year training new fighter pilots, and late that summer deployed to the British Solomon Islands as commander of Marine Fighter Squadron 224. Military historian Alexander described what happened next:

“The green pilots of 224 got their first trial by fire on Sept. 2. Galer, as unproven in combat as any of his pilots, provided an inspirational example, coolly entering a swirling melee to down a Zero and a Mitsubishi Type 97 bomber. Three days later he downed another Zero.

“On Sept. 11, he recorded kills number four and five, thus qualifying officially as an ace. The distinction came at a price. A Zero appeared on his tail and shot him down. Galer bailed out of his burning Wildcat, landing in Iron Bottom Sound only a few miles off Lunga Point. Repeatedly, Galer would be shot down in aerial combat, only to show up at Henderson Field, soaking wet, but ready to fly the next mission.”

When word of Galer’s heroics reached Seattle, The Times published a lengthy article on the former UW basketball star shooting down one Japanese plane after another. The Times article quoted Edmundson as saying, “I don?t know where he got the bug, but he was sure crazy to fly. The only time I ever saw him get ruffled or upset was when he got his teeth banged in a game. He wanted to know if it would hurt his chance of passing the military physical. But that kid’s got a wonderful eye. He’s a terrific fighter, he’s full of confidence and determination, and he’s got ice water in his veins. I’d sure hate to have him on my tail.”

On 28 Sept., Marine Coastwatchers spotted a large concentration of Japanese aircraft headed for Guadalcanal. Galer led the attack, shooting down three bombers in less than a minute. Two weeks later, Japanese fighter pilots shot down Galer, raking his Wildcat “from wingtip to wingtip, through cockpit and engine, which quit.” Galer ditched in the waters east-northeast of Guadalcanal, swam for an hour to reach Mandoliana Island and collapsed in exhaustion on the beach.

Friendly Solomon Islanders discovered him and delivered him by outrigger canoe to the Marine outpost on Tulagi. Galer returned to Guadalcanal the next day to surprise his squadron members as they mournfully prepared a memorial in his honor.

Galer continued to lead his pilots in their daily battles over Henderson Field. He ultimately shot down 13 enemy planes.

The following March (1943), Galer received the Medal of Honor, presented at the White House by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Galer’s citation said:

“The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Major Robert Edward Galer, United States Marine Corps, for conspicuous heroism and courage above and beyond the call of duty as leader of Marine Fighting Squadron 224 in aerial combat with enemy Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands area during the month of October 1942.

“Leading his squadron repeatedly in daring and aggressive raids against Japanese aerial forces, vastly superior in numbers, Major Galer availed himself of every favorable attack opportunity, individually shooting down 11 enemy bomber and fighter aircraft over a period of 29 days.

“Though suffering the extreme physical strain attendant upon protracted fighter operations at an altitude above 25,000 feet, the squadron under his zealous and inspiring leadership shot down a total of 27 Japanese planes. His superb airmanship, his outstanding skill and personal valor reflect great credit upon Major Galer’s gallant fighting spirit and upon the U.S. Naval Service.”

After earning the Medal of Honor, Galer commanded a Marine Air Wing in Korea and on one occasion was shot down in enemy territory. In a 12-year span, Galer crashed or bailed out of five stricken planes, including four times due to enemy fire. Galer always shrugged off the incidents as “the cost of doing business.”

“Galer survived the war with a professional reputation as a gifted pilot and a sensible leader,” Col. Alexander wrote. “The fact that Galer, a fighter pilot, spent so much time in foxholes and slit trenches endeared him to the infantry as well.”

Galer flew his final mission Aug. 5, 1951 when he led 31 planes against a tungsten mine near Ogu-long, Korea. Galer’s plane was shot down, he bailed out and crash landed, suffering a separated shoulder and cracked ribs.

Galer retired as a brigadier general in 1957 with two Distinguished Flying Crosses and a Legion of Merit in addition to his Medal of Honor. He went to work for Ling-Temco-Vought in Dallas as general manager of the aeronautics and missile division. Later he qualified as a professional engineer in the state of Texas and became licensed as a real-estate broker and appraiser. As late as age 89, he still went to work every day.

Bobby Galer died in Dallas June 27, 2007 of a stroke at age 91, 16 years after he entered the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame and 14 after he was inducted into the Husky Hall of Fame.

Lee, who died Oct. 16, 1977 at age 67 in his hometown of Bremerton, preceded Galer into the state hall by five years (1974) and into the Husky hall by two (1987). Although he didn’t make Washington’s All-Centennial Basketball team, Lee made its All-Centennial Baseball team, announced in 2001.

————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David?s ? Wayback Machine Archive.? David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

1 Comment

I used to hear a lot about those Husky teams from my grandparents…Joe Weber’s brother married Jack Hanover’s sister. They were both tremendous multi-sport athletes.