By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Dewey Soriano got his start in baseball growing up in the Rainier Valley in the 1930s. He was a friend of Fred Hutchinson’s, and any friend of Fred’s had to play baseball. Soriano got his start in business as a young teen peddling concessions at Civic Stadium, home of the Seattle Indians, and at University of Washington football games.

“I made my first sale when I was a kid,” Soriano told Georg N. Myers of The Seattle Times in 1960. “I’ll never forget, it was four ice cream bars. But I remember my last sale even better. It was in 1936 when Washington beat Washington State 40-0 to go to the Rose Bowl.

“In the last quarter, a Washington fan started celebrating by throwing handfuls of peanuts all over the place. He told me, ‘You just keep handing me the peanuts and keep count.’ He threw 70 bags of peanuts, $7 worth.”

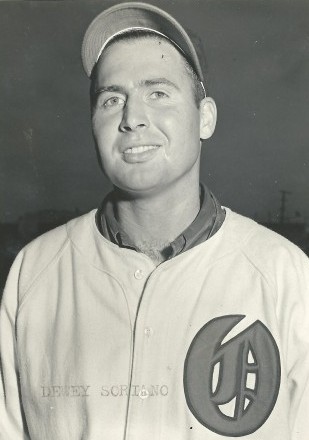

Soriano evolved from an ice cream and peanut vendor to a gifted amateur pitcher/first baseman. Then he reached the minor leagues and might have made it to the majors if World War II hadn’t sabotaged the baseball careers of numerous players.

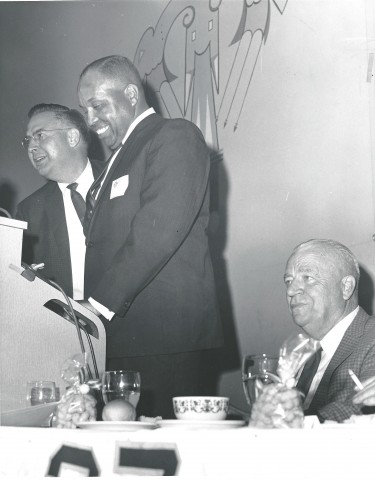

By the time Soriano reached 40, he had been an owner, general manager and league president, perhaps his greatest feat of job juggling occurring from 1950-52 when he not only owned his own team, but served as its president, GM and star pitcher.

Soriano had his pitching hat on one night in 1949 when his team, the Yakima Bears of the Class B Western International League, hosted the Vancouver Capilanos, managed by Bill Brenner, who would also manage the Seattle Rainiers for part of the 1956 season.

“Bud Sheely, who later caught for the Rainiers, hit me for a homer with the bases loaded,” Soriano explained. “Vancouver got in about seven runs that inning. Our manager was Joe Orengo. He came out to have a talk with the president, general manager and pitcher.

“He said, ‘Dewey, what happened?’

“I said, ‘Joe, the gamblers got to me.’

“He said, “Gimme that ball!’

“At least when I lost,” quipped Soriano, “I did it right.”

Soriano made headlines throughout his three decades in professional baseball, none bolder than in the late 1960s when, with brother Max, he brought major league baseball to Seattle for the first time.

For both Sorianos, the experience proved wrenching when it should have been the most exhilarating time in their lengthy baseball careers.

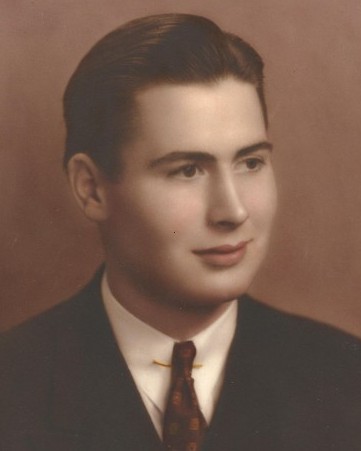

Born Feb. 8, 1920, in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, to Angel Lorenzo Soriano, a poor fisherman from Torrevieja in Spain’s Alicante province who operated halibut boats in the Georgia Straits on up to Alaska, and Anna Bundgaard, a farmer’s daughter from Denmark, Dewey Soriano was one of 10 little Sorianos.

He “hit” sixth in a family order that included six brothers and four sisters. The family relocated to Seattle when Dewey was six years old, making the move in Angel’s fishing boat.

“During the next dozen or so years, I learned plenty about halibut,” Dewey told The Vancouver Sun.” I also learned about the Alaskan waters, which came in handy later.”

Dewey developed a life-long love affair with the sea, and practically the entire Soriano clan became skippers of one sort of another. Four of the six Soriano boys, in fact, eventually turned up owning master’s certificates.

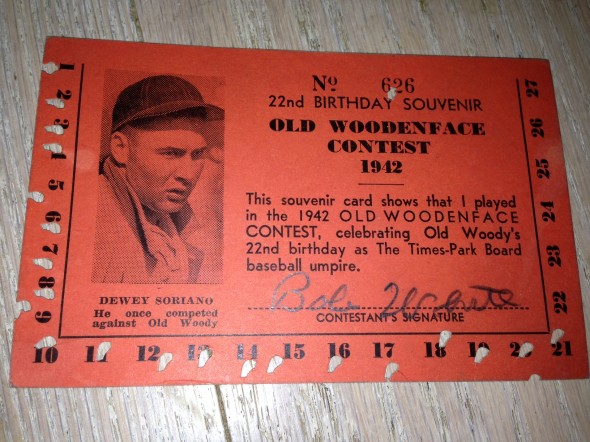

Soriano attended Emerson Grade School with Hutchinson and, as an 11-year-old, won “The Old Woodenface Contest,” an annual competition in which “boy pitchers” attempted to throw strikes from a mound through a wooden frame built to conform to the batter’s box. The competition, held at Rainier Beach Playfield, included Hutch.

“At Emerson, we won the last championship before Seattle grade schools quit playing baseball,” Soriano confided to Myers. “Fred Hutchinson was two years ahead of me, but in the sixth grade I was already the biggest kid in school (6-foot-3). Fred and I swapped innings, pitching and catching.

“At Franklin High, I played first base and the outfield the first couple of years until Fred graduated. Then I pitched for two years and lost one ball game. I can’t remember to which team, but it must have been Lincoln.

“Norm Dalthorp was the big hitter and Lincoln won the championship. That was the only one of my four years that Franklin didn’t win the championship.”

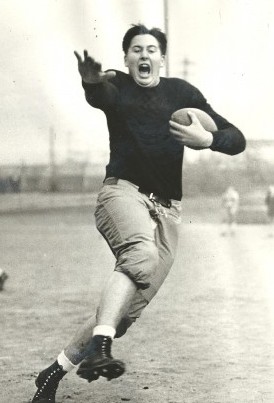

Soriano didn’t confine his athletic pursuits at Franklin just to baseball. He also starred in football and basketball. When he graduated from high school, he wanted to attend college, preferably at the University of Washington as brother Max subsequently did.

But the Seattle Rainiers made him a decent offer — $2,500 for signing and a percentage of anything the club might get in the event that it sold him to a major league team, and Soriano felt he couldn’t refuse such a windfall.

After signing his first pro contract in 1939, Soriano frequently said, “Baseball was always better to me than I was to baseball.”

Soriano went 0-1 with an 11.14 ERA in his first year with the club (nine games, one start) and barely played (2.0 innings) in 1940, owing to a spring training accident in which he tripped over a sprinkler head while playing catch and tore the cartilage in his right knee. An operation sidelined him for nearly a year.

“The next year, after I reported, I kept crossing up the catcher because his signals were indistinct,” Soriano said. “One day, before a game, the guys were amusing themselves by reading the names on the box seats. I couldn’t even see the box seats.

“Earl Torgeson, my roommate, wore glasses. I said to him, ‘Let me see your glasses, Torgy.’ Wow, I saw things I didn’t even know existed. It’s a wonder I hadn’t killed somebody, throwing blind.

“The next year I had a low draft number, so I shipped out in the Merchant Marine. I was gone four years, got back in 1946 and tore up my other knee sliding into a base. Seattle sold me to the Pittsburgh Pirates for $35,000 and my percentage was $10,000. I always remembered that, and when I got to be a general manager, I always gave a player a cut of whatever we sold him for.”

Starting as an able seaman, Soriano acquired his skipper’s papers within three years, a fantastic rise that, as Myers noted, “gives you a fair idea of the ambitious cut of Dewey’s jib.”

Being a mere 25 when the war ended, Skipper Soriano took another fling at baseball. As he noted, Pittsburgh purchased him for $35,000 and he reported to the Pirates’ spring training camp in 1947, hoping to follow his former Emerson/Franklin High teammate Hutchinson into the major leagues.

”I don’t know just what happened,” Soriano said. “I pitched real well, I thought. I shut out Boston and Baltimore and beat the St. Louis Browns, but they (the Pirates) had me shipped to Indianapolis when the season started.

“Then the Pirates sent me to (AA) Oakland, where I pitched for Casey Stengel. I hurt my arm there and could begin to see the writing on the wall. A pitcher who can’t see, has two carved up legs and a sore arm has to do some self examination.

“Finally, I was sold to Sacramento, but Sacramento wouldn’t accept a pitcher so full of patches. So I wound up pitching for San Francisco.”

In the summer of 1948, Soriano compiled a 6-2 record for the Seals while working as Lefty O’Doul’s (managed the Seattle Rainiers in 1957) top reliever, but quit his job – he made $1,500 per month – because, as Dewey put it, “I didn’t feel like was earning my money.”

Before Soriano departed the Bay Area for Seattle, Charles Graham, president of the Seals, called and proposed that he set up a farm team in Yakima on San Francisco’s behalf. Graham wanted Soriano to run the franchise, but the deal fizzled when Graham died suddenly.

“I had never thought of myself as a businessman,” Soriano told Myers. “All the time when I was a kid, Babe Ruth was my idol and a thought of myself as becoming a great hitter with the Yankees. Once, I led my high school league in home runs, which proves the league couldn’t have been too hot. “

Soriano thought the Yakima idea had died with Graham, but a short while later, Soriano received a call from Charles Graham Jr., who not only wanted Soriano to run a farm club in Yakima, but become part owner. Recognizing that the end of his playing career was coming, Soriano borrowed most of $15,000 from his brothers and bought 25 percent of the club.

Fred Mercey, a Yakima businessman, also purchased 25 percent, leaving the Seals with a 50 percent stake. Instead of returning to Seattle, Soriano moved to Yakima as part owner, president, general manager and star pitcher, and had a nice little run.

Soriano’s Bears won the Western International League pennant in 1949 as he went 14-2 with a 2.30 ERA. The Bears won the championship again in 1950 as Soriano posted a 6-2 mark in 20 games.

At that point, Soriano, who had helped the Bears increase their season attendance from 70,000 in 1948 to 155,000 in 1950, decided it was time to sell his interest in the Western International League team.

“I am leaving happy in the thought that I have never been a loser financially as the club’s president or as a pitcher on the home field,” Soriano told the Yakima Herald.

After relinquishing his interest in the Bears, Soriano returned to Seattle for the season’s final month and went 1-1 with a 2.40 ERA in seven games, all in relief.

“The next year (1951), I was back with San Francisco (after his Seattle release by manager Rogers Hornsby) but I felt I was not doing a good enough job (9.00 ERA in nine appearances) for the money they were paying me. So I asked for my release,” Soriano said.

That put an end to Soriano’s 10-year career as a professional player. Appearing in 208 games, Soriano won 58, lost 41 and produced a 4.01 ERA in 876.0 innings. He made 72 starts, threw 33 complete games and had four shutouts.

Given his executive experience in Yakima, Soriano easily could have gravitated to another baseball job. Instead, the 28-year-old figured it was time that he headed back to sea, and signed on as a third mate on the SS Alaska of the Alaska Steamship Company.

Soriano had a practical reason for his decision to opt out of baseball. His seaman’s license was due to expire under a five-year inactivity regulation and, with an eye on a seafaring future, he figured it was in his best long-term interests to put baseball on hold.

Soriano, who eventually became president of the Puget Sound Pilots, an organization responsible for maneuvering freighters and other large vessels entering and departing Puget Sound, stayed away from baseball until 1952, when, while on a training ship studying for his pilot’s license, he received a telephone call from Emil Sick.

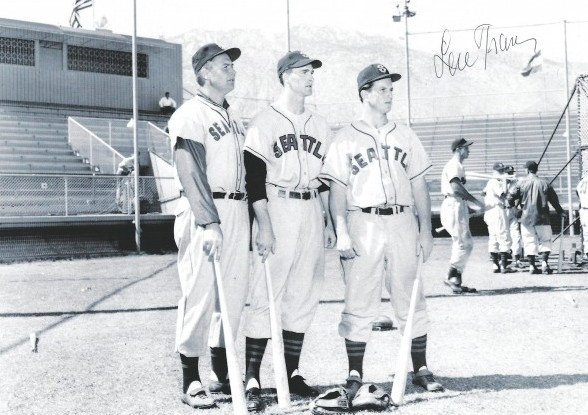

“Emil asked me to go to the Rainiers farm club in Vancouver as general manager,” said Soriano, who succeeded Robert Brown after Brown became president of the Western International League. “Then, on a Sunday in September, 1953, he called me to meet with him in Seattle the next day.”

That meeting led Soriano into accepting Sick’s offer to become general manager of the Rainiers, a franchise for whom he had once sold peanuts. Soriano had just turned 33 years old.

Two years later, the Rainiers, having stumbled under manager Jerry Priddy (77-85), Soriano prevailed upon his old friend Hutchinson to return to Seattle and manage the club. Soriano made a wise choice.

Hutchinson orchestrated a 95-77 record, the Rainiers won their first pennant since 1951 and Soriano was named Minor League Executive of the Year, in large part because the ball club drew 341,000 fans, more than doubling the team’s attendance total in 1954.

“Hutch won that for me,” Soriano said modestly (see Wayback Machine: Hutch & The 1955 Rainiers).

During the 1955 season, Soriano launched a public campaign for the construction of a facility that, 20 years later, would change the history of Seattle’s professional sports: a domed stadium. “It wouldn’t be a luxury,” Soriano argued to anyone who would listen. “It’s something we need.”

Virtually no one agreed, and Seattle newspapers slapped him around for more than a year for what they believed was his absurd conviction that Seattle required a facility for indoor baseball. Nobody had ever heard of indoor baseball (the Houston Astrodome was nearly a decade away). But by 1956, Soriano had won a few converts to his cause.

“Dewey Soriano has an idea that tops everything,” Hy Zimmerman penned in The Times Aug. 29. “He proposes a roofed stadium for Seattle and the Puget Sound area. It’s a big idea – the structure would be a domed double-decker to seat 60,000 or more spectators for football, baseball, basketball, hockey, national political conventions and religious conclaves.

“Dewey thinks the idea is big, but that the area is equal to the wish and thought. Dewey says, ‘This is the best place in the world to live. Why can’t we have the best facilities. It’s the age of science.

“There are materials to make a roofed stadium commonplace and those Boeing jet transports will put Seattle just a few hours away from big-league sports,” Dewey explained. “We can have all of them. With a roofed stadium, there would be no baseball rainouts and you can watch pro football snugly.”

Soriano admitted to Zimmerman that a domed stadium would cost a lot, but argued, “We must think in terms of the years ahead. There will be 1.5 million people in the Puget Sound area in 10 or 15 years.

“It (domed stadium) would have to be done with public bonds, but with an all-year program (of sports and other events), the structure would amortize itself fairly fast.”

In 1956, only Soriano talked about what would eventually (20 years later) become the Kingdome. He was eerily correct about the capacity (60,000), method of financing (public bonds), and range of events the facility would host.

The Sonics were still more than a decade away, but they played several years in the Kingdome. So did the Seahawks (beginning in 1976) and Mariners (1977). By the time of its implosion in 2000, the Kingdome had also hosted rodeos, motocross races, paper airplane contests, rock concerts and even religious conclaves – just as Dewey envisioned.

Soriano failed – at least publicly – to anticipate the rise of professional soccer in Seattle, and he missed the mark on the location of the domed stadium.

“I don’t care where it is put as long as we get it,” Soriano said.

Soriano figured the best place to site the dome was where Sicks’ Stadium had stood since 1938, when Emil Sick built his namesake park to house the Seattle Rainiers.

”Putting it there would be a shortcut to reconstructing the park,” Soriano argued to Zimmerman.

“I’ve spoken to Mr. Sick and he has said he won’t stand in the way. There is room to expand behind right field, out to McClellan Street. In left field, we could build seats right over Empire Way and traffic could flow underneath.

“Sicks’ Stadium is easy to access, near arterial highways and the floating bridge. There is a lot of room for additional parking. I’m not talking luxury here. I’m talking necessity.

“Why should a Seattleite get less of sports than someone in Kansas City or Cincinnati or St. Louis? We’re just as big and now – with the jet age – just as near.

“Remember, we lost the Rocky Marciano-Don Cockell title fight (held May 16, 1955 at Kezar Stadium in San Francisco) because we had no place to hold it. We must have a stadium, one that will match in beauty and size the area we live in.”

Soriano ultimately got the domed stadium he wanted, allowing him to bring major league baseball to Seattle for the first time. Ironically, and through no fault of his own, stadium issues and blundering city politics would prove to be his undoing and send him back to the sea again.

(Part 2 of the Dewey Soriano story will be published Tuesday, April 23, on Sportspressnw.com).

—————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com