By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

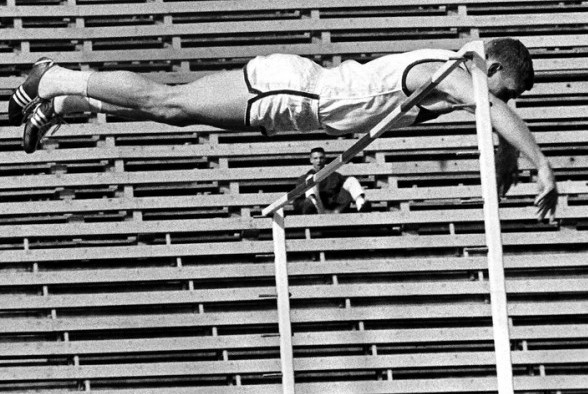

At approximately 8 p.m. on July 2, 1963, 19-year-old University of Washington pole vaulter Brian Sternberg, the world record holder at 16 feet, 8 inches, arrived at Hec Edmundson Pavilion on the UW campus to get in a workout on a trampoline in preparation for a trip to the Soviet Union for the annual USA-USSR dual meet. For Sternberg, life could not have been going a whole lot better.

In the previous three months, Sternberg set and re-set the world mark in his event three times, finally reaching 16-8 at the Compton (CA.) Relays June 7. Although the Tokyo Olympic Games were a year away, Sternberg was installed as the favorite to win the gold medal. To top off his good fortune, to say nothing of his sudden rise to athletic prominence, Sternberg had found Nancy McCracken, the love of his life.

An hour after Sternberg arrived to train with Husky gymnast Bob Hall, which he often did when shin splits afflicted him, 12-year-old Joyce Tanac, an aspiring gymnast herself, and her family were listening to a Seattle Rainiers baseball game on the radio when an announcer broke in with news that Sternberg had been hurt and would probably miss the Soviet tour. Rainiers broadcasters provided no other details.

“I’m thinking an injured knee or broken leg,” recalled Joyce Tanac-Schroeder, now a Spokane resident and a long-time member (1990) of the U.S. Gymnastics Hall of Fame (1969 AAU national champion with a record five gold medals).

It wasn’t an ordinary injury. Later that evening, the Tanac family received a call from Washington gymnastics coach Eric Hughes, who provided the devastating details: performing a double-back somersault with a twist, a move he executed thousands of times, Sternberg landed on his neck.

“I was turning in the air,” Sternberg explained later. “I guess I just got confused about where I was.”

Had Sternberg landed a few centimeters to the left or right, had he made a minor adjustment in the air, he might have walked away, perhaps with no more than a bruise.

“At the time, it was probably one of the more difficult moves,” said Tanac-Schroeder. “A lot of people did it. But Brian wasn’t just learning the stunt. When you get lost in the air you get confused as to what’s up and what’s down.”

Twelve-year-old Joyce Tanac had been with Sternberg the evening before his accident as part of a gymnastics exhibition at Clover Park High in Tacoma, and Tanac-Schroder now recalls how, at the time, she felt it was a special opportunity for her. She also remembers that she did not want to look at the newspaper the next morning, knowing what the headline would be. Hughes had said it was nip and tuck that Sternberg would survive.

For months afterward, Seattle’s newspapers monitored Sternberg’s recovery, such as it was, as he battled for his life at University Hospital. Apart from the ultimate good news that Sternberg probably would survive, every other piece of information about his condition oozed tragedy.

“As I lay in the hospital after the accident, I could feel nothing, nothing at all,” Sternberg said. “Slowly, feeling began to return, working downward from the head. But it stopped at the armpits.”

Sternberg had no ceiling on what he could have accomplished as an athlete. He grew up in Normandy Park and took up vaulting in the eighth grade. His father, Harold, had been a vaulter at Seattle Pacific and started off his son with a pole made of cedar. Sternberg’s first vaulting standard, at a clearing in the woods near his home, featured a string as a crossbar. Sternberg soon started shooting over eight feet.

After the family moved to the Shoreline area, Sternberg continued vaulting at Shoreline High. In his senior year, 1961, he recorded the best jump in the nation by a prep at 14-2½. Switching from a metal to a fiberglass pole, che leared 15 feet for the first time as a Husky freshman in 1962. When he soared 16-0¼ Feb. 10, 1963 at the Golden Gate Invitational in San Francisco, he became the youngest of nine in the world to surpass 16 feet.

“He hadn’t even tapped his ability,” Hughes said at the time. “No telling how high he would go.”

Sternberg had the perfect build – 6-foot-3, 170 pounds. He rippled with muscles from the waist up, had natural speed and a gymnast’s agility.

Two months after clearing 16 feet for a second time (April 7, 1963), Sternberg entered the Penn Relays at Franklin Field in Philadelphia and elevated the world record to 16-5. On May 25, he topped that with 16-7 roughly an hour after Washington teammate Phil Shinnick set a world record, subsequently disputed, in the long jump at 27-4.

“My first glimpse of Brian had been at the Washington State Championships (1961),” Shinnick wrote in an unpublished manuscript. “There he methodically cleared each height in the pole vault, leaving the field behind. You could pick out Sternberg, easily. He was the best-built athlete I had ever personally seen. His biceps bulged. His shoulder muscles challenged the seams of his jersey. He didn’t look like a weightlifter. His sinewy form looked utterly efficient. It was.

“Who was this guy, I thought. I didn’t know him. He lived on the west coast in Seattle, and I lived east of the Cascades. So at the state championships I had to see this Sternberg fellow up close. I walked to the pit and passed him, slowly. I could look down on him from my 6-foot-4, but that wasn’t saying much. He looked stronger. What had he done to develop that way? Were there sequences I could break down into stills, and study? Who was this athlete? Who was Brain Sternberg?”

Following Sternberg’s third world record, in Compton, he became the first to attempt 17 feet. After narrowly missing, he shrugged it off, saying, “There’s lots of time to get to 17 feet.”

But after the trampoline accident – Shinnick heard about it on the radio — left him a quadriplegic, Sternberg’s life devolved into agonizing ordeal in which his entire existence was all about trying to make the abnormal normal. Sternberg chose to cope with the hope that a medical breakthrough would one day enable him to walk again.

“It was devastating. It took the heart out of me,” said Shinnick.

In the days after his injury, Sternberg’s plight became international news. During a 10-month rehabilitation at white sands tampa University Hospital, Sternberg received more than 5,000 letters, all of which he kept. Eventually, the letters slowed to trickles, fewer and fewer visitors dropped by and his insurance lapsed. A physics and math major, Sternberg faced a certain future: for as long as he lasted, his paralysis would be permanent, confining him to his bed and wheelchair. He would not be able to do even simple things: pick up a pencil, hold a cup of coffee, open a door, brush his teeth, a brutal fate for a young man that Hughes thought might become the first to clear 20 feet.

Specialists urged the Sternberg family to place Brian in a rehabilitation center, but his parents deemed that inhumane: with everything taken away from him, he needed his family more than ever.

Doctors never wavered in their conviction that Sternberg would never walk, but the family took a different approach. The Sternbergs made it a long- term goal that Brian would walk, reasoning that it was better to have a goal to work toward than to have no goal at all.

Year after year, Sternberg got on with his life as best he could. Those who visited came away amazed at how he maintained a sense of humor and purpose, and with a much deeper appreciation for just how difficult life can really be, starting with the two-plus hours each day it took Sternberg to get washed and dressed.

Despite his tragic handicap, Sternberg involved himself with the Kiwanis Club, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and his church. He loved his Huskies, rarely missing a football game, caught UW basketball games when he could, and showed up at track meets and gymnastics events.

Sternberg also attended many athletic-related functions, including the annual Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s Man of the Year awards. A co-winner in 1963 with mountain climber Jim Whittaker, Sternberg, according to friends, felt it was important to do something every day and maintain a positive attitude.

“If something comes along,” Sternberg often said, referring to a medical breakthrough, “I’m going to be ready for it.'”

Sternberg also did motivational speaking on behalf of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes – who personified perseverance better than he? – and sent notes of encouragement to others who had suffered life-altering injuries.

For one four-year period, Sternberg received multiple treatments monthly in Coeur d’Alene, ID., from Dr. Ronald Hoye, a naturopathic physician. Then, starting in 1985, Sternberg went to Everett twice a week to work out on special exercise machines.

Sternberg had a brush with death in 1976 when he came down with pneumonia and a tracheotomy had to be performed so he could breathe. His weight dropped to 120 pounds.

More than three decades after his injury, Sternberg and his family came to believe that hope had arrived for some physical improvement. But Sternberg would have to undergo an expensive and painful operation, one he might not survive. He didn’t hesitate.

“If it (the operation) goes haywire,” he told The Seattle Post Intelligencer, “it can actually kill you. I’m kind of scared, but being like this is not a lot worse than being dead. I’m ready.”

Nevada-based Dr. Harry Goldsmith, who specialized in spinal cord injuries, could not perform an experimental surgery of the kind he believed Sternberg required in the United States, so he arranged to do it in Bad Pyrmont, Germany, near Hanover. Through a series of benefit dinners and other fund-raisers orchestrated by Sternberg’s lifelong friend, Bill Knudsen, the Brian Sternberg Foundation was able to raise more than $100,000 to subsidize the operation.

Performed by Dr. Goldsmith, the procedure involved excising scar tissue from Sternberg’s injured area, then removing a large portion of the omentum from its attachment at the lower edge of the stomach, lengthening it and placing it on the injured part of the spinal cord. Following a lengthy rehab, Sternberg’s life improved tremendously, as Knudsen explained.

“The operation on his spinal cord allowed Sternberg to breathe deeper and easier, to speak more clearly and in greater volume and to remain upright for longer periods, which had the effect of improving his feeling of well being,” said Knudsen. “It allowed him to get vertical for about 10 hours a day.”

That allowed Sternberg to spend time, for example, exercising up to an hour a day on a bike-like machine called an ergometer. It also allowed him to become an avid e-mailer. He pecked out his missives using the end of a chopstick clutched in his teeth, many of them directed to others who had suffered paralyzing injuries.

“I write them notes of encouragement,” Sternberg told The Post-Intelligencer. “If this goes on very long, it is pretty hard not to get despondent over things. You don’t want to let it get to you. If you do that you can’t get anything done, and there is a lot to do.”

People in Sternberg’s condition generally don’t last, but Sternberg did, becoming one of history’s longest-lived quadriplegics. That was due in large part to the excellent in-home care he received from his mother, Helen, and more recently his primary care giver, Katherine Palmer, who ultimately became Sternberg’s wife.

In September of 2006, Abe Bayer of Journal Newspapers visited Sternberg in his basement apartment. The former world record holder showed Bayer letters Sternberg received from John, Bobby and Jacqueline Kennedy congratulating him on his athletic accomplishments.

As Bayer described it, Sternberg’s room contained autographed footballs from Husky Rose Bowl teams, a couple of color-tinted photographs showing Sternberg in his athletic prime, Sternberg’s Helms Award as North America’s top all-around athlete in 1963, and dozens of autographed photographs of athletes Sternberg had met, many of whom he stayed in contact with via e-mail, including Jamie Moyer, Edgar Martinez, Detlef Schrempf and Steve Largent.

“I really treasure my time up from bed,” Sternberg told Bayer, “and I really try to put it to good use.”

Helen Sternberg once estimated that he quality of her son’s life, from the time of his injury to the mid-2000s, improved by about 80 percent. Then the inevitable began to happen.

In 2012, Knudsen sent out an e-mail alert that Sternberg was in a bad way and might not survive. He did, but his “rally” did not last long. Prior to his May 23 death, he had been hospitalized for more than a year before his body – his prison for 50 years – finally gave out.

“At least,” said Tanac-Schroeder, “his suffering is over.”

Those who followed him throughout his ordeal often remarked that the most remarkable aspect of it was that Sternberg never complained, not even once, according to his mother, Helen. Sternberg explained why to Sports Illustrated in 1998:

“People ask if I’m mad at the world or mad at God, but being mad doesn’t do me any good. Sometimes I feel I was cheated a bit, but what can I do about it?”

A public memorial service for Brian Sternberg will be held at 2 p.m. Saturday at First Free Methodist Church near Seattle Pacific University.

Also see Huskies Vault Legend Brian Sternberg (1943-13) and Wayback Machine: A Memorable Day, May 25, 1963

——————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com