The Washington-UCLA football series, which resumes for the 72nd time Saturday at Montlake, dates to Dec. 3, 1932, when the Huskies posted the first of four consecutive shutouts, a 19-0 victory in Los Angeles. The Bruins’ first victory in the rivalry was in 1938, also in Los Angeles, and in 1939 brought a unique — for the era — collection of athletes to Seattle to face a UW team coached by Jimmy Phelan.

——————————————

By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

The 15,017 spectators that showed up for the Washington-UCLA matchup on the overcast afternoon of Oct. 7, 1939 saw something that day that most in attendance probably thought they’d never see: Three African-Americans starting in the Bruins’ single-wing backfield.

Washington at the time had virtually no history with black football players. Johnny Prim, about whom little is known, played on coach Stub Allison’s 1920 team, but never lettered. Hamilton (Ham) Greene lettered in 1921 under new head coach Enoch Bagshaw and blocked a punt that set up the Huskies’ lone field goal in the school’s worst-ever defeat, 72-3 to California.

After Greene, UW carried no more black players on its roster until 1937 when Garfield High graduate Charlie Russell became the second black player to letter – barely. Russell didn’t play much until the season’s fifth game, a 13-7 loss to Stanford, when his performance warranted the attention of Seattle newspapers.

“Charlie Russell, the twisting, squirming, hot-footed Negro boy from Garfield! What a grand game he played and what an ovation he received as, tired and weary, he finally dragged his bruised body from the battle scene,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer editorialized.

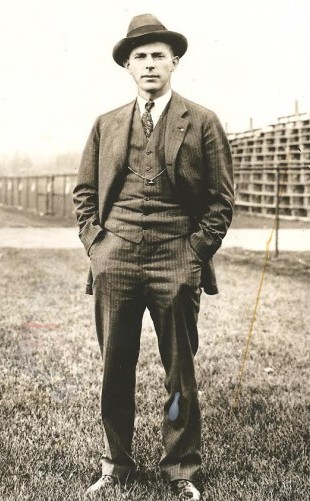

Russell nearly scored a touchdown, but head coach Jimmy Phelan, as he usually did, took out Russell before he had the opportunity.

“Maybe Phelan didn’t want a black to score a touchdown,” Russell told an interviewer in 1990. “I honestly feel that he was a very prejudiced man and nobody will ever convince me otherwise.”

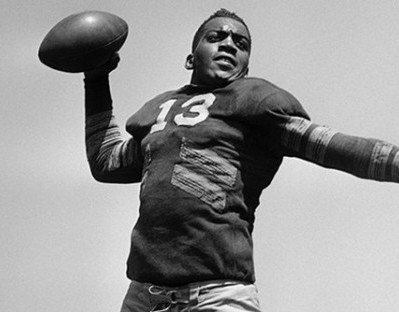

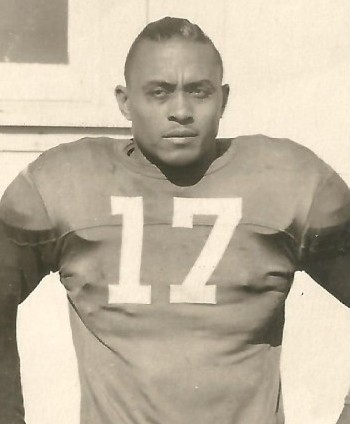

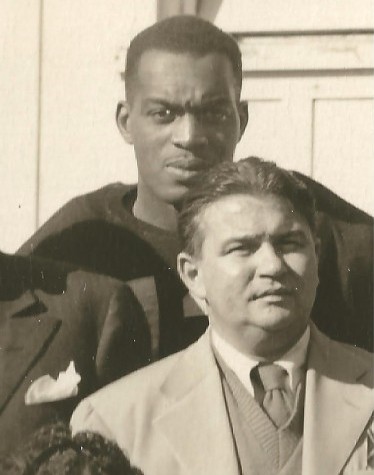

UCLA had no problem showcasing black players. The Bruins had three of the best on the West Coast – left halfback Kenny Washington, receiver/halfback Woody Strode and a newcomer from Pasadena Junior College, wingback Jack Robinson.

Phelan’s Huskies were already familiar with Washington, who had a hand in both UCLA touchdowns in its 13-0 victory over UW in 1938, and Strode, a member of the Bruins varsity since 1937 and a world-class decathlete. But they didn’t know much about Robinson, so Phelan dispatched his top assistant, Ralph Welch, to Los Angeles to watch UCLA play Texas Christian the week before the Bruins came north to face the Huskies.

“Ralph Welch, assistant coach and No. 1 scout on Phelan’s staff, watched UCLA defeat Texas Christian last Friday night in Los Angeles, 6-2,” reported Seattle Times columnist George Varnell. “Welsh says that Jack Robinson is as good as he has been touted, being dazzlingly shifty. The addition of Robinson to the UCLA backfield also adds effectiveness to Kenny Washington’s play, giving the Bruins two of the fleetest backs in the conference.

“UCLA’s new coach, Babe Horrell, has devised reverses, double reverses and split bucks to shake loose Robinson and Washington. The Huskies defense must be air tight to stop them.”

On Wednesday of game week, The Times published a lengthy profile of Jack Robinson that said, in part:

“John Robinson, No. 28. Height: 6 feet. Weight: 180. Residence: Pasadena. That’s the way the Negro is listed on the roster of UCLA, the Huskies’ football foe of the moment. Last year, Robinson dazzled Southern California junior college foes so successfully, while playing for Pasadena Junior College, there were packed crowds upward of 50,000 fans any Saturday Robinson was slated for action.

“Athletic ability must run in the Robinson family, for Jack’s older brother Mack made the Olympic Games (1936) as a sprinter and broad jumper from the University of Oregon (finished second behind Jessie Owens in the 200 at Berlin).

“The younger Robinson made his collegiate debut last week and the fact that he averaged almost 10 yards per play in six ball-carrying attempts played a big part in UCLA’s surprise 6-2 victory over Texas Christian.

“The Bruins are the favorites thanks to the running and pitching of a pair of Negro halfbacks, Robinson and Washington, but they’re facing a Washington team vastly superior to the one that bowed to Pittsburgh last Saturday.

“Washington, a slim Negro halfback, is Horrell’s scoring ace. Washington passed and ran UCLA to victory over the Huskies last year in Los Angeles 13-0. Robinson is known mostly as a ball carrier but watch him pitch a few passes.”

Robinson did pitch a few, and added a few other wrinkles, as Alex Schults explained in his game story in The Times.

“Just when the Washington Huskies thought they had their first 1939 Pacific Coast Conference football battle won yesterday in the Stadium, the Midnight Express from UCLA got rolling, with Engineer Jack Robinson tooting the whistle, and it wasn’t long until what looked like a 7-0 Washington victory became a 14-7 defeat,” Schultz wrote. “Three great Negro stars, Robinson, Kenny Washington and Woodrow Wilson Strode, wrecked the Huskies in the second half. The Huskies knocked Engineer Jack down and jumped on him in highly approved fashion throughout much of the first half. But the slim Negro halfback kept getting up.

“When he wrapped his arms around the pigskin, booted downfield by the mighty toe of Dean McAdams early in the third period, man, oh, man, how that lad did ramble. Forty-three yards McAdams tooted this particular punt, and there wasn’t a purple jersey handy when Robinson tucked it away on the UCLA 31-yard line.

“Into midfield went the speedster. He slid past a dozen reaching Husky arms to hug the south sideline and was clear of the pack with a couple of protectors about him when he passed the Washington 40-yard stripe. Twenty yards along, McAdams angled over and cracked Robinson hard enough to make him stumble. Another 10 yards and Bill Marx caught up, spilling Jack on the six-yard line. From there, it wasn’t difficult for UCLA to rush for the tying touchdown. “

“That run of Robinson’s beat us,” said Phelan. “Until that occurred we had the game well in hand.”

Schults included one paragraph in his game story that would not be published today. We include it only to show what was acceptable 75 years ago. After describing how Robinson left the game with an ankle injury, Schults wrote:

“There will be fried chicken and watermelon on the dining car table and the Pullman porters will lug in hot water by the barrel to keep Jack Robinson’s ankle warm on the homeward ride. The Huskies groan with the thought that while Strode and Washington will hang up their moleskins after this season, the shadow of Robinson will hang over them for two more years of conference football.”

In UCLA’s 14-7 win, Robinson rushed for 65 yards and returned the punt Phelan lamented over for 63. He didn’t score a touchdown, but kicked both of the Bruins’ extra points. The Huskies saw Robinson only one more time, Nov. 23, 1940 in Los Angeles, where Robinson rushed for 66 yards and completed seven of 14 passes for 129 yards.

By then, Robinson was a UCLA legend, the only athlete in Bruins’ history to letter in four sports – football, basketball, baseball and track.

In football, Robinson led the nation in punt return average in 1939 (16.5 yards) and 1940 (21.0 yards) and his career average of 18.8 still ranks fourth in NCAA history. During his senior year, he led UCLA in rushing (383 yards), passing (444 yards), total offense (827 yards), scoring (36 points) and punt returns.

As a basketball player, Robinson led the Pacific Coast Conference’s Southern Division in scoring in 1940 (12.4 average in 12 league games) and 1941 (11.1 in 12 league games) and was named All-PCC Southern Division in 1940.

Robinson had an abbreviated track career but won the NCAA title in the long jump (24-10¼) as well as at the Pacific Coast Conference meet (25-0).

Jack Robinson also won swimming championships at UCLA and reached the semifinals of the national African American tennis tournament.

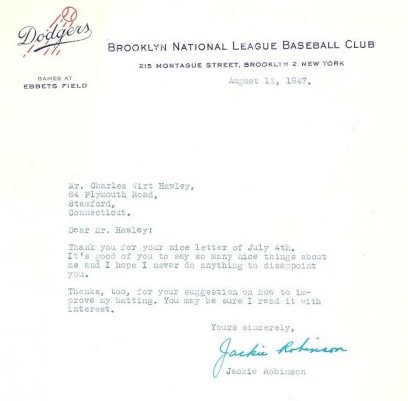

Oddly, baseball was Robinson’s weakest sport at UCLA. He had four hits and four stolen bases, including home, in his first college game (March 10, 1940), but otherwise batted .097. The odd part is that he is most famous today as a baseball player. Sports writers didn’t start calling Jack Robinson “Jackie” until after he became a professional in the Dodgers organization.

The 15,017 fans that filtered into Husky Stadium that gray October day could not have imagined that Jackie Robinson would break baseball’s color barrier eight years later, April 15, 1947. But Robinson was only of only three barrier breakers for the Bruins that day.

A year before Robinson made history wearing the uniform of the Dodgers, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode became the first post-World War II African Americans to sign National Football League contracts.

After Washington graduated from UCLA in 1940, Chicago Bears owner George Halas attempted to sign him but was blocked by NFL owners, particularly George Preston Marshall of the Washington Redskins.

With nowhere else to go, Washington played for the Hollywood Bears and San Francisco Clippers of the Pacific Coast Professional Football League from 1941 to 1945. In 1946, when the Cleveland Rams relocated to Los Angeles, the commissioners of the L.A. Coliseum stipulated that as part of relocation the team had to be integrated.

Washington became a Ram March 21, 1946, ending the Marshall-orchestrated ban that had kept blacks from playing in the NFL since 1933 (17, including future Hall of Famer Friz Pollard and Paul Robeson, played between 1920-32). As part of Washington’s agreement, the Rams had to sign his best friend, Strode, who also played for the Hollywood Bears. Strode inked May 7.

Ohio State guard Bill Willis (Aug. 6) and Nevada fullback Marion Motley (Aug. 9) followed Washington and Strode into pro football when they both signed with the Cleveland Browns of the All-America Football Conference.

Washington’s NFL career lasted only three years, mostly because his knees were shot after five surgeries. He still managed to average 6.1 yards per carry and in 1947 scored on a 92-yard run against the Chicago Bears, still a Rams record.

Washington retired after the 1948 season and UCLA retired his No. 13 jersey in 1956, the same year he entered the College Football Hall of Fame.

Strode played one year for the Rams (1946) and two for the Calgary Stampeders before embarking upon a career as a professional wrestler and actor. He had a Golden Globe-nominated role in Spartacus (1960), played villains opposite three Tarzans (Gordon Scott, Jock Mahoney, Ron Ely), and appeared in The Ten Commandments (1956), Pork Chop Hill (1959) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). His last film was The Quick and the Dead (1995).

Strode also had parts in dozens of TV shows, including Jungle Jim (1955), Rawhide (1961), The Farmer’s Daughter (1964), Daniel Boone (1966), Batman (1966), Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979), The Dukes of Hazzard (1980) and Fantasy Island (1981).

Due to pro football’s low national profile in the 1940s and 1950s, neither Washington nor Strode achieved Jackie Robinson’s athletic fame. He became the first African American named Rookie of the Year (1947), the first named Most Valuable Player (1949), and the first elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame (1962).

Robinson is also the only player in modern major league history (since 1920) to swipe second, third and home on three consecutive pitches (1954).

But while Robinson starred on the diamond, baseball might not have been his best sport. Among his non-baseball feats:

- 1: Singles titles Robinson won in the Pacific Coast Negro Tennis Tournament (1936).

- 1: Times that Robinson represented UCLA in the NCAA Swimming & Diving Championships.

- 2: MLB players who have received the Congressional Gold Medal: Robinson and Roberto Clemente.

- 3: Number of sports in which Robinson was named All-America — football, basketball and track and field.

- 3/1/1: Rushing TDs, passing TDs and interceptions by Robinson against Washington State Nov. 16, 1940.

- 4: Letters won by Robinson in 1939 (football, basketball, baseball, track), making him UCLA’s first four-sport letterman.

- 12.24: Robinson’s yards-per-play average in 1940, when he led the UCLA football team in rushing and passing.

- 12.4: Robinson’s basketball scoring average at UCLA in 1940, which led the PCC’s Southern Division.

- 16.5: Robinson’s punt return average for the UCLA football team in 1939, a figure that led the nation.

- 18.8: Robinson’s career punt-return average during his two seasons at UCLA, which still ranks fourth in NCAA history.

- 24-10¼: Distance of a Robinson long jump at the 1940 NCAA Track and Field Championships, good for first place.

- 25-6½: Distance of Robinson’s best long jump while he attended Pasadena JC, prior to enrolling at UCLA.

- 26-0: Distance of Robinson’s longest long jump (then known as running broad jump) at UCLA (1940).

- 42: Jersey number worn by Robinson, who said, “No American is free until every one of us is free.”

- 43: Distance, in yards, of a Robinson pass reception against Washington Oct. 7, 1939 at Husky Stadium.

- 1975: Year that Willie Mays said, “Every time I look in my wallet I see Jackie Robinson.”

- 1999: Year that Robinson was named by Time Magazine as one of the “100 Most Important People of the Century.”

One more thing about Jackie Robinson. In 1942, Robinson put athletics on hiatus and enlisted in the U.S. Army. Serving in Texas, Robinson was court-martialed (eventually acquitted) for refusing to move to the back of a military bus — 13 years before the world ever heard of Rosa Parks.

——————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com

1 Comment

“After (Kenny) Washington graduated from UCLA in 1940, Chicago Bears owner George Halas attempted to sign him but was blocked by NFL owners, particularly George Preston Marshall of the Washington Redskins.”

Consider the irony of keeping an African American out of the NFL by a man who owned the Redskins. In fact, the Redskins were the FINAL professional American football franchise to integrate, and not until 1962.