Peller Phillips died in Seattle on Feb. 18 from congestive heart failure. He was 72. He lived a full life. Yet there was a time when Phillips feared the end for him might come as a young man when he wasn’t looking, in a sinister and brutal manner, at the hands of some shadowy Mafia figure.

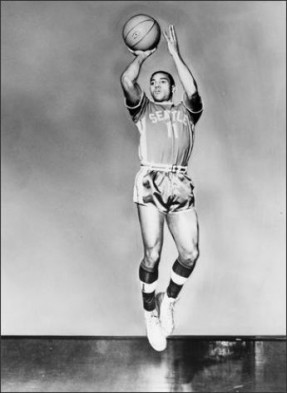

Phillips forever will be known as the centerpiece of one of the city’s worst and most theatrical sports scandals: A Seattle University basketball player who stood accused — and was quietly exonerated — of point-shaving in an obscure game at the behest of the Chicago underworld.

“It was four or five years before I felt better and thought there wouldn’t be any retaliation,” the former point guard said in 2009. “Even today, who knows with the lifestyles those guys lead; you don’t know who’s still alive. I really feared for my life. I’m still real cautious about the whole thing.”

Phillips became a restaurant owner, mortgage broker, teacher, coach and proud father of four, including three college scholarship track athletes. He was a solid Seattle citizen. However, he could never quite shake a moment of youthful vulnerability when he let a former junior-college basketball teammate back into his life and paid for it dearly.

On Feb. 18, 1965, on the same day that later marked his death, the arrests of Phillips and teammate Charlie Williams by the FBI were splashed across the front pages of the Seattle newspapers in bold headlines and large photos. They were formally charged with bribery conspiracy.

These two starting guards and a third teammate, reserve center L.J. Wheeler, were expelled from school for failure to report a bribe, ending their careers with three games left on the schedule and preventing a 19-7 Seattle University team from qualifying for the NCAA Tournament.

“I really felt bad for the school, the coaches, the fans,” Phillips said. “It took me years to get over it. It’s maybe something you never get over.”

After conducting interviews and reviewing game film of the targeted game — an 89-72 victory over Idaho at the then-Seattle Center Coliseum — the feds promptly withdrew their conspiracy charges. They discovered that Phillips, a noted ball-handling wizard, and Williams, the team’s leading scorer at 20.6 points per game, barely played in the second half of the blowout, hence their inability to affect the point spread.

Two Chicago men, Leo Casale and Joseph Polito, were convicted later that summer for their roles in the proposed SU point-fixing scheme. Casale was Phillips’ former JC teammate who served time in several prisons. In 1967, Polito was fatally gunned down in Chicago, his murder coming after he twice had turned government witness in the case, heightening tensions in Seattle.

Casale, contacted in 2009, loosely admitted that he had Chicago underworld ties. “I tried to get out of it, but what took me out of it got me right back into it,” said Casale, who managed a place called the Action A-Go-Go Lounge. “You don’t operate a nightclub in Chicago without mob influence, plus the fact I’m Italian. I know every wise guy in town. I’m connected in a sense. Do I do what they do? No.”

It was a set-up all along and Phillips was singled out as an unwitting pawn. At least that’s what the FBI told him. The smarmy hoop stuff unfolded like this:

A Detroit native, Phillips played two years for then-Coalinga Junior College outside of Fresno, CA. It was there he teamed briefly with the fast-talking, 5-foot-7 Casale, who had lost his spot on the team because of grades. They played 1-on-1 regularly. Phillips sneaked sandwiches to him from the school cafeteria. And then Casale was gone.

Two years later, Phillips and SU were in Chicago to face DePaul shortly before Christmas when Casale contacted his old teammate. They were in his hometown and he wanted to reconnect. Casale casually mentioned that he was going to bet on the upcoming game. Phillips thought he was referring to nothing more than a friendly wager with a buddy. He was oh so wrong about that.

Following the Chieftains’ 91-77 loss, Casale invited Phillips and other SU players to visit the south Chicago restaurant that he managed. Casale told them how his friends had lost a lot of money on the game and wanted a chance to recoup their losses. The street-wise Wheeler, a noted pool shark and gambler himself and originally from Baltimore, brashly suggested that Casale call them from time to time for game insights if he wanted to continue betting on SU.

“I thought I’d never hear from him,” Phillips said.

Casale called him at his Seattle apartment a month later. Phillips was stunned. Casale asked for insider information on the Idaho game. Phillips felt uncomfortable with the conversation and said as much. It got worse. Casale showed up on a road trip, in the lobby of a Spokane hotel, before the Chieftains played their rematch with Idaho, a 97-76 loss.

Representing four Mafia families, according to the FBI, Casale asked specifically if Phillips or any of the other players would influence the point spread. Reports suggested that Williams was offered $2,000 for his involvement. Casale was summarily rejected by everyone on the team.

Before he left, Casale handed $130 to Phillips supposedly for inconveniencing him. Phillips rejected the cash, before giving in and accepting it under pressure from a teammate. Wheeler wanted a cut, and got $50.

“The FBI told us that that this was a common practice, and it had happened at several schools,” Phillips said. “[The agent] said the money wasn’t a gift. He said you could call it dirty money, used to make sure we didn’t say anything.”

In Spokane, Casale tried everything he could to close a point-shaving deal. He said there were threats made on his life. He also said Phillips was in danger.

“He said we needed to cooperate with him,” Phillips recounted. “There were people who were very dangerous, who might harm him and harm me. I felt intimidated by the situation.”

Besides accepting the money, Phillips and the others made another fateful mistake: They didn’t tell anyone else of the bribe offer. They tried to do damage control. They were judged guilty by their silence, on many basketball fronts.

“I had a conversation with Charlie and I talked to him about going to the coach,” Phillips said, referring to Bob Boyd. “I remember Charlie saying, ‘If we go to the coach, things might get pretty ugly. It might be best to not say anything.’ ”

The son of a Tacoma minister, Williams was banned from the NBA because of his school expulsion, even with the expansion Seattle SuperSonics eager to sign him and trying hard to overturn his renegade status. Williams moved to the ABA and helped lead the Pittsburgh Pipers to the 1968 league title, scoring 35 points in the deciding game. When his pro career ended, he became a steel company sales representative in Cleveland, where he has resisted all requests to talk about the SU scandal. He and Phillips never really hashed it out either.

“Charlie was more or less an innocent victim of the whole thing, and I felt worse about Charlie’s situation than anything,” Phillips said. “It’s part of his past and he doesn’t want to talk about. He went on and had success. He moved to a different city and settled down.”

Wheeler, who was nicknamed “the Rock,” turned to heavyweight boxing when he wasn’t hanging out in pool parlors. He was killed in some sort of altercation in St. Louis.

Phillips felt so shamed by the point-shaving accusations and school ouster that he didn’t play or watch basketball for four years. In 1969, however, the Harlem Globetrotters offered him $10,000 to join their traveling squad. Team representatives met him in the then-Olympic Hotel, laying out a new uniform for him to see. Walt Hazzard, a college opponent and a friend now with the Sonics, encouraged him to join the Trotters or follow Williams to the ABA.

Phillips decided the toll on his family was too great to become a basketball vagabond and he declined. He resumed classes at Seattle U and obtained a degree. He reconnected with former athletic director Eddie O’Brien and other school officials, and soon he was receiving and accepting invitations to join athletics-related dinners.

In 2009, Phillips figured enough time had passed and he agreed to tell his story to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer shortly before the newspaper ceased operation. HBO’s “Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel” later inquired about doing its own version. Phillips was amazed at all the positive reaction he received. His junior college, renamed West Hills College Coalinga, even sought him out upon seeing the P-I article and elected him to the school’s athletic hall of fame in 2010, helping restore his basketball image some.

Phillips chose not to dwell on his embarrassing past, even with those closest to him, always a little fearful about that deep-rooted Mafia connection. As it turned out, he was the victim only of intimidation tactics.

“I went to jail and took the heat off all those creeps,” Casale said. “All of the problems as a result of that incident stayed in Chicago. Peller was never in jeopardy. I was never going to let that happen.”

2 Comments

…wow….

I remember Peller Phillips coaching youth basketball in the later ’60’s at the Jewish Community Center. He was a caring, patient man who should have been treated better.