By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

A Seattle tradition now in its 79th year, the MTR Western Star of the Year, which begins at 5:30 p.m. Wednesday at Benaroya Hall and is hosted by ESPN’s Kenny Mayne, began with a simple question posed by Royal Brougham in his popular Seattle Post-Intelligencer column, “The Morning After,” published Feb. 23, 1936.

“Who,” Brougham queried his readers, “was the Man of the Year in local athletics in the past 12-month period?”

Employed at the P-I since 1916, and a hunt-and-peck typist who banged on a Remington typewriter older than he was, Brougham listed a dozen sports personalities from 1935 that, in his view, merited consideration, and asked readers to provide feedback.

One week after his initial query, Brougham began running a coupon in the newspaper labeled “Morning After Man of the Year Contest” to further encourage voting. As an inducement, Brougham offered $10 for the best essay of 75 words or less nominating the winning candidate.

Over the next month, Brougham issued frequent updates on the status of the voting. For the first few days, University of Washington basketball coach Clarence “Hec” Edmundson topped the balloting, only to be overtaken by Frank Foyston, head coach of the Seattle Seahawks hockey team and captain of the 1917 Stanley Cup champion Seattle Metropolitans.

Three weeks into Brougham’s contest, swimming coach Ray Daughters, famous for having coached Seattle’s Helene Madison to three gold medals at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics and for having developed national champion Jack Medica, became the voting leader.

Finally, on March 10, 1936, Brougham assembled a dozen of his cronies and sat them down for a 75-cent lunch at two tables opposite each other at the Washington Athletic Club. The group’s mission: sort through a list of 12 nominees — none of them in attendance — vet the candidacies, and declare a winner.

Brougham already put forth the credentials of the candidates in that morning’s P-I. This is what he wrote:

“Kewpie Barrett (Seattle Indians) is quite probably the outstanding Seattle ballplayer in fifteen years. Tom Bolles (UW rowing) won his third national title at Poughkeepsie, while Scotty Campbell is Northwest amateur golf champion and a leading contender for the Walker Cup team. Ray Daughters coached his team to national swimming titles, while Hec Edmundson’s Huskies are in the midst of an astounding season.

“Frank Foyston brought his hockey team from last to first place. Jack Medica continued his brilliant record-breaking feats, while Bobby Morris brought fame to the Northwest by being chosen to referee the most important games of the West. Hank Prusoff made a fine showing in national tennis tourneys, Hannes Schroll was the skiing sensation who won the Silver Skis Race on Mount Rainier, Bill Smith (UW) won All-America football honors, while Freddie Steele fought himself into the No. 1 ranking among U.S. middleweights.”

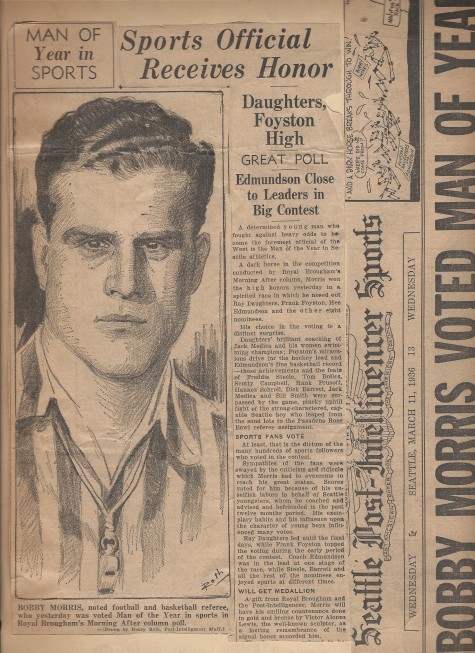

In the following day’s Post-Intelligencer (March 11), a large, bold headline stated: “Bobby Morris Voted Man of Year.”

That Morris won surprised Brougham, Brougham’s readers and even the winner, Bobby Morris. An incredulous Morris even told a reporter, “There is probably some mistake here. I voted for Hec Edmundson and he should have won the honor.”

“Let’s you and I be frank about it — the dictum of the voters was surprising,” opined Brougham in his “Morning After” column. “And, yet, why not Bobby Morris? You ask, what has he accomplished?

“Listen up! In one year the square-chinned little fellow licked the entire state of California. Because he was a product of the sand lots and never went to college, Morris was bitterly assailed by the football populace from Berkeley to the flower-bedecked stadium at Pasadena.

“By sheer courage and ability, he merited his selection as chief official of the titular Big Game at Palo Alto (Cal vs. Stanford) and later as referee-in-chief at the greatest gridiron spectacle in America — the Rose Bowl Classic.

“But officiating at football, basketball and baseball games is only one reason for Morris’ amazing popularity. Thousands of Seattle youngsters have been coached, advised and befriended by the stocky young man with curly hair.

“He fathered the American Legion baseball teams last summer; he gave freely of his services in coaching Seattle’s Japanese teams; he gave valuable aid to younger and less-experienced referees. His services were in constant demand at high schools and luncheon clubs. While no softie in any sense of the word, he is a man of fine character, excellent habits, and the kind of leader you’d like your son to associate with.”

The Post-Intelligencer carried a separate editorial on Morris’s victory. It stated, in part, “Sympathies of the fans were swayed by the criticism and ridicule which Morris had to overcome to reach his great status. Scores voted for him because of his unselfish labors in behalf of Seattle youngsters, whom he coached and advised and befriended in the past 12 months.

“His exemplary habits and his influence upon the character of young boys influenced many votes. Ray Daughters led until the final days, while Frank Foyston topped the voting during the early period of the contest. Coach Edmundson was in the lead at one stage of the race while Freddie Steele, Kewpie Dick Barrett and the rest of the nominees enjoyed spurts at different times.”

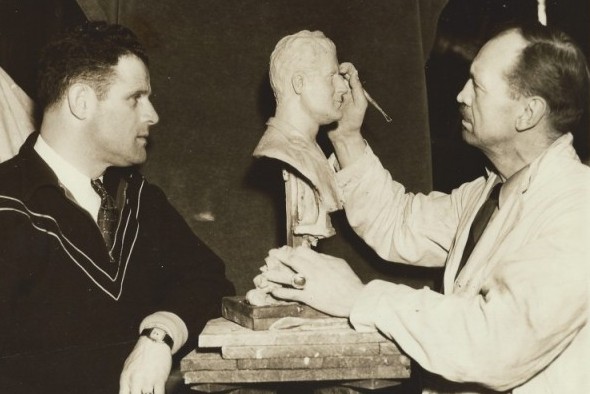

Morris received a gift from Brougham and the P-I: His smiling countenance done in gold and bronze by Victory Alonzo Lewis, a well-known sculptor.

Among the nominees who didn’t claim the first Man of the Year award, two, Barrett in 1940 and Edmundson in 1943, became winners in subsequent years. But Bobby Morris was the first.

Born Oct. 17, 1897 in Glasgow, KY., to Edward and Julia Morris, Robert Alexander Morris arrived in Seattle in 1900, the family migrating West at the urging of Julia’s sister, who had already relocated. Edward Morris went into real estate – he died tragically in a shotgun accident when Bobby was 12 — and Bobby attended Columbia and Lowell elementary schools and Broadway High, where, from 1913 through 1916, he starred in football, basketball, baseball and track, and was part of Broadway’s 1914 City Championship football team, coached by the legendary Elmer “Gloomy Gus” Henderson.

After high school, Morris couldn’t attend college because the family lacked the money, so he worked as a paymaster in the Seattle shipyards, his first experience with ledgers and numbers, quitting to enlist in the U.S. Army in 1918. Upon his discharge, Morris began playing semipro baseball, notably as player-manager of the “Black Pitts” team in the Butte Mines League, a feeder for the Pacific Coast League.

Returning to Seattle, Morris became a Seattle Parks Dept. playfield instructor, continued his semipro baseball career (The Times named Morris to its “1920-30 Seattle Semipro All-Star” team), and also refereed basketball in the old Seattle Church League and basketball and football in Seattle public school contests, learning the art of whistle-toting from the West Coast’s top official of the time, George Varnell, later sports editor of The Seattle Times.

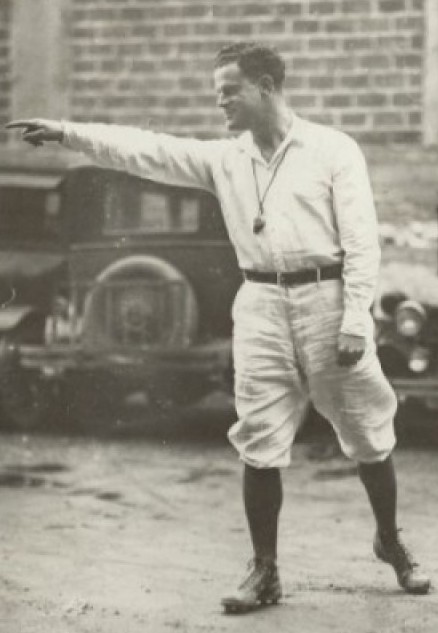

Morris learned officiating so well that in 1919, before he was old enough to vote, he went to work for the Pacific Coast Conference, forerunner of the Pac-12. He worked his first conference game, Washington vs. Whitman, Oct. 9, 1920 at Denny Field.

Five years later, at age 26, Morris drew his first Rose Bowl assignment. That year, Knute Rockne brought the Fighting Irish and their Four Horsemen to Pasadena to play Pop Warner’s Stanford team.

Notre Dame, in its first-ever bowl game (and only Rose Bowl appearance), won 27-10 and Morris told The Times’ Vince O’Keefe many years later, “That 1924 Notre Dame team was the best I ever saw. But the best player I saw in all my years of officiating, including the Four Horsemen, was George Wilson of Washington. Bar none.”

Morris, who also officiated the 1935, 1936 (Washington vs. Pittsburgh) and 1939 Rose Bowls, worked PCC football and basketball games through 1940 and had a reputation as being scrupulously fair. In fact, only once did a team accuse him of wrongdoing.

In 1936, Morris worked a Washington State-Stanford football game and the Cougars won. Some of the Stanford players accused Morris of aiding the WSU cause by tipping Stanford’s formations to quarterback Ed Goddard of the Cougars, and for specifically allowing a touchdown that Washington State didn’t deserve.

Morris sued Stanford, alleging slander. At the time, Morris worked for the A.C. Spalding Shop and the sporting goods company asked him to drop the suit in the interest of business harmony. When Morris refused, Spalding let him go.

But it just so happened that an amateur photographer took a picture of the play in question. It showed clearly that Morris made the correct call. Stanford moved quickly and settled with Morris out of court, vindicating him.

“He was the best, especially in basketball when only one official worked a game,” wrote Varnell. “He didn’t care whether it was the home crowd or not, whether it was Washington, Oregon or Podunk – he called ’em and that was it. They stayed called.”

Between 1919-40, Morris refereed thousands of basketball games on the prep and collegiate levels, ultimately rising to “Commissioner of Officials,” a job in which he was tasked with hiring and instructing all referees assigned to work PCC Northern Division games.

No one worked more often than Morris. In 1923, three referees worked the first state high school basketball Tournament, created by Edmundson and UW football/baseball coach Tubby Graves. Morris called 18 of the 26 games in a three-day span. Another time, he worked 100 basketball games in 65 days.

“In those days, I worked alone,” Morris told Tom Hopkins of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in 1966. “Those 100 games in 65 days included single games, doubleheaders and tournaments. I traveled 14,000 miles by car and train in those 65 days.”

“He was the best basketball official I ever saw,” former Hawaii football coach Phil Sarboe told Hopkins. “And what a memory. Before a game he would study the lineups and when he called a foul he didn’t designate the culprit by number, but called him by name.”

Morris was so well respected for his work as an official that the Post-Intelligencer hired him in 1933 to produce a weekly commentary for the paper on West Coast football and to select All-State and All-Coast teams at the end of the season. Morris was also in constant demand as a public speaker. He delivered more than 150 speeches per year to service clubs and various associations and was sought after to serve on the boards of numerous charities, including the March of Dimes and American Red Cross.

Still, as Brougham noted, his selection as the first Man of the Year came as a surprise. Back in those days – and up to 1974 – the winner was chosen by vote of a tribunal of citizens, not by a public vote of sports fans, as is the case today.

The old tribunal was “something else,” as former Seattle columnist Emmett Watson once described it. As early as October each fall, lobbying began to get certain people on this tribunal. Anyone running for anything, including dog catcher, tried to be a member of the tribunal. And as the day approached for the awards luncheon, the tribunal itself was lobbied.

Citizens, prominent or otherwise, who were picked for the tribunal found themselves members of a jury that had no court rules. Friends and supporters of “sports star” candidates laid heavy pressure on the tribunal. Many, according to Watson, received 50 or more phone calls on behalf of a single candidate.

As the “Man of the Year” program evolved, it moved out of the Washington Athletic Club and into the larger downtown hotels, went from a luncheon to a dinner and finally a banquet. For several years, local TV aired the announcement of the winner live.

“It became one part Gong Show, one part Ed Sullivan, a large dose of Lawrence Welk, with a little old-time vaudeville thrown in,” Watson once wrote.

“Royal Brougham, bless his heart, was a man of warmth and imagination, but he wasn’t strong on details. Thus the show had some spectacular gaffes, including one night when, while introducing the candidates, Brougham dropped a page out of his script. This was on television, mind you, and at least half the candidates never got introduced. That night, the P-I switchboard lit up like a pinball game with irate, indignant fans yowling that their favorite had been slighted.”

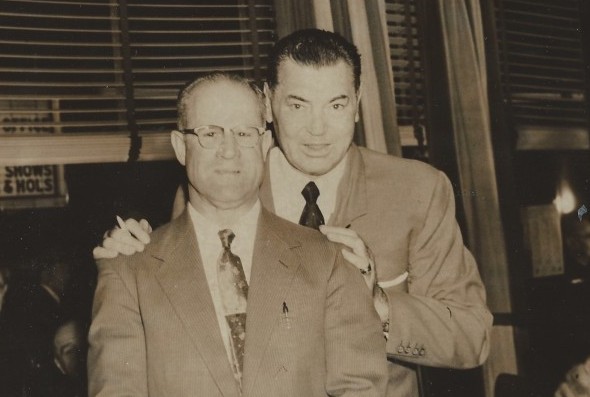

Brougham had a particular knack for attracting celebrity speakers. He cajoled an array to show up over the years, including Jack Dempsey (1951), Tom Harmon (1953), Babe Didrickson Zaharias (1954), Jesse Owens (1955) Stan Musial (1957), Red Grange (1959), Otto Graham (1958), Johnny Unitas (1963), Willie Mays (1964), Duffy Daugherty (1966) and Al Kaline (1969).

In the years before Seattle became a pro sports town (1935-69), Man of the Year nominees included candidates who probably would not find their way on the ballot today. Steve Morrissey, president of the state Sportsmen’s Council, won in 1946. Trapshooter Arnold Riegger won in 1954. Nominees included a badminton player (Mrs. Del Barkoff, 1937), an archer (Kore Duryee, 1943), a squash player (Ted Clarke, 1948), and even an animal, Ace “The Wonder Dog,” in 1952.

So, as Brougham said, Bobby Morris had credentials as good as anyone when he became the first Man of the Year.

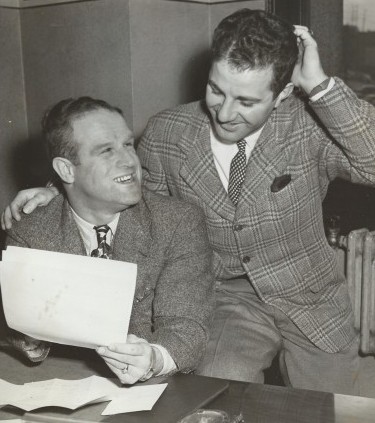

A year after winning the award (Oct. 1, 1937), Morris was appointed Chief Deputy Auditor for King County. For the next three years he juggled that job with refereeing assignments and continued to play a role in Seattle sports beyond the playing field. In 1938, for example, together with UW football coach Jimmy Phelan, Morris helped convince Edo Vanni to forgo a football scholarship and sign with Emil Sick’s Seattle Rainiers. Morris negotiated the contract.

For a number of years, Morris worked as chief judge at Longacres Race Course. He served a term as president of the Seattle chapter of the National Football Foundation and also emceed the annual “Moaners Club Banquet,” organized by Morris and two of his poker-paying friends, UW baseball coach Tubby Graves and restaurateur Les Brainard. Purpose of the banquet: to gather sports-minded guests – Torchy Torrance, UW football coach John Cherberg and local baseball legend Ten Million were regular guests – for an evening of good-natured ribbing.

A strained leg muscle Morris suffered while working the 1939 Illinois-USC football game refused to yield to treatment and in the early fall of 1940 he informed the PCC he would be unable to carry out any further officiating assignments.

On April 1, 1941, Morris was appointed to fill the unexpired term of King County Auditor Earl Millikin, who had been elected mayor. Morris ran as an incumbent in 1942 and was elected to the post – his primary task was ensuring the integrity of county elections — every four years until he retired due to illness in 1969.

“Bobby Morris, who at one time was one of the country’s outstanding basketball and football officials, was known for his integrity, courage and absolute fairness,” The West Seattle Herald wrote in 1946. “He has carried those attributes into the office of county auditor and is recognized as one of our most respected and best-liked county officials.”

When Morris stepped down, Ross Cunningham published this tribute in The Times: Robert A. Morris, now stepping away after 28 years as King County Auditor, has left his mark on the public scene in a variety of ways. First, years ago, he was a stern, but impeccably impartial referee in collegiate and semipro sports. The name Bobby Morris became a hallmark of good sportsmanship and clean conduct on the gridiron and basketball courts. He blew a sharp whistle when the occasion demanded.

“As county auditor, he looked after official records of many kinds and never performed hanky panky with those books. No one ever questioned the integrity of the auditor’s office. Morris, together with his election supervisor, Ed Logan, was a guardian of elections honestly conducted and honestly counted. For that, Morris deserves tribute.”

One year after Morris’ death — April 18, 1970 — the City of Seattle renamed the Broadway Playfield, where he worked for many years, the “Bobby Morris Playfield” (1635 11th Ave.).

“Bobby was known for his work at Broadway Playfield when it was originally known as Lincoln Park,” wrote O’Keefe. “In those years, it was a hangout for bully boys. Morris, a stocky and rugged individual who took no sass from anybody, soon straightened out the bullies, and it wasn’t long before Broadway was a model for fair play and gentlemanly decorum.”

Athlete, referee and public servant, Morris left a wife, Dorothy, and a daughter Marilyn, who still lives in the Seattle area.

“He was just such a nice person, very funny, entertaining and very honest,” said Marilyn. He loved people.”

And, rare for a ref, people loved him back.

————————————————————

The 79th Annual MTR Western Sports Star of the Year event Wednesday will honor Washington State’s biggest athletes, coaches, executives, media figures, philanthropists and stories of 2013.

Tickets to the event at Benaroya Hall in downtown Seattle are still available and can be purchased through the Benaroya Hall Box Office, at benaroyahall.com, or by calling (206) 215-4747. Premium tickets allow VIP access to the 5:30 p.m. reception attended by some of this year’s nominees and a silent auction and 7:30 p.m. show for $100. Tickets for just the 7:30 p.m. show are $25.

To learn more about the MTR Western Sports Star of the Year and this year’s nominees, visit www.sportsstaroftheyear.org.

——————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David?s ? Wayback Machine Archive.? David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Excellent piece. Today’s game, in all sports, doesn’t allow for such respect be given to sport referees. Many times they can be viewed as the villain. (Super Bowl XL anyone?).