By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

In the sporting era that preceded free agency and multi-million-dollar contracts, professional athletes commonly supplemented their sports salaries by taking offseason odd jobs — or odd, offseason jobs. In Paul Gregory’s time with the Seattle Indians and Rainiers (1936-41), his teammates, as well as most other Seattle athletes, found work in a variety of ways.

Star pitcher Kewpie Dick Barrett of the Rainiers peddled insurance policies, among other things. Outfielder Bill Lawrence toiled as a security guard at the Santa Anita and Hollywood Park race tracks. Coffee Joe Coscarart worked in a downtown Seattle florist shop, and catcher Gilly Campbell labored in Emil Sick’s Rainier Brewery.

Early in his career, slugger Mike Hunt wielded a pick and shovel for the El Centro, CA., street department. Later in his career, he performed clerical chores for the Washington State Patrol (see Wayback Machine: Mike Hunt, ‘Old Baggy Pants’).

During Gregory’s career, which overlapped the Seattle Indians and Seattle Rainiers, a sports fan could stroll into a downtown department store and purchase men’s furnishings from popular third baseman Dick Gyselman, or fill his car with gas at a station owned and operated by middleweight boxing champion Al Hostak and his two brothers.

Hal Tabor, a speedy forward for the Seattle Sea Hawks hockey team from 1933-41, also worked in a gas station across town from Hostak’s.

Tabor’s teammate, John Houbregs (father of Bob) spent his days in a Seattle brewery. Another Sea Hawk, Frank Jerwa, bartended in Vancouver, B.C., while “Silent” Danny Cox, who’d had a 319-game run in the National Hockey League with the Maple Leafs, Rangers and Senators, drove a beer truck in Port Arthur, Ontario. In Ottawa, offseason Seattle goalkeeper Emmett Venne worked as a tout at the local thoroughbred track.

One of Tabor’s linemates, Ken Doraty, owned and operated a 40-room motel in Morris, Saskatchewan, a town midway between Moose Jaw and Swift Current. Ralph Blythe returned home to Chilliwack, B.C., after every Sea Hawk season and painted houses.

Ranching attracted a number of Seattle’s professional athletes during the time that Gregory’s name frequently appeared in Seattle newspaper headlines. “Farmer” Hal Turpin of the Rainiers ran his spread in Yoncala, OR., and teammate Les Webber, who won 30 games for the Rainiers in 1939-40, worked on his father’s ranch in central California, near Santa Maria.

Gregory never did have an offseason job during the years he pitched for the Rainiers. Instead, like Fred Hutchinson, he took classes at the University of Washington with the specific aim of receiving a Master’s degree in physical education.

During his baseball career, Gregory frequently told Seattle reporters that after he retired he would pursue a PhD at Columbia University.

World War II scotched that plan and also derailed a splendid baseball career that had its roots in Tomnolen, MI., where Paul Edwin Gregory was born June 9, 1908.

He grew to be 6-foot-2 and 180 pounds and starred in three sports (football, basketball and baseball) at Mississippi State University from 1926-30.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in physical education, Gregory signed his first professional contract with the Class A Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association and supplemented his income for two years by coaching high school football.

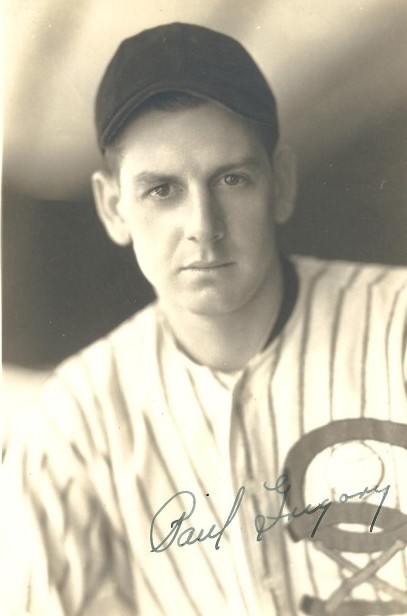

Although Gregory posted only a modest 8-6 record with a 5.17 ERA in his first professional season, he won a job with the 1932 Chicago White Sox and made his major league debut at 23.

Gregory spent most of that season as a reliever but received nine spot starts in 33 games and worked 117 innings, finishing with a 5-3 record. His first win, May 22 at Comiskey Park, was a 3-2 decision over a Detroit Tigers team that included a future Rainiers teammate, Jo Jo White, who went 1-for-3.

Gregory won three of his final four starts, notably outdueling 24-game winner Lefty Gomez in an 8-5 win over the New York Yankees Sept. 15, and beating Detroit 3-1 Sept. 21 (future Hall of Famer Charlie Gehringer of the Tigers went 0-for-4).

Gregory split 1933 between Chicago and AA Milwaukee of the American Association and didn’t have much success in the majors, finishing 4-11. But he had one memorable performance.

On May 26 at Yankee Stadium, playing in a lineup that included Al Simmons, Luke Appling and Jimmy Dykes, Gregory pinned an 0-for-5 on Babe Ruth, an 0-for-4 on Tony Lazzeri, an 0-for-3 on Bill Dickey (all future Hall of Famers) and outdueled Red Ruffing in an 8-6 White Sox victory. Ruth, Lazzeri, Dickey and Ruffing all made the Hall of Fame.

Gregory’s major league career spanned 56 games, including 26 starts, and ended April 2, 1934 when the White Sox sold him to the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League. The Solons, in turn, traded Gregory and RHP Lou Koupal to the Seattle Indians Nov. 14, 1935 for catcher John Bottarini in the first of several deals pulled off by owner Bill Klepper to rebuild his ball club.

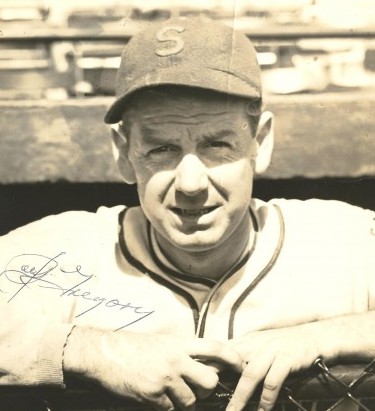

Gregory, who produced an 11-16, 4.27 ERA mark for seventh-place Sacramento, signed his first Rainiers contract Feb. 8 and said, “I’m tickled to death to land in Seattle. The loyal fans there are the talk of the league. I’m sure I can win for (manager) Dutch Ruether (see Wayback Machine: Walter Ruether, ‘The Dutchman’).

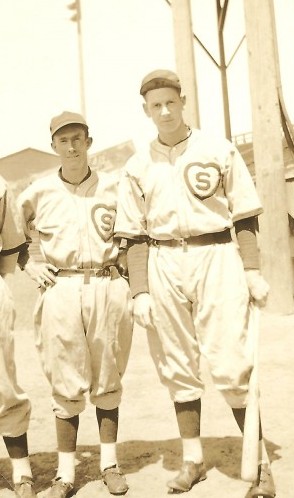

Gregory joined an Indians club coming off a 80-93 season and a sixth-place finish, just a notch ahead of Sacramento. To Koupal’s 23 wins and Barrett’s 22, Gregory added 15 and a 3.88 ERA, making Klepper, a year away from selling his ball club to Emil Sick, seem a genius.

Koupal and Gregory combined for 38 wins while the catcher for whom they had been traded, Bottarini, was sold by Sacramento to Los Angeles for $3,000 without ever having played for the Solons.

Gregory never became the ace of Seattle’s staff, most often serving as the No. 3 or No. 4 starter in the rotation. But in the six years he pitched for the Indians/Rainiers, he won 97 games and lost 79, including 41 victories and 35 losses in Seattle’s pennant-winning seasons of 1939-41 (in Jamie Moyer’s best six years with the Mariners – 1999-04 – he won 88 games).

Barrett won 126 and lost 80 during Gregory’s Seattle stay – 29 more victories but also one more loss. Turpin, who joined the club in 1937, went 92-52 in those six seasons (see Wayback Machines ‘Kewpie Dick & The Rainiers’ and ‘Farmer Hal Turpin’).

After going 15-14 in an injury-plagued first season (1936), Gregory became a 20-game winner for the first time in 1937, when his 20-15 record, 3.88 ERA and .571 winning percentage led the staff (Barrett finished 20-18, 3.89, .526). But 1937 was a difficult year for the Indians, who finished 81-96 under Spencer Abbott and Johnny Bassler.

Klepper fired Bassler following the final pitch of the season after Bassler deliberately disobeyed a Klepper order prior to the second game of a season-ending doubleheader.

Barrett had won his 19th game in the opener, and Klepper didn’t want to risk having to pay Barrett a $250 bonus for winning 20 games. But Bassler used Barrett anyway and he won his 20th, a victory that cost Bassler his job.

Klepper’s financial problems were legendary. Before Barrett’s doubleheader victory, a dozen federal agents swooped through the Civic Field gates, followed by a phalanx of Washington cops representing the state tax commission, all demanding that the fifth-place and cash-strapped Indians hand over all outstanding admission taxes in what amounted to a blatant money grab.

The next morning, the Seattle Post-Intelligence’s main headline blared, “G-Men Seize Ball Game Cash.”

Prior to that banner-headline raid, Rainiers players staged a sit-down strike when Klepper couldn’t come up with the money to pay them.

“He (Klepper) got behind on salaries and we pulled a sit-down strike,” Gregory told The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “It was a sunny day, I remember. We had a full crowd. They were giving away an automobile. We took our infield workout, then put on our street clothes and sat down.

“Klepper came running down, wondering what was the matter. We told him we had to be paid or we wouldn’t play. So he came down with several sacks of coins and paid us off.”

A beleaguered Klepper sold the Indians following the 1937 season to Emil Sick, who renamed them the Rainiers and built them a new ballpark, Sicks’ Stadium, in which Gregory continued to flourish. In 1938, when 19-year-old Fred Hutchinson went 25-7 2.48 ERA for the Rainiers, Gregory went 21-15.

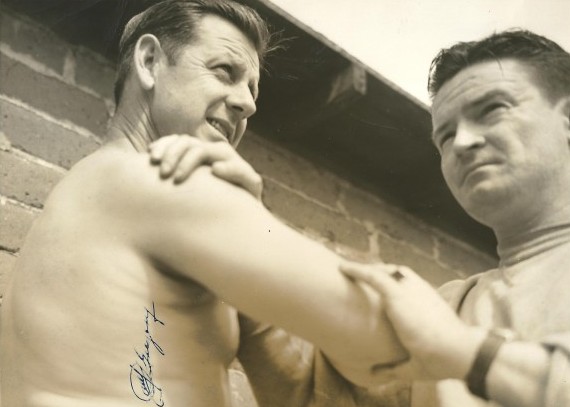

For the 1939 Pacific Coast League champions, Gregory posted an 18-11 mark and probably would have exceeded 20 wins had he not missed several weeks during the middle of the season when some buckshot lodged in his right hand (it had been there since a childhood hunting accident) caused swelling and kept him from gripping the ball properly (Dr. W.A. Glasgow removed the buckshot after the season).

Like Moyer more than a half a century later, Gregory didn’t strike out a lot of batters, getting most of his outs on ground balls, and never had the kind of “wow” performance that dropped jaws. He came closest July 22, 1939, when he won his 15thgame by beating Oakland 5-4 with a walk-off RBI in the bottom of the ninth inning.

Gregory’s first start with the Indians, April 15, 1936, was fairly representative of his Seattle career. Aided by a fourth-inning triple play, he defeated the San Francisco Seals 4-2 by allowing six hits with three strikeouts and two walks. Beyond that, Gregory threw a lot of three-to-six hitters and recorded dozens of 5-3, 4-2 and 3-1 wins.

Gregory was proficient enough over his six Seattle seasons to draw periodic interest from other clubs.

In December 1938, the St. Louis Browns, who had just acquired catcher Hal Spindel from the Rainiers, made a play for Gregory at baseball’s winter meetings in New York. Seattle manager Jack Lelivelt told Seattle newspapers that he would swap Gregory if the Browns could assemble the right package.

“I know the Browns are interested in Gregory, but don’t know if they can produce the players who will satisfy Lelivelt,” said B.N. Hutchinson, public relations counsel for the Rainiers.

The Browns couldn’t – or wouldn’t. Another time, the Portland Beavers wanted Gregory, but offered Whitey Hilcher, a right-handed pitcher who attended the University of Alabama. Lelivelt wouldn’t bite.

Gregory began taking graduate courses at the University of Washington following the 1939 season, and over the winter worked out with Tubby Graves’ Husky baseball team.

By 1942, he received his Master’s degree in physical education and considered walking away from baseball in order to begin his career as a coach and teacher.

Gregory signed to pitch for the Rainiers in 1942 and reported to spring training in San Fernando, CA. But after spending two weeks in camp, the Navy beckoned, ordering him to report to Annapolis, MD., for a month of training in the Navy’s physical education program.

Once certified as an athletic instructor in the Air Corps, Gregory was sent to the Naval Training Base in Moraga, CA., where he was named coach of the base’s baseball team.

Discharged from the Navy in 1946, Gregory returned to Seattle and attempted to revive his baseball career, but the four-year absence from the game had taken too much of a toll.

On April 26, the Rainiers traded Gregory to the Hollywood Stars for infielder Bob Kahle. Over the 1946 season he went 9-5. After going 0-7 in 1947, Gregory retired with 145 minor league victories, including 17 shutouts.

Late in 1947, Mississippi State baseball coach Drudy Noble, also the school’s athletic director, asked Gregory to become head coach of the MSU varsity basketball team. Gregory stayed in charge from 1947 through 1955, then replaced Noble as head baseball coach.

From 1954 through 1974, Gregory led the Bulldogs to 15 winning seasons, claiming four Southeastern Conference titles (1965–66, 1970–71) and a berth to the 1971 College World Series along the way. As a college baseball coach, Gregory had a record of 328-200.

Paul “Pops” Gregory was inducted into the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 1977 and the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and Museumin 1982. He died of heart failure Sept. 16, 1999 in Southaven, MI., at the age of 91.

—————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com