By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Established in Canton, OH., in 1963, the Pro Football Hall of Fame includes 287 individuals who played, coached or otherwise developed the NFL into the colossus that it is today. With the addition of former Seahawks tackle Walter Jones (1997-2009) Saturday in the Class of 2014, those with significant ties to the state of Washington number 11.

For accounting purposes, we don’t include the likes of former Denver Broncos quarterback John Elway, born in Port Angeles in 1960, due to a minimal association with the state. Nor do we include Hall of Famers such as Carl Eller, Franco Harris, Jerry Rice and John Randle, who sipped cups of coffee with the Seahawks near the end of their careers.

Although Hugh McElehnny, a California native, played only 28 games for the Washington Huskies (1949-51), he lived and worked in Washington for many years following his career before ill health forced him into retirement in the dry climate of Henderson, NV.

Warren Moon also came to Washington from California and, as with McElhenny, spent three years with the Huskies (1975-77). But Moon played two subsequent seasons with the Seahawks (1997-98) and has remained active with the franchise as a broadcaster.

Under our criteria, the following are Pro Football Hall of Famers with significant ties to the state, starting by year of induction, with Mel Hein, who played under Babe Hollingbery at Washington State in the late 1920s before embarking on a career that made him a New York Giants legend.

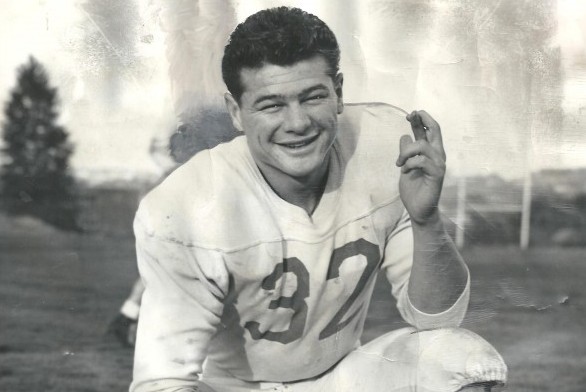

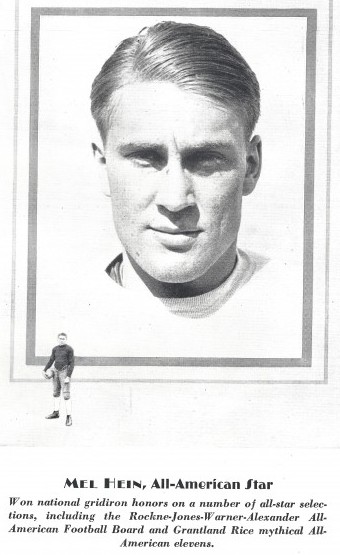

MEL HEIN / Class of 1963

Born Aug. 22, 1909 in Redding, CA., 6-foot-2, 225-pound Melvin Jack Hein initially expressed interest in becoming a rower, but gravitated to football and basketball when he discovered how good he was at those sports.

WSU coach Babe Hollingbery recruited Hein out of Burlington-Edison High after he attracted Hollingbery’s attention as a center and defensive lineman. As a senior, Hein earned the Skagit County Football MVP award, and then played all three interior line positions at Washington State from 1928 through 1930. During Hein’s tenure, WSU went 26-6, winning 15 by shutout.

Also a center on Jack Friel’s basketball team and winner of the javelin at the 1931 Drake Relays (199 feet, 9 inches), Hein made Grantland Rice’s All-America team and first-team All Coast after playing virtually every minute of every game.

Since the NFL did not have a draft in those days, Hein took it upon himself to make his own way in the pros, writing letters to three teams, offering his services. He did not hear back from the Portsmouth Spartans (forerunner of the Detroit Lions, who employed former WSU teammate Elmer Schwartz) but did hear from the Providence Steamroller, which sent him a contract offering $125 per game.

Hein signed it and mailed it back. The next evening, Hein ran into Ray Flaherty, a New York Giants receiver (1923-25), who played at Washington State and Gonzaga, at a Cougars basketball game in Pullman. Flaherty told Hein that the Giants had just mailed him a contract offering $150 per game.

Hein hastily wired the Providence, RI., postmaster, described his letter to the Steamroller, and asked that the postmaster return it. For whatever reason, the postmaster violated regulations and sent the contract back to Hein, who destroyed it. With that, the Giants got one of the greatest players in NFL history.

Hein got his chance to play when both of New York’s centers suffered injuries, reducing the pair to a Wally Pipp fate. Hein made second-team All-Pro his first two seasons and was widely considered the best player in the league every year after that.

“Even in his final campaign at 36, Mel was still playing every game from the first kickoff to the final gun,” noted the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “Mel combined great stamina, a cool head, mental alertness and simply superior ability to become an exceptional star.

“He was named first-team All-NFL center eight straight years from 1933 through 1940. He also earned second-team All-NFL five other times. In 1938, he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player, a rare honor for a center (no interior lineman has won it since). He was the team captain for 10 seasons.”

Hein entered the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954 and became a charter member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963. In 1969, Hein was named the center on the NFL’s 50th Anniversary Team, and that same year was voted one of the 11 all-time best professional and collegiate football players in a vote conducted in conjunction with professional football’s centennial. In 1994, Hein made the NFL’s 75th Anniversary Team.

The Washington State Board of Regents honored Hein May 14, 1983, with its Distinguished Alumnus Award. By the time WSU feted Hein, he retired to San Clemente, CA., where he died Jan. 31, 1992 of stomach cancer at 82.

GLEN “TURK” EDWARDS / Class of 1969

After Albert Glen Edwards, born Sept. 28, 1907, in Mold, WA., left WSU in 1931, five years before the first NFL draft, he received offers from three franchises, the Boston Braves, New York Giants, and Portsmouth Spartans. Edwards could have joined Hein’s Giants but chose the highest bid –- $1,500 for 10 games — from the Braves, a team that would later become the Boston Redskins and then move to Washington D.C. in 1937.

Edwards, who earned All-NFL honors every year of his career (first-team All-NFL in 1932, 1933, 1936, 1937) except the last one, didn’t spend nearly as much time with the Braves/Redskins (nine seasons) as Hein did with the Giants, but, like Hein, played every minute of every game.

For most of his tenure with the Redskins, Edwards played for Spokane native Ray Flaherty, who became Boston’s coach in 1936. Edwards also served as an assistant under Flaherty (1941-42).

Oddly, Edwards’ career came to an end due to an injury that did not even occur during a game. Prior to a meeting with the Giants in 1940, Edwards, the Redskins’ captain, went to the center of the field for the coin-toss ceremony. Representing New York: Edwards’ former Washington State teammate Hein.

After shaking hands with Hein, Edwards attempted to pivot around to head back to his sideline. However, his cleats caught in the grass and his knee gave way, ending his season and ultimately his career.

Edwards continued with the Redskins as an assistant coach from 1941 to 1945 and as head coach from 1946 to 1948, leading a team quarterbacked by Sammy Baugh. Then, after 17 seasons in the club’s employ, Edwards retired and returned to the Pacific Northwest.

For a number of years, Edwards sold sporting goods out of a store in Seattle’s University District. In 1961, he relocated to Kelso, where he spent 12 years in the Cowlitz County assessor’s office.

Edwards entered nearly as many halls of fame as Hein, including the Inland Empire (1966), State of Washington (1968), Pro Football (1969) and College Football (1975). He died in Kirkland Jan. 12, 1973 after a long illness. He was 65.

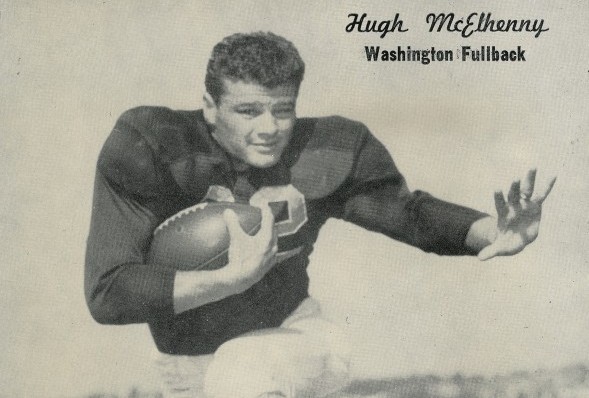

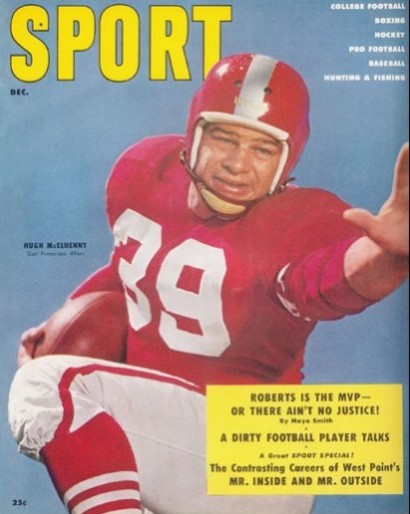

HUGH MCELHENNY / Class of 1970

After three record-breaking seasons (1949-51) at Washington, during which he set every school rushing record, McElhenny joined the San Francisco 49ers as their first-round pick in the 1952 NFL draft. McElhenny scored a 40-yard touchdown on his first pro play and entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

He became the first ex-Husky to reach Canton and did so after winning the 1952 Rookie of the Year award, earning six Pro Bowl invitations, twice making first-team All-Pro and the NFL’s All-Decade Team for the 1950s.

Born Dec. 31, 1928 in Los Angeles, McElhenny graduated from L.A.’s Washington Prep High and enrolled at Compton Junior College, where one of his teammates was Joe Perry, who became a 1969 inductee in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The Huskies won a “bidding war” for McElhenny in 1949, when he began his life-long relationship with quarterback Don Heinrich, and in 1950 McElhenny came into his own, starting off the season with a 177-yard day against Kansas State. McElhenny finished the season with a record that still stands, a 296-yard, 5-TD performance against Washington State.

After McElhenny finished rewriting the Pacific Coast Conference record book in 1951 – he became the first player in league history to score on a 90-yard kickoff return, a 90-yard run and a 90-yard punt return – he began tearing through NFL defenses as if he’d hardly moved up in class.

As a rookie, he recorded the season’s longest run from scrimmage (89 yards), the longest punt return (94) and set a record by averaging 7.0 yards per carry.

“Considered the greatest ‘thrill runner’ of his day, McElhenny ran with a tremendously long stride and high knee action,” wrote an archivist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “His breakaway speed and unique ability to change direction at will left defenders dazed and confused. He was an artist whose electrifying moves left opponents and observers spellbound and sportswriters groping for new superlatives to describe his exciting style of play.”

In 1961, after nine seasons and five Pro Bowl appearances (1958 MVP), McElhenny joined the Minnesota Vikings and delivered his finest season with 1,069 combined yards that sent him to the Pro Bowl for the sixth time.

When he retired following the 1964 season, which he spent with the New York Giants, McElhenny had become one of three players with 11,000 all-purpose yards. On rushing, receiving, kickoff returns, punt returns, and fumble returns, he totaled 11,375 yards — more than six miles.

McElhenny entered the College Football Hall of Fame in 1981 and was voted to the NFL’s 50th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1969. The 49ers profited most from McElhenny’s impact.

“When Hugh joined the 49ers in 1952,” Lou Spadia, the team’s general manager, recalled in the mid-1950s, “it was questionable whether our franchise could survive. McElhenny removed all doubts. That’s why we call him our franchise-saver.”

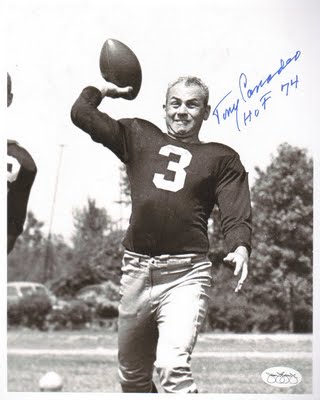

TONY CANADEO / Class of 1974)

As with a number of small, underfunded colleges, Gonzaga University ended its football program in 1941, just before the U.S. entry into World War II. Despite its tiny enrollment, which ranged from 2,000-3,000 students from the 1920s until the war years, Gonzaga produced two members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Canadeo and Ray Flaherty.

Canadeo, 5-foot-11 and 190 pounds, made Little All-America in 1939, when he earned his nickname, “The Gray Ghost of Gonzaga,” because he was prematurely gray. He joined the Green Bay Packers as a ninth-round draft choice in 1941 and spent his entire career with the club except for a stint in the Army during World War II.

Canadeo came out of Chicago (born May 5, 1919). Two years into his pro career (1943), he made first-team All-Pro as a quarterback and, after his return from the Army in 1946, served Green Bay as its primary ball carrier, becoming the third player in history to rush for more than 1,000 yards in a season.

Canadeo did more than run and throw. During his career, he also made 11 interceptions and served as Green Bay’s punter. Canadeo had another 1,000-yard season in 1949 (1,052), when he made first-team All-Pro for the second time.

Canadeo’s playing career ended in 1952, but he maintained a lifelong association with the Packers. He made his home in Green Bay and worked as a broadcaster with the club and on the team’s executive committee.

A member of the All-NFL Team of the 1940s, Canadeo made a major contribution to Packers history in 1959 when he was instrumental in convincing New York Giants assistant coach Vince Lombardi to take over as head coach of the Packers.

Canadeo, who played in 116 NFL games, earned induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his fourth year of eligibility. He died Nov. 29, 2003 in Green Bay at 84.

RAY FLAHERTY / Class of 1976

Born Sept. 1, 1903 in Spokane and a graduate of Gonzaga University, Flaherty had an unremarkable career as a professional player, spending time as a receiver with the Los Angeles Wildcats of the American Football League in 1926, the NFL’s New York Yankees in 1927-28 and New York Giants from 1928-35.

Flaherty took 1930 off in order to return to Gonzaga and coach his alma mater, and received his first pro head coaching position in 1936, with the Boston Redskins, a year after his retirement as a player.

Flaherty coached the Redskins from 1936 to 1942, winning four division titles (1936, 1937, 1940, 1942) with the game’s greatest quarterback, Sammy Baugh, and NFL championships in 1937 and 1942.

Flaherty served in the Navy during World War II and, upon his return, became head coach of the New York Yankees of the All-America Football Conference. After three years with the Yankees (1946-48), he coached one year with the AAFC’s Chicago Hornets.

Flaherty invented the screen pass in 1937 and was instrumental in convincing Mel Hein to sign with the New York Giants. He entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. Flaherty died July 19, 1994, at 90, in Coeur d’Alene, ID.

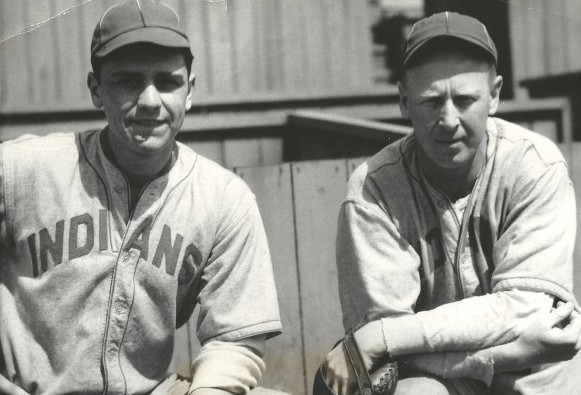

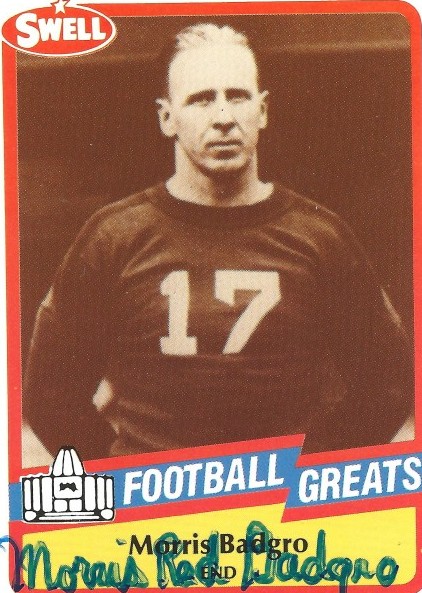

RED BADGRO / Class of 1981

Badgro scored the first touchdown in the NFL’s first championship game (1933), is the only man to play for the football versions of the New York Giants, New York Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers, is the only man to block for Red Grange and coach Hugh McElhenny, and is the oldest individual elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Born Dec. 1, 1902 in Orillia, WA., a long-gone community southwest of Renton in the Green River Valley, Morris Hiram Badgro starred as an all-everything athlete (football, basketball, baseball) at Kent High School in the early 1920s (graduated 1921) and then spurned the University of Washington and enrolled at USC on a basketball scholarship.

He lettered four years in football (All-Coast three times), basketball (captained the 1927 varsity) and baseball (PCC Southern Division All-Star), found time to work as an extra in movies with football teammate and future actor John Wayne, and then began his professional odyssey in 1927 with Red Grange’s New York Yankees of the All-America Football Conference. The 6-foot, 190-pound Badgro’s primary job: Block for the Galloping Ghost.

When the league collapsed in financial ruin after Badgro’s second season, he decided to give baseball a whirl and became a minor league outfielder in the St. Louis Browns system, first with Class C Muskogee of the Western Association (hit .394 in 37 games) and then with Class A Tulsa of the Western League (hit .334 in 92 games).

A year later (1929), Badgro joined the Browns. He battled Beauty McGowan and Tedd Gullic for playing time and didn’t have a noteworthy career with the club, batting .257 with 211 hits, two home runs and 45 RBIs in 143 games, but he had a four-hit game at the expense of future Hall of Famer Waite Hoyt Aug. 22, 1929 at Sportsman’s Park, and a pair of three-hit games against Hall of Famer Rick Ferrell.

Late in 1930, when the Browns demoted Badgro to Houston of the Texas League, he received a call from New York Giants coach Steve Owen, who offered Badgro $150 per game, the going rate, and his major league career ended — but not his minor league career, or even his basketball career.

For the next six years, Badgro starred as a two-way end on a Giants team that included future Hall of Famer Hein. He was named All-NFL, either first or second team, in 1930, 1931, 1933 and 1934. During those years, Badgro played minor league baseball and amateur basketball in Seattle’s Commercial League.

Badgro had his best year in the NFL in 1934 when he tied for the league lead in receptions with 16 (206 yards, one touchdown), a significant number in those defense-dominated days when most teams concentrated on running the ball. In 1935, Badgro blocked a punt and returned it for the go-ahead touchdown in a 17-6 win over the Boston Redskins.

“Red was a rugged, fierce competitor,” former Giants owner Wellington Mara once told The Seattle Times. “A 190-pound defensive end was pretty big in those days. He was a very mild-mannered guy, but murder on the field. He was a clean player. You had to be because there were only three or four officials and the other guy could get back at you without the officials catching on.”

Badgro entered the Washington Sports Hall of Fame in 1967, along with former Seattle U. basketball stars Johnny and Eddie O’Brien and jockey Basil James, and was named to the All-Time Pacific Coast Conference team in 1968.

When Badgro made the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1981, with Jim Ringo, George Blanda and Willie Davis, he was 78, making him the oldest player elected. The 45-year span between his final game, with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and his election, was also a record.

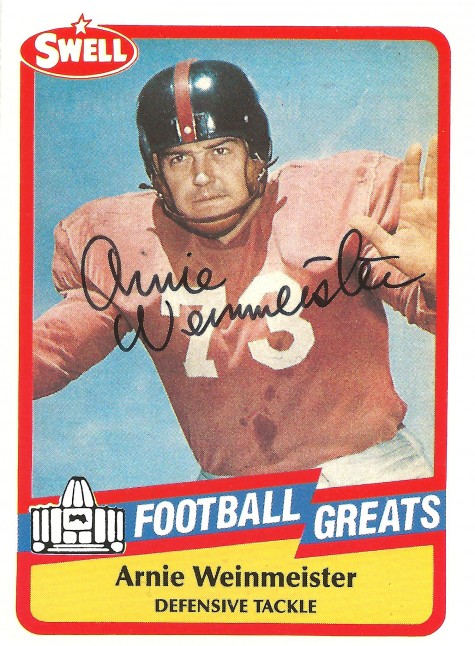

ARNIE WEINMEISTER / Class of 1984

It’s not often that a graduate of the University of Washington football program succeeds in the NFL to a far greater degree than he did as a Husky. But such was the case with Weinmeister, who went from a college career of no particular distinction – he was a 17th-round draft pick in 1945 — into an NFL career that landed him in Canton.

Weinmeister’s professional experience amounted to six seasons and 71 games, one of the shortest Hall of Fame tenures on record, but he obviously impressed a lot of people immensely.

Born March 23, 1923 to German immigrant parents in Rhein, Saskatchewan, Arnold George Weinmeister, one of eight children, moved to Portland with his family when he was a year old. He attended Jefferson High and twice was named an all-city tackle.

Weinmeister entered the University of Washington in 1941 to study math and economics and earned a football scholarship as a two-way end under head coach Ralph “Pest” Welch.

Weinmeister played one season (1942) before, as with many of his teammates, he dropped out of school to join the military. Weinmeister missed the 1943-44-45 seasons, primarily serving with Gen. George Patton’s forces in France and Germany as an artillery officer.

Weinmeister returned to the UW in 1946. After his college career ended in 1947, Weinmeister wanted to enter private business, but Ray Flaherty, a Gonzaga graduate and then the coach of the All-America Football Conference’s New York Yankees, persuaded Weinmeister to give pro football a whirl. An $8,000 contract clinched the deal.

Weinmeister joined the Yankees in 1948, played two years, then signed with the New York Giants, spending four years with the club. He made first-team All-Pro every year.

According to Pro Football Hall of Fame, Weinmeister was “one of the first defensive players to captivate the masses of fans the way an offensive ball-handler does. At 6-foot-4 and 235 pounds, he was bigger than the average player of his day and was widely considered to be the fastest lineman in pro football.

“Blessed with a keen football instinct, he was a master at diagnosing opposition plays. He used his size and speed to stop whatever the opposition attempted, but it was as a pass rusher that he really caught the fans’ attention. A natural team leader, he was the Giants co-captain in his final season in New York.”

Following his NFL career, Weinmeister spent two seasons in the Canadian Football League and then went to work for the Teamsters Union, an association that lasted until his retirement. Weinmeister entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1984 in a class that included former Seahawks president Mike McCormack. Weinmeister died June 28, 1992.

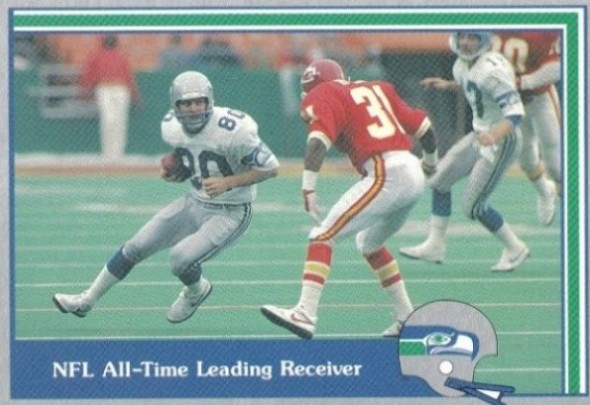

STEVE LARGENT / Class of 1995

Selected in the fourth round of the 1976 NFL draft by the Houston Oilers, Largent arrived in Seattle in a trade Aug. 26, 1976 for an eighth-round 1977 pick. The Oilers used that choice to select Georgia wide receiver Steve Davis, who never played a down in the NFL. Largent became the greatest receiver in Seahawks history, the team’s first member of the Ring of Honor, and the first former Seahawk elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

When Largent retired in 1989, after a 13-year career, he held every significant receiving record in pro football history. Though Jerry Rice subsequently broke Largent’s NFL marks for receptions, yards and touchdowns, Largent remains one of the iconic figures in franchise history – a receiver with an uncanny ability to get open and hang on to nearly ball thrown in his direction. Among his career highlights:

- Inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1995 in his first year of eligibility (23rd player inducted in first year of eligibility), becoming the first former Seahawk enshrined.

- First member of the Seahawks Ring of Honor, inducted Dec. 23, 1989, also the date of his final NFL game.

- First former Seahawk inducted into the Washington State Sports Hall of Fame in 1999.

- Retired (1989) as the NFL’s all-time leader in pass receptions (819), pass receiving yards (13,089) and receiving touchdowns (100).

- Retired as the Seahawks’ all-time leader in consecutive games with at least one reception (177), 50-catch seasons (10) and 1,000-yard seasons (8).

- Finished in the AFC (or NFC) top 10 in receptions 10 times in 14 seasons.

- Led the AFC in receptions in 1978 with 71 and finished second in the conference twice (1981, 1987).

- Finished in the conference top 10 in receiving yards seven times, and led the AFC in receiving yards in 1985.

- Selected to play in the Pro Bowl seven times – 1978, 1979, 1981, 1984, 1985, 1986 and 1987.

- First-team All-NFL by the Associated Press twice – in 1979 and 1985.

- NFL Alumni Association Wide Receiver of the Year in 1985.

- NFL Man of the Year in 1988.

- Career-high 15 catches against the Detroit Lions Oct. 18, 1987

- Career-high 261 receiving yards against the Lions Oct. 18, 1987.

- Caught three touchdowns in a game three times, last vs. Detroit Oct. 18, 1987.

- Career-long catch of 74 yards against San Diego Nov. 27, 1977.

- 40 100-yard receiving games.

The Seahawks retired Largent’s No. 80 in 1995 following his induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. No. 80 was “unretired” briefly in 2004 when Jerry Rice became a member of the Seahawks.

WARREN MOON / Class of 2006

No quarterback with ties to the state had a more profound impact than Moon, a 6-foot-3, 215-pound native of Los Angeles. After he led the Washington Huskies to the 1977 Pac-8 Championship and a victory over Michigan in the 1978 Rose Bowl, the UW program vaulted to national prominence, where, under head coach Don James, it remained for nearly 20 years.

No ex-Husky quarterback had a greater pro career than Moon. Although initially spurned by the NFL (he went undrafted and launched his professional career in the Canadian Football League), he became a perennial Pro Bowl player and first-ballot Pro Football Hall of Famer. In so doing, Moon helped usher in the era of African-American quarterbacks.

Moon became the first African-American quarterback to start in the Pro Bowl (1988), the first named NFL Man of the Year (1989), the first to lead the NFL in TD passes (1990), the first to throw for 4,000 yards in a season (1990), the first named AP Offensive Player of Year (1990) and the only one to throw for 500 yards in a game (1990). Finally, he became the first African-American quarterback elected to Pro Football Hall of Fame (2006).

Moon lasted a long time. After spending six years in the CFL, where he quarterbacked the Edmonton Eskimos to five Grey Cup titles (1978-82), he joined the Oilers as free agent in 1984 and spent and spent 17 years with Houston (1984-93), Minnesota (1996-96), Seattle (1997-98) and Kansas City (1999-00).

Moon threw for 49,325 yards and 291 touchdowns in 208 games, including 203 starts. He led his teams to seven playoff appearances, exceeded 3,000 yards passing nine times, produced 42 300-yard games, six 400-yard games and one 500-yard game. He also threw 20 or more touchdowns in a season seven times and four or more TD passes in a game nine times, including five in a game four times.

Moon was especially good late in his career, becoming the oldest quarterback in history to throw for 400 yards (1997), throw five TD passes (1997), rush for a TD (1997), win an MVP award in the Pro Bowl (1998) and throw a touchdown pass (2000).

When Moon entered Canton in 2006, he did so as the first undrafted quarterback ever enshrined and today remains the only player inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame and Canadian Football Hall of Fame.

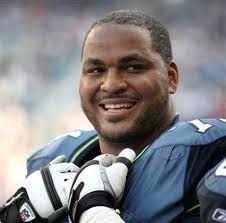

CORTEZ KENNEDY / Class of 2012

In an 11-year career with the Seahawks, “Tez” established himself as the best defensive tackle in franchise history, and also one of its most durable players, not missing a game until his eighth season. Despite facing double and triple teams, Kennedy ranked among the team leaders in tackles and sacks every year, and had his best season in 1992 when he was named the NFL’s Defensive Player of the Year on a club that posted a 2-14 record.

Multiple times an All-Pro and Pro Bowler, Kennedy was named a member of the NFL’s 1990s All-Decade team and, in 2009, became a first-time finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Although he had to wait until his fourth year of eligibility to cross the portals of Canton, there was never any question of his ultimate admission.

The Seahawks selected the 6-foot-3, 298-pound Kennedy out of the University of Miami with the third overall pick in the 1990 NFL draft. Kennedy went on to play in 167 of a possible 176 games, which included a streak of 116 consecutive games played and a club-record 100 consecutive starts.

Kennedy made first-team All-Rookie, as selected by the Pro Football Writers Association, in 1990 and was then voted to a then-team record eight Pro Bowls (1992-97, 1999, 2000). Kennedy also made first-team All-NFL three times (1992, 1993, 1994) and second team (1991, 1996) five times.

The NFL Seahawks made Kennedy, who spent his entire career with the franchise, the 10th member of their Ring of Honor Sept. 17, 2006.

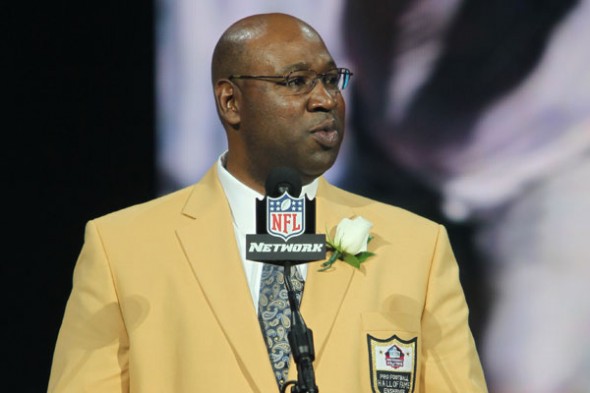

WALTER JONES / Class of 2014

The most decorated offensive lineman in Seahawks history, the 6-foot-55, 315-pound Jones made nine Pro Bowl teams (franchise record) in his first 12 years with the team, only one reason why he entered Canton on his first attempt.

In addition to being the first Seahawks’ offensive lineman voted to play in the Pro Bowl, Jones was named first-team All-Pro by The Associated Press a franchise-record four times. He played a significant role in springing Shaun Alexander loose for more than 100 NFL touchdowns, and for helping quarterback Matt Hasselbeck earn three Pro Bowl invitations.

Jones played in 180 games through 2009, starting every one. He failed to get on the field in 2009 due to bad left knee, and was unable to rehabilitate to the point that he could play again. The Seahawks announced Jones’ retirement April 29, 2010, and immediately retired his No. 71 jersey.

The NFL selected Jones to its 53-man All-Decade Team (2000s) Jan. 31, 2010.

Among Jones’ numerous highlights: He anchored a line that enabled Shaun Alexander to score an NFL-record five first-half touchdowns against Minnesota Sept. 29, 2002.

He was part of a line that helped the Seahawks amass a club record 320 yards rushing against the Houston Texans Oct. 15, 2005.

He finished his 13-year career having surrendered just 23 sacks (according to coaches statistics) in 5,703 pass attempts and was called for holding just nine times (same number of Pro Bowl selections).

His signature play occurred in the 2005 NFC Championship Game at Qwest Field, when Jones blocked Carolina defensive end Mike Rucker about 15 yards downfield and then dropped him near the goal line, allowing Shaun Alexander to score a touchdown.

At the time of his retirement, Jones was the last remaining Seahawk to have played in the Kingdome.

“He’s the best offensive lineman, clearly, that I’ve ever had,” said Mike Holmgren, who coached Jones for 10 years in Seattle. “He was a phenomenal player.”

“He dominated people. He dominated every single play and every single game,” said former Seahawk Ray Roberts. “He totally took his man out of the play. He’s easily one of the top two or three tackles of all time, and in my opinion he’s the greatest Seahawk ever.”

—————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Good work as always, guys. Nice to see the state well-represented in Canton. Some real studs here. He’s pretty much forgotten now, but Hein was a truly exceptional lineman.

I suppose he doesn’t qualify for this list because he made the Hall of Fame only two years after coming to Seattle and it was as a player, but Mike McCormack maybe deserves an asterisk because he DOES have local ties due to his seven-plus years with the Seahawks and you have to think he played a role in the team’s initial era of success on the field (along with Chuck Knox, who might deserve a bust in Canton himself).

Excellent work. Enjoyed becoming familiar with Washington’s football HOF connections.