By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

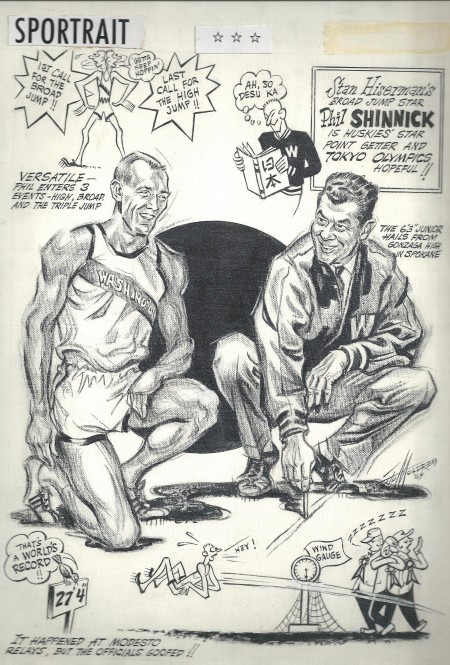

One day after shocking the track and field realm with his May 25, 1963 long jump of 27 feet, 4 inches at the California Relays, University of Washington sophomore Phillip Kent Shinnick, a month shy of 20, still couldn’t believe he had practically leaped the width of a city street, or that news of his feat had circled the globe.

“There was excitement in the air,” Shinnick wrote in an unpublished manuscript that recalled his ‘Modesto Miracle.’ “Peter Snell had just won the mile and Bob Hayes won the 100 in 9.3 seconds. I knew I had a good jump. I thought maybe 25½ feet. I stood by the pit while they reeled out the steel tape. I saw 25 feet, then 26, and I began to feel giddy. When 27 came out, I almost fell over backwards.”

For busting Igor Ter-Ovanesyan’s world mark of 27-3¼, Shinnick was voted Athlete of the Meet, which also included Hayes Jones’ 13.4 hurdle victory over Blaine Lindgren by a tenth of a second and Al Oerter’s 202-11 discus win over Jay Silvester, who hurled 201-10½.

But soon enough Shinnick learned of a snafu. With red faces, meet officials confessed that when Shinnick jumped no official monitored the wind gauge. More than that, long jump officials had specifically been told to watch the gauge only when defending Olympic champion Ralph Boston took his turn.

Their awkward reasoning: they never figured that nobody but Boston could break Ter-Ovanesyan’s record, and that taking a wind reading for any other jumper amounted to a waste of time.

Moments before Shinnick’s shocking effort, Boston jumped 26-6. The gauge was under scrutiny and velocity under the maximum. Even after Shinnick, on his first leap, sailed a prodigious 26-10, barely ruled a foul because he overstepped the takeoff board, Modesto officials still put nobody on the gauge. They never adequately explained that lapse.

The meet referee, Charlie Hunter, said Shinnick’s performance would have to be recorded as “wind aided,” due to the fact variable winds during the evening had maxed at seven miles per hour, well above the allowable 4.473. But at the moment of Shinnick’s leap, the wind had died to nothing, according to numerous witnesses, including Boston.

Bob Lynch, head inspector at Modesto, explained that Shinnick’s leap occurred during the junior college low hurdles race. The only wind gauge available was used on that event.

“The maximum wind during the low hurdles was 3.90 mph and this is additional evidence that Shinnick’s jump was not wind-aided,” said Lynch.

“First of all,” wrote Arthur Robinson of the Sacramento Bee, “it wasn’t a wind. It wasn’t even a breeze. Nor was it a zephyr. Even a hummingbird’s feather would have dropped to the ground without drifting in its descent at the moment young Shinnick made his phenomenal jump.”

Just prior to Shinnick’s turn, teammate Brian Sternberg tested the wind with a tried-and-true method used by all athletes: he plucked blades of grass and tossed them in the air. They fell directly to his feet. No appreciable wind.

“There is no reason in the world why the record shouldn’t be recognized,” said Dr. Hilmer Lodge, an AAU official. “I was there and can testify there was hardly any wind.”

Dr. Leon Glover Jr. found himself the man in the middle. He was supposed to have taken the reading – but didn’t, on orders.

“I can’t justify my position, obviously,” said Glover. “But ever since I’ve been doing this, I’ve been bothered that I can’t find an official who has knowledge of the rules. If I had known about Shinnick, I would have taken a reading. It’s that simple. But I’d never so much as heard of him.”

After a review the next day, Modesto officials voted the to accept Shinnick’s 27-4 as a legal jump and submit it for ratification, first to USA Track and Field, which would then, presumably, send it along to the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF) for final approval.

But in an extraordinary non-move, they never did.

Hours before his 27-4, on the morning of May 25, 1963, Shinnick established a personal best of 26-6 at the Big Six Championships in Berkeley, only to have an official red flag the jump – not because Shinnick scratched, or did anything illegal, but because the official believed Shinnick “lost his balance” – a judgment call.

Shinnick argued that judgment calls didn’t exist in track and field, but got nowhere. Following his 26-6, Shinnick had one more attempt. His coach, Stan Hiserman, told Shinnick to run down the left side of the runway where he had placed a mark two feet behind the board since he was three feet ahead of the next competitor. Officials hadn’t raked that side of the pit and when Shinnick landed his heels hit hardpan. He slid and landed on his back and the measurement from his shoulders was 21-5, not enough to make the finals by an inch.

Robbed in Berkeley, Shinnick’s seething mood transformed to giddy after going 27-4, and then to despair after he learned no one had monitored the wind gauge.

“It was the greatest day of my life – and the worst,” said Shinnick.

——————————————

When Spokane native Shinnick enrolled at Gonzaga Prep, he stood 5-foot-6. But he possessed incredible speed and athletic ability and, despite what they say about white men, could jump (at 5-foot-6 he could touch the basketball rim). He made the first team as a point guard.

“I could run circles around everyone or jump over the tall guys,” Shinnick wrote. “I loved to charge the center and hang in the air and, at the last minute shoot, double and triple scooping. The coach didn’t like this because it made me look so good and he didn’t think that players should be so flamboyant.”

By his junior year, Shinnick has spurted to 6-foot-4, making him the tallest guy in the school. Although Shinnick wanted to play guard, the coach made him the center. Shinnick dunked easily.

Until the night of his senior prom, Shinnick seemed destined to become a basketball player on the collegiate level. He received a scholarship from Washington State, which he accepted. But while motoring home from the prom, Shinnick was involved in a collision that pitched him through the windshield. He emerged with his right hand banged up. Nobody was going to play basketball with that hand for a while, so Shinnick forfeited his scholarship and accepted a track ride to Washington.

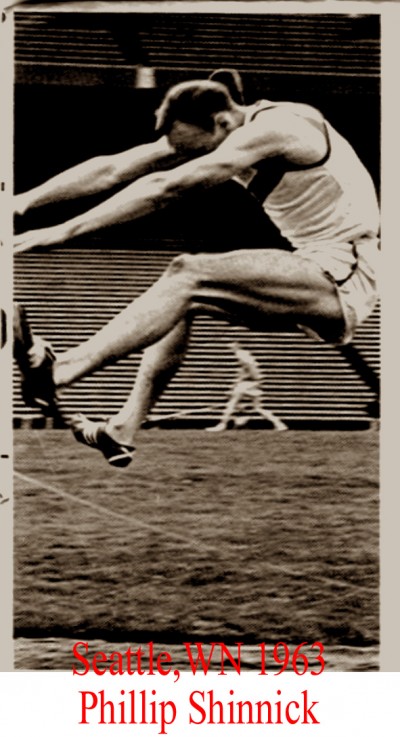

The Washington state long jump champion in 1960 and 1961 (jumped 23-1 as a senior at state), Shinnick had an immediate impact on Washington’s freshman team. In his first college meet, Shinnick scored 18 points in a 68-63 win over Vancouver’s Olympic Club, winning both hurdle races, the long jump, and finishing second in the high jump.

He had his first big breakthrough in a dual meet with Oregon in the early spring of 1963, jumping 25-2. A week later, at the Far West Track Championships in Pullman, he soared 25-5. Then came his red-flagged 26-6 in Berkeley, followed by the “Modesto Miracle” at 27-4.

Shinnick never again jumped within six inches of his one-shot shocker, but had an outstanding collegiate career, during which he became determined to prove his Modesto mark hadn’t been a fluke. He more than succeeded.

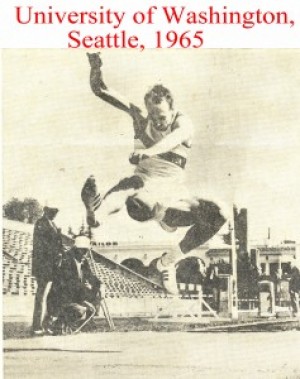

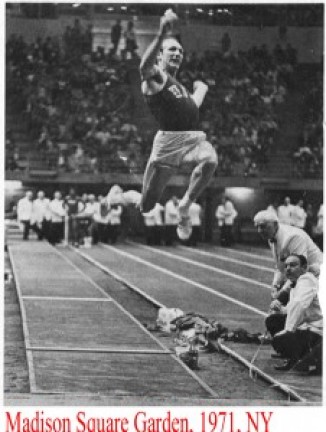

Typical of Shinnick’s skill set was an indoor meet Nov. 21, 1963, when he won the high jump at 6-5½, the 70-yard hurdles in :08.5, the long jump at 23-8¾ and the 300-yard low hurdles in 33 seconds flat. Two years later (April 17, 1965), in a 78-66 dual meet win over Oregon State, Shinnick won the long jump at 25-1, the high jump at 6-6, the triple jump at 46-3¼, and placed third in the 100 in 9.9.

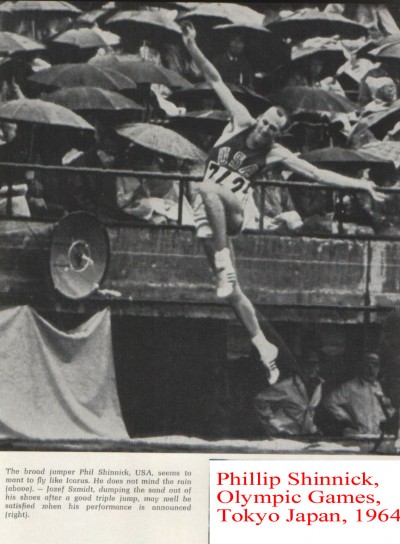

In three varsity seasons, Shinnick scored 186 points – 35 in 1963, 80 in 1964, 71 in 1965 — making him the highest point scorer in UW history. He also made the 1964 U.S. Olympic team. Competing in a rainstorm on a muddy runway with shifting winds that caused him to foul on two jumps with wind at his back and another headwind in his face, Shinnick soared from well behind the board on his last attempt. His 23-9¾ didn’t quite qualify for the finals.

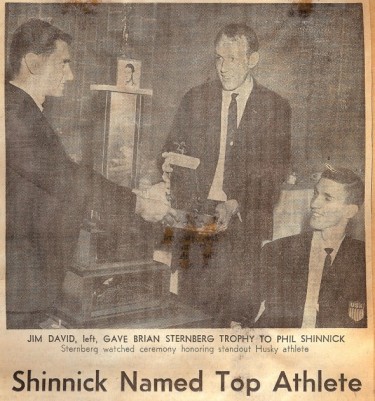

In 1965, Shinnick became the second recipient of the “Brian Sternberg Award,” named for Shinnick’s former teammate who had been paralyzed in a trampoline accident July 2, 1963. Presented by the Associated Students of the University of Washington, the award went to Shinnick for best exemplifying the qualities of “faith, courage, inspiration, sportsmanship and competitive performance.”

Shinnick smiled when he received the award from 1964 winner, gymnast Jim David, but was not an entirely happy young man.

“When I graduated, I felt so disgusted,” said Shinnick. “I’ve always felt as an athlete that records are important. I wanted to break American and world records from the time I was a little kid. Everywhere I competed I wanted to break a record. As athletes, that’s what we try to do. I was capable of being a world record holder.”

Shinnick wrote letters to U.S. track and field officials for more than two years requesting a re-examination of May 25, 1963. Mostly, he was ignored. While Shinnick never gave up on his pursuit of justice, he admitted, “The more I worked at it, the less I cared about it.”

For the next several years, Shinnick let his performances speak for him, and they orated loudly. Already a 27-foot long jumper, Shinnick officially became a seven-foot high jumper in 1966 when he cleared 7-0½.

A year later, Shinnick made the U.S. National Team in the decathlon, scoring a record total for the first day, and finished with more than 7,000 points the first time he attempted the 10 events. A year after that, Shinnick long jumped 26-9½ at Flagstaff, AZ., against the German Olympic team, fourth-longest ever by an American. He was voted captain of the 1969 U.S. National Team for that year’s Pan Conference Championships in Japan and won a silver in the high jump and bronze in the 4×100 relay.

Shinnick, who made the 1968 Olympic team as an alternate at 26-6½, remained a world-class competitor through the early 1970s and had hopes of making the 1972 Olympic team after jumping, at age 29, 26-5½. But he suffered an injury just before the Munich Games, effectively ending his track exploits, but not his athletic career.

Shinnick ran marathons and 10-K races until he was 50, and then joined a tri-athlete swim team for 15 years. He also did yoga for 40 years and gung fu for 20.

—————————————-

After leaving the University of Washington with an economics degree, Shinnick enrolled in graduate school at the University of California to study social psychology. It was during his time there that he befriended the controversial Jack Scott, who served on Shinnick’s Ph.D Orals Committee and then ultimately became associate director of Scott’s “Institute For the Study of Sport and Society” from 1969-72.

They published five books by athletes, including Dave Meggysey’s Out of Their League, Gary Shaw’s Meat on the Hoof on the hidden world of Texas high school football, and Paul Hoch’s Rip Off the Big Game, among others.

Forty years ago, Scott was a “sports activist” who believed that athletes, particularly black athletes, should rebel against what Scott insisted was the “inhumane and depersonalizing attitudes of coaches and athletic administrators.” Scott wrote a book titled Athletics for Athletes, later revised and re-titled, The Athletic Revolution. Many sports columnists recommended it as required reading, along with The Revolt of the Black Athlete, by Scott’s Bay Area colleague, Dr. Harry Edwards.

Long before Title IX, Scott argued for equal treatment of women athletes. He believed in hiring minorities to important athletic department positions, and condemned the “evils of win-at-any-cost football.”

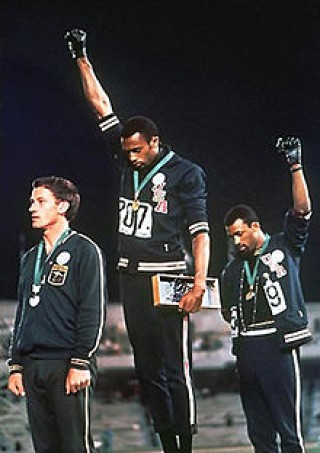

Many considered Scott and his wife, Micki, radicals and kooks. But basketball star Bill Walton didn’t, nor did Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who irked the establishment by lifting gloved fists from the medals podium at the 1968 Olympics.

Neither did Shinnick. In fact, in 1971, when many of Scott’s ideas were gaining acceptance, the University of Washington, whose football program had been awash in racial turmoil for several years, offered him an assistant professorship in women’s physical education.

Scott accepted. However, fear of his possible destructive influence prevailed and, under heavy pressure from the UW faculty, the school withdrew the job offer. Scott sued and settled out of court for $10,500.

At about that time, Shinnick, now with a Ph.D. in social psychology, relocated to Piscataway, NJ., where he first became director of sports studies at Livingston College, part of Rutgers University, and then an assistant professor of history and sociology. After four years, Shinnick found himself back in the headlines, not as a track competitor, but as a friend and alleged co-conspirator of Scott’s.

The FBI believed Scott and Micki helped Patty Hearst, newspaper heiress turned Symbionese Liberation Army bank robber, elude federal authorities in the summer of 1974 by hiding her on a farm he rented in South Canaan, PA. The FBI thought Shinnick might have abetted.

In April, 1975, a federal grand jury in San Francisco subpeoned Shinnick to tell what he knew. Shinnick told the grand jury he had nothing to hide, was not guilty of any crime, and that he had never set foot on the South Canaan farm.

Tom Wicker of The New York Times summarized the hearing: “Shinnick did not refuse to answer questions. He did not refuse to give the grand jury any evidence that it required for its own deliberations. He refused, instead, to give the FBI his fingerprints, samples of his handwriting and clippings of his hair. The FBI suspects Shinnick of having been involved in, or at least knowing something about, the alleged harboring of Patty Hearst. The Shinnick case is one more in a lengthening pattern of blatant government use of grand juries for inquisitorial rather than accusatory purposes.”

The feds imprisoned Shinnick in 1977 for two months at Allenwood, PA., for failing to cooperate with the investigation, and Rutgers suspended him and reduced him to half pay. Ultimately, the FBI had nothing on Shinnick and he was never charged with a crime.

Later, Dan Rather, the CBS news anchor, interviewed Shinnick on 60 Minutes on the subject of grand jury abuse. That led to Shinnick’s meetings with Benjamin Civaletti, head of the civil division of the Justice Department, and the American Bar Association. Congress ultimately passed laws to prevent perversion of the grand jury process by the FBI.

—————————————————

In the early 1980s, Thomas Monahen, executive secretary of the New York State

Board of Medicine, made a deal with New York Medical College: if it appointed Shinnick an assistant clinical professor of medicine, it would get a physicians training program for acupuncture certification. Later, Shinnick moved to the Research Institute of Global Physiology, Behavior and Treatment. After that, he spent seven years with the Heart Disease Research Foundation.

He became a senior researcher at the Rusk Institute of NYU and worked in a pain clinic for 15 years, treating difficult-to-cure patients. Shinnick was also named associate editor of the Journal of the Science of Healing Outcomes and contributed to the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. In 2009, with Adriano Borgna, Shinnick wrote a book, “Whole Person Healing: The O-Ring Imaging Technique Influences to Oriental and Occidental Medicine.”

Shinnick also authored popular pieces for The New York Times, Runner’s World, and for international journals and newspapers including Sovietski Sport and New China.

Working out a Park Avenue office and living in Manhattan’s Upper West Side, “Dr. Phil” put together a lengthy and impressive resume:

- Director, Institute for Global Physiology, Behavior and Treatment

- New York State Licensed Acupuncturist

- Member, New York Academy of Science

- Member, New York Society of Physician and Dentist for Acupuncture

- Member, US Association of Qigong

- Member American Chemical Society

- Founder and Chairman, Athletes United for Peace, 1984

- Goodwill Ambassador of UNESCO for Sport and Peace

Athletes United for Peace sponsored track and field competitions, road racing, soccer matches, and basketball games in the U.S. and overseas as well as community programs on both U.S. coasts.

But for all of his varied interests, that day in Modesto never left Shinnick’s mind.

“It changed my life fundamentally,” he said.

——————————————

In 1992, the University of Washington inducted Shinnick into the Husky Hall of Fame (Brian Sternberg entered in 1983), and an exchange during the ceremony made a profound, life-altering impact.

“I was there being honored and my dad look looked over to me and said, ‘Why are you so unhappy? I mean, here you all in the Hall of Fame at the University of Washington and 80,000 people honoring you.’ I said I was miserable because my jump was never recognized and I will never be happy about that. I realized that it had gotten down deep and under my skin. It really bothered me. My dad gave me the push to actually do something about it.”

The task Shinnick assigned himself had “Sisyphus” written all over it.

He took his case to the highest levels of track and field, soliciting and receiving support from Olympic gold medalists Lee Evans, Tommie Smith, Harold Connolly and Bob Beamon, among others. Ralph Boston, the man Shinnick beat in Modesto, signed an affidavit on Shinnick’s behalf. It said:

“I saw the attempt and it was real.”

UW athletic director Barbara Hedges wrote a letter to Ollan Cassell, executive director of USA Track & Field, dated Jan. 6, 1996, that also argued for restoration of Shinnick’s record.

With it, Hedges attached statements from numerous individuals involved in the Modesto meet, including director Tom Moore, wind gauge officials Leon Glover Sr. and Leon Glover Jr., head referee Bob Lynch, AAU official Cap Hanson, open meet referee Charlie Hunter, and Hilmer Lodge, director of relays.

“These officials had first-hand knowledge, saw the jump, were aware of the conditions of the wind, and gave public testimony and affidavits,” Hedges wrote. “In addition, our coach, Stan Hiserman, team captain Mike Thrall and Brain Sternberg watched the jump and were aware of the wind conditions. Tex Maul of Sports Illustrated said that there was, ‘not a breath of air stirring.’

“Just before the jump, Sternberg, Shinnick and Thrall dropped grass to test the wind. It dropped down near their feet and did not blow away. After Shinnick made his leap, Coach Hiserman interviewed all the meet officials and verified the legality of the jump, which confirmed his own observation. It was then accepted as a UW record.”

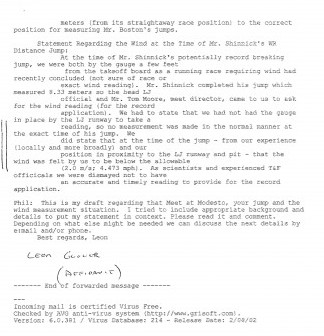

Glover Jr. best summarized the gist of the officials’ statements with his affidavit:

“At the time of Dr. Shinnick’s record-breaking jump, we were both (my father and I) by the gauge a few feet from the takeoff board as a running race requiring a wind gauge had recently concluded. Dr. Shinnick completed his jump, which measured 8.33 meters (27-4). The head LJ official, and Mr. Tom Moore, meet director, came to us to ask for the wind reading (for the record application).

“We had to state we had not had the gauge in place by the LJ runway to take a reading, so no measurement was made in the normal manner at the exact time of his jump. We did state that from our experience (locally and more broadly), and our position in proximity to the LJ runway and pit, that in our opinion the wind was below the allowable. (2.0 m/s; 4.473 mph).

“As scientists and experienced T&F officials, we were dismayed not to have a wind gauge reading to provide for the record application. However, we were able to accurately judge, from our senses and experiences, that there was no wind during the jump. Thus, it was our opinion then, and is now, that Dr. Shinnick’s jump at Modesto was legal and a world record.”

“All of the above reasons do not explain why ratification of Shinnick’s world record never came,” the Hedges letter continued. “The Cold War between the Soviet Union and U.S., and the mutual suspicions set the tone for fear and partially explain actions of your association. As Cap Haralson (head AAU official in California) said, ‘It will be a matter of taking something away from the Soviets, and the Soviets don’t give in easily.’ Igor Ter-Ovanysean held the record at 27- 31/4, but to deny an American a true record was and is a grave injustice.

“Shinnick defeated Ralph Boston . . . Peter Snell ran an American record in the mile and was .5 seconds from his world record . . . Sternberg broke the world record in the pole vault . . . Oregon State ran a new world record, and there were many top marks in the world at that meet. But overall, Shinnick was voted the Outstanding Athlete. This should speak to what 10,000 people saw.

“The fact that this record has stood at the University of Washington for over 30 years unchallenged, and that we followed the same procedure for acceptance that constitutes a world record in the long jump should make your job easier now. Injustice is never time bound. History should reflect accurately legal marks, especially ones that have survived the test of time.

“We urge you at long last to submit Phil Shinnick’s world record jump of 27-4 set on May 25, 1963 to the IAAF as an American record at that time.”

Cassell ignored Hedges’ letter.

During the pursuit to have his record recognized, Shinnick was often asked what possessed him. On one occasion, he said, in a statement picked up by The New York Times, “I’m doing this because of truth and justice. I want to be happy in my life and I don’t want to die while thinking about this. I don’t want to have regrets.

“When you get older that’s what happens to you. Things that were bad start to come back. So I don’t want that. I’m in medicine. I see a lot of people dying and I see how, if they don’t deal with things in their life, it bites them in the end and it makes them bitter. You’ve got to have peace and I want peace in my soul.

“Normally, when you’ve done well, you feel good. I didn’t feel good the next day, and I didn’t feel good for 40 years.”

———————

News of Shinnick’s historic leap made news around the world. For Shinnick, the most significant consumer was New Zealander Grant Birkinshaw, who watched Shinnick’s Modesto jump on a newsreel at a cinema, and who later explained to USA Track and Field’s Records Committee the impact it had on him.

“I had heard of Phil Shinnick and his jump as a youngster in Te Aroha, New Zealand, as it had made world news,” Birkinshaw said. “I was inspired enough by the performance to attend the University of Washington during the 1970s as a long jumper to further my own athletic and academic career.

“A further connection with Phil’s performance and New Zealand was that on that evening the featured event of the California Relays was the mile race between Peter Snell of New Zealand and Jim Beatty of Los Angeles. The race was billed as ‘The Mile of the Century.’ Peter Snell won the race in a record time, but even this feat was overshadowed by the performance of Phil Shinnick. It was his performance that gained the headlines, even in my own country.”

Birkinshaw did not meet Shinnick during his time at the University of Washington, but left behind one outstanding mark of his own – a 1971 freshman long jump record of 25-1 ¾, still the fifth longest, regardless of class, in Huskies history — before returning to New Zealand after his graduation.

Thirty-two years later, for no particular reason, Birkinshaw began to wonder what had become of Shinnick. Curiosity got the best of him and within a matter of hours he had a phone number for Shinnick in New York.

“I called, got his answering machine, and was leaving a message when he picked up the phone,” Birkinshaw told The New York Times. “It didn’t take me long to figure out how much the record still meant to him.”

Birkinshaw decided to take up the case. For the next few months, he and Shinnick examined press clippings, watched 16mm film of the event, researched weather reports at the New York Public Library, and sought affidavits from those who were in Modesto.

“We’ve got a robust case to get Phil his record,” Birkinshaw said after completing the research. “I hope they have a robust rebuttal.”

Identifying himself as “Coordinator of the Shinnick Record Committee,” Birkinshaw presented findings to USA Track and Field in Greensboro, NC., in early December, 2003. Birkinshaw emphasized these points:

- The rules in 1963 for having a world record ratified required signed affidavits from six meet officials attesting to the validity of the performance. This was not done at the time of Shinnick’s performance, but a search produced affidavits from all officials still alive, including Dr. Leon Glover Jr., who assisted his father on the anemometer that evening.

- Affidavits had been obtained from meet director Tom Moore, competitor Ralph Boston and pole vaulter Sternberg, all eyewitnesses. Film clips were viewed to determine wind effects on items such as flags and bunting. Photographs and newspaper reports were examined to gain an understanding of the conditions. Wind readings of track events that were on at the same time as Shinnick’s jump were examined.

Ralph Boston lost to Shinnick in Modesto in 1963, but submitted an affidavit saying Shinnick’s jump was legal. “I saw the attempt and it was real,” said Boston. / tnstate.edu

- The method of gauging the wind by Sternberg and Shinnick by dropping grass to the ground to gauge its strength, while unsophisticated, was remarkably accurate. After Sternberg did this he signaled Phil to commence his jump.

- The runway was lined with spectators on both sides. This provided a six-foot high-wind barrier, further breaking up wind assistance.

- The anemometer (wind gauge) used to measure the 220-yard low hurdles race recorded a legal wind at the exact moment Shinnick jumped.

- Ralph Boston’s jump for second place was legal, as were other jumps that were measured within the competition.

- Ground conditions and methods of measurement met the standards set down by the IAAF for world record purposes.

- A retroactive ratification would not displace any individual from the record list, only merely add one.

- A precedent, in fact several, for retroactive ratifications existed. Example: Nineteen years after Daniel Joubert of South Africa equaled the world mark in the 100 (yards) at 9.4 in 1931, he sought and received recognition from the IAAF for his achievement.

- At the time of Shinnick’s jump, it was not yet standard practice even for major meets to measure the specific wind for every jump of every jumper. (Shinnick’s jump changed that).

Boston drove to Greensboro from his home in Georgia to support Shinnick. Former Olympians Lee Evans and John Carlos joined them.

After weighing the evidence, examining documents and statements, and listening to witnesses, the Records Committee rejected Shinnick’s appeal.

The Records chairman told Shinnick they had to reject it because Birkinshaw and others claimed there was no wind at the time of he jump, yet evidence showed that the wind was at two mph and therefore not as they claimed, no wind — an oxymoron since two mph is legal.

Evans later interviewed young athletes on the Records Committee who said

they voted to support the record, but Bob Hersh, a USATF board member, told them they had no authority to do it and bullied them to say the decision to reject the record was unanimous. They gave no public statements.

But at the urging of John Chaplin, a retired Washington State track coach and a leading USATF official, the USATF Executive Committee agreed to a special session to reconsider the mark.

There, Chapin told the group, “I was in Modesto that night, standing right there. The mark was real. Everyone in the stadium knew it was real. I absolutely accepted it.”

Hersh and the Records Committee might have felt no qualms about stonewalling a former 60s radical, but Chaplin couldn’t be dismissed. He was a member of three Halls of Fame (USATF, Washington State, Pasadena City College), had been International Coach of the Year in 1978 and head coach of the U.S. men’s track team at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney.

With Chaplin’s testimony, the Executive Committee reversed the Records Committee, officially recognizing Phillip Kent Shinnick of Spokane, WA., as a one-time American record holder. USATF CEO Craig Masback agreed to write a letter to the IAAF urging that it recognize Shinnick’s 27-4 as a one-time world mark. Chaplin delivered the news to Shinnick in a telephone call Dec. 6 and The Associated Press reported the story Dec. 10.

“The Men’s Executive Committee overturned it because John Chaplin was standing by the takeoff board when I did it, so it became an American record,” Shinnick wrote in a message he posted on the National Masters News web site. “Hersh was so mad that he stormed into the meeting several times and Chaplin told him if he didn’t exit because of his personal animosity he would head butt him and drag him out by his heels. For me, it was just finding peace of mind.”

Chaplin recused Hersh from dealing with Shinnick’s record at the IAAF to give Shinnick a chance for ratification. According to its Council members, including Sebastian Coe and others, Hersh, subsequently an IAAF vice-president, became the force against support for Shinnick’s record. Shinnick’s supporters are still waiting for a change in IAAF leadership to put forth the record to override Hersh. Council members assert that this is a political issue.

—————————————-

The obvious question is why? Why did the USATF stonewall Shinnick after 40 years? To answer that, you have to go back to May 25, 1963. Cordner Nelson, co-founder Track & Field News, the self-proclaimed “Bible” of the sport, sat well up in the stands as Shinnick went 27-4. From that perspective, Cordner arbitrarily reported that Shinnick’s mark should be disallowed.

Track officials simply “bought” Cordner’s guess on wind conditions. Further, there is no evidence Track & Field News interviewed Shinnick, the meet director, the wind gauge official, or any other eyewitness to the jump. But once its version of the event got “out there,” Track & Field News would not have wanted to admit it made a mistake. So it stuck by its story and U.S. track officials had no mind to take on the “The Bible.”

Richard Hymans, a prominent World Record consultant to the IAAF, was asked why he didn’t pay attention to Sports Illustrated’s reporting, or the reporting of Seattle and San Francisco newspapers, all in agreement that Shinnick’s jump had not been influenced by the wind, and was therefore valid. Hymans replied that he didn’t read those publications and only subscribed to Track and Field News.

During the Greensboro hearing, Track & Field News continued to argue against Shinnick. Even after the USATF accepted his jump as a one-time American mark, Track & Field News refused to report that fact.

Tom Moore, meet director at Modesto, also provided a startling reason for the stonewalling. In 1994, Shinnick and Guy Benjamin, a former Stanford quarterback and a member of Athletes United For Peace, founded by Shinnick, Jim Ryan, Bob Beamon, Dave Meggyesey and others in the early 1980s, visited Moore to take his statement on the events of May 25, 1963.

Benjamin’s affidavit stated, “Tom Moore talked about tying the world record in the high hurdles at the University of California Stadium in the 1940s when there was no wind gauge. He got the record based upon Brutus Hamilton’s reputation and affidavit, as a meet director, attesting to no wind.

“We conjectured what Tom Moore’s life would be like if that hadn’t happened, and he attributed his position at the California Relays to his world record. He was very grateful. We asked Dr. Moore, why if all the officials came to him urging the approval of Shinnick’s record, he didn’t do what Brutus Hamilton did for him?

“He said that if he did so Ollan Cassell, the AAU Director, would take away the sanction of the California Relays and his position, which he cherished. Cassell’s blacklisting of Dr. Shinnick was well known. He (Moore) told us he would write Dr. Shinnick a letter telling the truth of what had happened at Modesto to clear his conscience. His letter is Appendix 4 of the (records application) Submission dated 8/4/94.

“Dr. Moore mentioned other testimonies that went to Bob Hersh at the national office. I am also aware of Bob Hersh’s similarly prejudiced position against Dr. Shinnick by the fact that he told the national press that there was no evidence that Dr. Shinnick’s jump was a legal jump when he knew such evidence existed from other affidavits from officials at Modesto sent to him, which (he) burned in a fire in his apartment.”

It’s difficult to determine now why Cassell and Hersh harbored such deep animosity. But as Benjamin, co-Pac-8 Player of the Year in 1977 with Washington’s Warren Moon, suggested, “it was politics.”

On May 25, 1963, Shinnick caught Track & Field News, the “Bible of the Sport,” unaware and unprepared – hardly a ringing endorsement for a “Bible” considering Shinnick’s two legal jumps over 25 feet in the previous weeks, his 26-foot scratch at Berkeley earlier that day, and his 26-10 scratch immediately before his 27-4.

Plus, Shinnick (and Sternberg) had been invited to Modesto, which hosted only the world’s greatest athletes. It can reasonably be argued that, as a “Bible,” Track & Field News should have had a grasp on each of the Modesto competitors, but didn’t. Through no fault of his own, Shinnick exposed Track & Field News as somewhat less than “biblical.”

Shinnick also probably had not endeared himself to some of the more conservative elements in the track establishment. He had received an advanced degree from Cal-Berkeley, ground zero for campus radicals in the 60s. Shinnick counted among his friends Jack and Micki Scott, two individuals not only outside, but largely opposed to the mainstream of American sport. He called John Carlos, who had embarrassed some USA officials at the 1968 Olympics, a friend. Then there was that Patty Hearst business and Shinnick’s refusal to genuflect before the FBI.

Shinnick contributed articles to Sovietsky Sport and New China at the height of the Cold War, once publishing a piece (1977) in New China titled Are Superstars Really Necessary? Shinnick, who also wrote for The New York Times as a guest editorialist on sports and politics, did not support the U.S. boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, lobbied to get China into the Olympic movement at a time when China was on the outs, and preached for world peace and human rights.

When nuclear weapons proliferation heightened between the U.S. and USSR, Shinnick organized peace delegations to travel behind the iron curtain to study how the Soviets organized competitions. When it was not politically correct to do so, he founded the Moscow Peace Marathon.

Shinnick might have become a Park Avenue doctor, but he practiced alternative medicine. Finally, USATF probably thought Shinnick asked too many questions, demanded too many answers, and wouldn’t go away 40 years.

After he re-claimed the American record, Shinnick said, “I was unhappy all the time, and now I’ve learned to be happy. All of this has taught me to believe in my own senses.”

USA Track & Field submitted Shinnick’s American record 27-4 to the IAAF for world record ratification. That was a decade ago and it’s now been 50 years since Modesto. Dr. Phil is still waiting for final validation and vindication.

———————————————————–

Also See:

Huskies Vault Legend Brian Sternberg (1943-13)

Wayback Machine: A Memorable Day, May 25, 1963

Wayback Machine: Sternberg Coped With Hope

————————————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

nz.linkedin.com/pub/grant-birkinshaw/17/454/807/

6 Comments

Wow! Amazing person, Phil Shinnick! The select group of us affected by Ollan Cassell’s politically motivated decisions emotionally connect with PS’s invisibility. I myself was banned from international track competition when I,as 1990 National Champion, collected a Versaclimber and $300 at U.S. National Amateur Triathlon Championships. Although I raced amateur level to merely cross-train and protect my track eligibility, OC refused to allow deposit of that $ into my TAC Trust Bank Account, his decision immediately banning me from international track races, future U.S. Track Teams and the Olympics. Without this visibility, Track Sponsorship worth thousands dried up overnight. By encountering that slammed door, I, by default, joined my twin sister on the Professional Triathlon Circuit. As a fellow former World Record Setting ghost, I stand and applaud every one of your global achievements, Phil Shinnick. Until today, I knew none of your story. I am now a full-fledged fan…

Joan Hansen

1984 Olympian

T & F 3000 m.

Joan: Thanks so much for your comments. Dr. Phil has always been — and continues to be — a victim of politics at the highest level of the sport. He has been criticized for refusing to let this issue go, but I think his tenacity is part of his DNA as a world-class athlete. I found him to be a rather remarkable — maybe even unbelievable — individual for all the right reasons. I would appreciate it if you could share Phil’s story with some of the Olympians from your era. Finally, it doesn’t surprise me that you got shafted. I learned a lot about Olan Cassell during the research for this article.

Joan: Thank you so much for adding your comments. Dr. Phil is a remarkable individual.

I first met Phil at Livingston College as one of his students. We became friends, training partners, and I had the pleasure of living in Phil’s house and having him as a continual source of track and field knowledge. I learned more about training in one workout with Phil than I learned in a semester in grad school studying exercise physiology. I’ve just retired from coaching and in thirty years of sharing knowledge with my athletes I have to say that everyone of those athletes heard about Phil and what he taught me. He was a world class competitor, a sponge for knowledge, and a generous mentor.

I’ve long known this story and lived through parts of it with him. He deserves more than recognition for his world record – he’s owed the record and an apology.

Vinny Finneran

Thank you for sharing that.

Thanks so much for sharing that.