By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

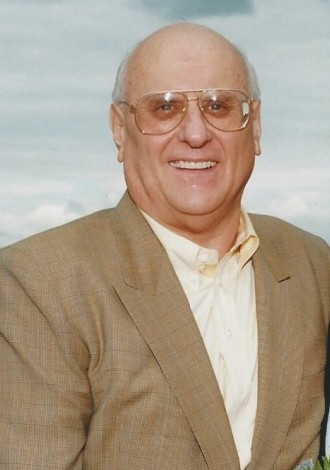

He never hoisted the 12th Man flag nor threw out a ceremonial first pitch. He is not in any Hall of Fame or Ring of Honor. But no individual did more to shape modern professional sports in the Pacific Northwest than Herman Sarkowsky, whose DNA is buried in the histories of four of the region’s franchises, as well as its largest race track.

“Just my opinion, but Herman is the most important athletic figure in the history of this state, and maybe in two states. Without Herman, everything we know today would have been different, if it had been at all.”

Dick Vertlieb made that assertion on a Seattle radio program two decades ago, bringing to his view the bona fides of a franchise virtuoso. Vertlieb secured an NBA team for Seattle in 1967, consulted on the 1974 acquisition of the Seahawks, was among 10 original investors in the Sounders, and helped launch the Mariners, serving as their first general manager.

Sarkowsky trumped even the iconic Vertlieb. He put together the deal that brought the Trail Blazers to Portland, was a partner with Vertlieb in the Sounders, and effectively created the Seahawks.

Without Sarkowsky’s intervention on behalf of the Mariners, Edgar Martinez never would have doubled into the left-field corner of the Kingdome, and the ensuing home-plate pileup that inspired Safeco Field would not have taken place.

Pete von Reichbauer represents South King County (District 7) on the King County Council and played the key political role in the Seahawks’ change of ownership from Ken Behring to Paul Allen in the mid-1990s.

“Herman was among those self-made men who climbed to the top of the mountain and never forgot how he got there,” said von Reichbauer. “Herman made things happen, and he did it not with a golden touch, but a platinum touch.”

“In the last 70 years, Herman was one of the icons,” said Ron Crockett, president of Emerald Downs and a major donor to University of Washington athletics and academic programs. “No question about it.

“If you think of the wide variety of things he did and the many lives he affected, it’s just amazing. Most of us have a career. Herman had several, all different in a way, and all were great.

“I won’t even go into the details, but within the last year I had a personal situation. I called Herman and said, ‘What would you do in this case?’ And then I presented the case. Herman told me what he would do, and so that’s what I did.

“Herman was always the first guy people went to if they had an idea. I think half the startups in town went through him. He was a brilliant and humble man. Whenever I reached a quandary on something, I’d call Herman.”

Howard Wright is the founder and chair of Seattle Hospitality Group, which provides comprehensive corporate meeting and event management (trade show, conference, convention, retreat) worldwide.

“My parents and Herman were friends in the horse racing community,” Wright said. “My mother is a thoroughbred breeder, my father was the state tacing Commissioner for a time. Herman was a thoroughbred investor. He always had a keen sense of opportunity and wouldn’t be boxed in by conventional thinking. He took calculated risks and had a willingness to be open to new friends.”

Sarkowsky is part of a special pantheon of Northwest-based athletic movers and shakers that stretches to the turn of the 20th century when former major league catcher Dan Dugdale arrived in Seattle en route to the Klondike gold fields, thought the better of it, and made the city a baseball town (see Wayback Machine: Seattle Struck Gold In Dugdale).

Dozens of Dugdale’s ilk followed, including Joe Gottstein, who built his racetrack (Longacres), and Emil Sick, who constructed his ballpark (Sicks’ Stadium). Down the road, Paul Allen financed a statewide election to make CenturyLink Field a reality, ironically winding up owning (or sharing in ownership) three franchises (Blazers, Sounders, Seahawks) previously owned by Sarkowsky.

Sarkowsky owned his teams in a different way than most who followed. An anti-Mark Cuban who saw no need to call attention to himself, Sarkowsky didn’t dance on dugout roofs as George Argyros did, didn’t call the newspapers and threaten to trade his entire team, as Sam Schulman did, and didn’t threaten to have reporters arrested, as did Barry Ackerley. Sarkowsky never went on record about Clay Bennett, but surely would have been appalled if he had.

“Another thing: Herman never said one bad thing about anybody and, as far as I know, nobody ever said one bad thing about him,” said Dave Heerensperger, also a thoroughbred connoisseur. “How many people can you say that about?”

David C. Wyman did business, invested in thoroughbreds and boated the waters of Alaska and British Columbia with Sarkowsky for more than two decades.

“No. 1, he was very sharp. No. 2, he was a man of high integrity,” said Wyman. “He didn’t have any need for personal publicity, but whatever he got involved in, he got involved in with both feet and both hands and gave everything he had to it.”

“Herman was visible and invisible,” added von Reichbauer. “Everyone on the inside knew him, but he always kept a low profile. You never saw him doing a Ken Behring or acting like some of the other owners we’ve had around here that needed to be front and center. He was a classy, classic owner. He hired good people, set goals and allowed people to meet them.”

And yet Sarkowsky, businessman, real estate developer, investor, consultant, financial oracle, philanthropist, career board member, patron of the arts, and unabashed sports fan, had the heart of a “riverboat gambler,” in son Steve Sarkowsky’s words, and a genius for deal making.

Norm Rice served as Seattle’s mayor from 1989-97 after a long career on the Seattle City Council.

“Liberal Democrat that I am, I didn’t run in the kinds of crowds Herman did, and I didn’t know all his connections or how he financed things, but I know he was very astute,” said Rice. “If you had an idea, you’d want to run it by Herman.

“Herman was a gambler who always went after the deal. He won some and lost some, but was always willing to take a chance. His reach and depth were amazing.”

“He thrived on the thrill of the chase,” said Geri M. Kraft, who had a nearly five-year involvement with Sarkowsky during his real estate development days before forming her own company, Kraft Office Properties. “That was a day in the life of Herman Sarkowsky.

“He always saw the big picture. Whether it was housing development, where he made his original fortune, or office building development, or sports teams or horse racing, he was able to see there was a need for something. He was willing to take a risk, jump in and make things happen.”

“He was one of the smartest people around,” said John Nordstrom, “and great to work with.”

An entrepreneur who turned Pay ‘n Pak into a home improvement retail colossus and followed by creating the regional chain Eagle Hardware & Garden, Heerensperger knew Sarkowsky for decades as a businessman and horseman. Heerensperger visited Sarkowsky once a week for several months prior to Sarkowsky’s Nov. 2, 2014 death at 89.

“Darn he was smart,” said Heerensperger. “He was on my board at Eagle Hardware. He didn’t talk that much, but when he said something everybody listened. He had unbelievable influence.”

Born in Gera, Thuringia, Germany, June 9, 1925, Sarkowsky fled with his family to Czechoslovakia, and ultimately the U.S., in 1934 when his father, Irving, “saw the handwriting on the wall” after Adolph Hitler launched his persecution of European Jews.

The family – Irving, wife Paula, Herman and brothers Fred and Leo – eventually settled in Seattle, where Irving set up shop, initially in the fur business. Herman didn’t speak a word of English, which proved no handicap at all.

Reared on Capitol Hill, he attended Broadway High School, where he served as sports editor of the student newspaper, patterning his column, “The Water Boy,” after the work of Royal Brougham, sports editor of The Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Following a tour in the Army Signal Corps during World War II, Sarkowsky enrolled at the University of Washington, graduating with a B.A. in business in 1949, then went to work for William Spivock, a Northern California home builder who assigned the young Sarkowsky to develop an 80-house tract near Lincoln High in Tacoma.

Upon completion of the job, and starting with a reported stake of $7,000 in 1952, Sarkowsky founded United Homes Corporation. By 1969 – at 44 — he was the most successful builder of single-family dwellings in the Pacific Northwest. He ultimately sold to ITT.

Sarkowsky began investing in thoroughbreds in 1960 — his first purchase was a $2,000 claimer Forin Sea, in partnership with Longacres-based trainer (and eventual racing secretary) Glen Williams – and received his first opportunity to buy into a pro team during a meeting with Vertlieb.

Vertlieb received a call from Harry Glickman, heading an effort to start an NBA franchise in Portland. Glickman told Vertlieb that financing had fallen through and that he needed a bailout to meet the NBA’s purchase deadline.

Vertlieb put the phone down and asked Sarkowsky if he wanted to loan Glickman $1 million.

“I said I wasn’t interested in loaning the money — I wasn’t a bank — but I might be interested in buying,” Sarkowsky told The Seattle Post Intelligencer. “It was purely a spur-of-the-moment decision.”

Sarkowsky asked for majority ownership and got it. He never revealed the sum he received for selling United Homes, but apparently didn’t blink at plopping down $3.7 million on the Blazers. That was 1970. Herman was 45.

Sarkowsky owned the franchise entirely for about a week, and then brought in Larry Weinberg of Los Angeles and Bob Schmertz of Lakewood, NJ., fellow real estate developers, as partners (Schmertz subsequently owned the Boston Celtics). Sarkowsky headed the trio, acting as president and managing partner of the expansion franchise.

Sarkowsky had a candid assessment of his early years with the Blazers during a 1973 interview with the Seattle Times.

“We did everything wrong,” he admitted. “Harry Glickman and I, well, neither of us had experience in basketball. We compounded that weakness by hiring a director of personnel who had never been in the NBA, who then helped us select a coach who had never been in the NBA, who helped us select other people who had no NBA experience.”

Typical of expansion teams, Portland struggled in its first few years, but in 1974 Sarkowsky won a coin flip and wisely drafted Bill Walton, the sprout-eating hippie from UCLA, over Marvin “Bad News” Barnes of Providence, with the No. 1 pick. Walton immediately ignited Blazermania.

Sarkowsky loved the Blazers: An Eastsider (and in another information age), he used to drive to the top of Clyde Hill with son Steve in order to pick up their games on the radio. He probably never would have sold had it not been for another investment opportunity.

“(NFL Commissioner) Pete Rozelle had a rule that you couldn’t own teams in different leagues,” Steve explained. “My dad hated to get out of the Blazers because they were near and dear to his heart. Obviously, the rules have changed. Today guys own multiple teams and nobody cares. But back then it couldn’t be done. While the basketball team was tough to get rid of, dad really believed in the Seahawks opportunity.”

Various investors – and investment groups – angled to bring pro football to Seattle since the mid-1950s. But nothing came those efforts until after Feb. 13, 1968, when King County voters passed a massive civic-improvement project called Forward Thrust. It included $40 million in bonds for a King County Domed Stadium, which not only made it possible for Seattle to host pro football, but satisfied Major League Baseball’s requirement for a ballpark to accommodate the expansion Seattle Pilots.

The yes vote on the domed stadium resonated all the way to Minneapolis, where Twin Cities tycoon Wayne Field, who always lusted for an NFL franchise, steered his sights toward Seattle, and took action. In February 1969, he formed Seattle Sea Lions Management Corp.

Field possessed all the credentials for a future NFL owner except one: He was not Seattle-based, a league requirement. To circumvent that, Field aligned himself with Hugh McElhenny, then working for Allen & Dorward, a San Francisco advertising firm, and a University of Washington football legend.

Field hired McElhenny Dec. 17, 1971 as vice-president, GM and face of the Sea Lions with the proviso that McElhenny would become a minority owner if the NFL awarded Seattle a team. Field and McElhenny then re-christened their venture the Seattle Kings and set about to convince the NFL to award them a team (see Wayback Machine: Hugh McElhenny and the Kings).

After two years of wooing NFL owners, two conclusions seemed foregone: Seattle would be awarded a franchise, and Field/McElhenny would be the owners. The only question was how much they would have to pay for the privilege.

But on June 14, 1972, Field/McElhenny received a seismic jolt when a rival ownership group materialized.

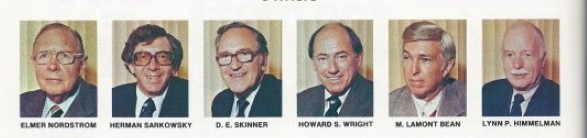

Along with shipping heir Ned Skinner, Sarkowsky had quietly assembled a who’s who of Seattle’s elite: Howard S. Wright, a Seattle contractor and a major operative in the Seattle World’s Fair; Lamont Bean, president of Pay ‘n Save; Lynn Himmelman, chairman of Western International Hotels, and Morris Alhadeff, president of the Washington Jockey Club. Collectively, they represented Seattle Professional Football (SPF).

Even McElhenny conceded that SPF was a perfect cross section of the Seattle establishment. The group was heavy with business success, civic achievement and personal prestige. Money? No problem.

The NFL awarded Seattle a franchise June 4, 1974 without disclosing which potential ownership group – McElhenny’s or Sarkowsky’s – would own the team. Sarkowsky soon emerged as the spokesperson for SPF, creating the impression that if his group received the NFL’s blessing he would serve as majority owner.

McElhenny and Field assumed the franchise fee would be $10million-$11 million. But when the NFL placed it at $16 million, that was too rich for their blood and they reluctantly dropped their ownership bid and threw their support behind SPF, which covered the $16 million entry fee with $2.6 million payments in 1974 and 1975 and $10.8 million spread over the next eight years.

After Alhadeff withdrew from SPF, correctly figuring the NFL wouldn’t accept his involvement in thoroughbred racing, Sarkowsky sought out the Nordstrom family as a replacement. Rozelle ultimately ruled that the family’s multiple investors constituted 51 percent of SPF, so they became majority owners, which was fine by the 49-year-old Sarkowsky, who assumed a roughly 10 percent stake in the franchise.

“Obviously, many ingredients went into the successful awarding of the NFL expansion to the Seattle group. The Nordstroms stepping up to take 51 percent was critical,” said Wright.

“But they, and I, will tell you that it was Herman Sarkowsky’s ‘bona fides’ that was significant in securing the deal, and then acting as the long-time managing partner. He brought experience from the Trailblazers and the (original) Sounders. No one else in the partnership had that kind of experience.”

“He was critical to the early organizational success of the franchise,” added von Reichbauer.

Sarkowsky (he hired the team’s first GM, John Thompson), remained as managing partner until Feb. 24, 1982, when he stepped down, according to his statement to The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, to focus on “other interests.”

Sarkowsky had plenty in the works. Along with Seahawks partners Bean, Himmelman, Wright, John Nordstrom and Jack McMillan, plus Vertlieb, Walter Schoenfeld and Lester Smith (Schoenfeld and Smith later became part of the Mariners’ initial ownership group), Sarkowsky was among the original investors in the first Sounders franchise (1974).

“It was a minor investment for us, really,” said Nordstrom.

It proved exceedingly shrewd for two reasons. It successfully curried favor with Lamar Hunt, who not only owned three teams in the new North American Soccer League, but more importantly, served as the head of the NFL Expansion Committee. The original Sounders regularly sold out Memorial Stadium, then played to crowds that, on average, eclipsed those of the Mariners after the Sounders relocated to the Kingdome in 1976.

Major League Soccer took that data into account when it examined Seattle’s potential as an MLS destination prior to awarding the city a team in 2007.

Three years after his Sounders investment, Sarkowsky purchased his first piece of downtown real estate, and in 1981 started planning a high rise that would become the $200 million AT&T Gateway Tower (now Seattle Municipal Tower) at Fifth Avenue and Columbia. Kraft came aboard as a vice president on the project.

“Herman was the kind of guy who, if he respected you, let you do your work. He took risks, but trusted the people he brought together for their expertise and let them do their jobs,” said Kraft.

Through little fault of his own other than unfortunate timing attributable to a soft real estate market, the AT&T Gateway Tower didn’t work out as Sarkowsky hoped. Some in the Sarkowsky family, and several of his friends, simply still call it “that goddamned building.”

Not much else Sarkowsky touched warranted a cuss. He and his family invested in a Howard Schultz company that bought out Starbucks, and Sarkowsky became a partner in Frederick & Nelson before selling to developer David Sabey. With long-time friend Wyman, he partnered in a number of enterprises, typical of Sarkowsky’s investment range.

“I was in business with him in Rainier Ice and Cold, primarily a cold storage plant for the seafood industry,” said Wyman. “We also had a business called S&W Aircraft Leasing. We owned aircraft and leased them out to customers in the Northwest. Both businesses were very successful. As a side benefit, we used our planes to travel to football games and Super Bowls over the years. Herman was also involved in a lot of businesses as a kind of silent partner.”

A man in demand, Sarkowsky served on an array of boards, among them the National Association of Home Builders, WebMD, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle Foundation, Seattle Repertory Theater, Seattle Symphony and United Way. He also worked tirelessly on behalf of the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle and PONCHO (Patrons of Northwest Civic, Cultural and Charitable Organizations).

He had additional involvements at UW, including president of the Alumni Fund, chairman of the President’s Club, trustee of the Alumni Association and chairman of the Hospital Board.

Sarkowsky nearly became a UW regent in 1984. Nominated by Republican governor John Spellman, Sarkowsky was displaced in a political maneuver before confirmation when Democrat Booth Gardner beat Spellman in the general election.

“The university would have been better off with Herman on the Board of Regents,” said von Reichbauer. “I always felt badly that Booth supported the guy who was his biggest campaign donor. Herman served (for approximately a year) on the board and then stepped down. The university is the lesser for it.”

Said Martin J. Wygod, chairman of WebMD: “Herman enriched Seattle not only through his work as a developer, but through his philanthropic endeavors, whether involving his alma mater, the Seattle Art Museum, or the numerous other charities and cultural institutions he was involved with, all of which will continue to benefit his community for years to come.”

“Everybody likes to leave a mark. I’ll have more than one,” said Sarkowsky, not nearly through with his opportunities.

About the time Sarkowsky stepped down as managing general partner of the Seahawks, he had a chance to purchase the Sonics from Schulman, but declined, setting up a sale of the team to Ackerley.

“He didn’t do it because the Sonics were such a financial mess,” said son Steve. “Plus, he had deep allegiance to the Blazers. It would have been an unbelievable slog to buy the Sonics from Sam and try to make it work.”

Sarkowsky’s ownership in the Seahawks officially ended July 15, 1988, when the Nordstroms bought out their minority partners, clearing the way for an unencumbered sale of the franchise to Californians Keb Behring and Ken Hoffman. The minority partners cashed out rather than expose themselves to the whims of new majority owners — a smart move given Behring’s subsequent boobery.

“I think Dad regretted leaving the Seahawks,” said Steve. “But he knew things were changing. It was really the Nordstroms that wanted to do it (sell) and (as majority owners) they were driving the deal.”

Three years later, Sarkowsky found himself, along with John Ellis of the Puget Power electric utility, the designees of Mayor Rice to come up with a plan to keep the Mariners from vamoosing to Florida. Owner Jeff Smulyan placed Seattle’s political and business leadership on notice that it had 45 days to bail him out of a financial jam.

Security Pacific Bank called in a $39.5 million note, on which Smulyan was paying $4 million annually to service the debt. Smulyan needed a lifeline or would have to either sel or move the club.

“We needed a strong and prestigious group of people to start this effort,” said Rice. “Getting Herman and John Ellis was a coup. I wanted credibility, people who were astute and well connected, and understood sports franchises.

“Herman had his background with the Seahawks and the Portland NBA team and had been a major figure in sports for a long time. And John was very strong in the business-roundtable area. I couldn’t think of two better people to start that journey.”

Sarkowsky accepted what seemed an impossible task Sept. 20, 1991, when he met with Smulyan and asked him to spell out his financial needs. Sarkowsky told Smulyan he needed specifics, not vague generalities, a Smulyan specialty.

Once Sarkowsky and Ellis got a grasp on Smulyan’s situation (Sarkowsky described the Mariners as a “financial basket case”), they conjured a plan to boost the club’s revenues by $13.5 million annually through increased advertising on Mariners’ broadcasts, a new cable TV deal and a doubling of season-ticket sales.

Smulyan told Sarkowsky he thought $13.5 million was far-fetched. But Sarkowsky didn’t do far-fetched. He and Ellis summoned Jim Thorpe, chairman of Washington Natural Gas Co.; Luke Helms, Seafirst Bank chairman; George Duff, president of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce; Harold Carr, a Boeing vice president; George Walker, U.S. West; Denny Heck, Gov. Booth Gardner’s chief of staff; King County Prosecutor Norm Maleng and Deputy Mayor Bob Watt, then put them to work.

“Dad could pack a big punch,” said Steve. “He had street cred and people took his calls. I think it had to do with his sense of community. My dad wasn’t a huge baseball fan, but he supported all of the teams because he believed strongly in what they brought to the community.”

The effort proved a tooth pull, but Sarkowsky and Ellis finally received commitments for nearly $13.5 million. Sarkowsky recognized that wouldn’t be sufficient to weld the Mariners to Seattle, but it eased Smulyan’s short-term problems and sent a message to Major League Baseball that Seattle was a viable city.

The fundraising effort also bought time to work out the only permanent solution: The sale of the franchise to local buyers.

U.S. Sen. Slade Gorton is generally credited with saving the franchise by introducing the Hiroshi Yamauchi, president of Nintendo of Japan, to a local investor group that became The Baseball Club of Seattle. With Yamauchi the lead investor, the franchise was purchased from Smulyan. Take nothing away from Gorton’s contribution, but . . .

“If we hadn’t had Sarkowsky and Ellis doing their work, we never would have made that contact,” said Rice. “They gave us access to places we needed to be and without them there wouldn’t have been anything for new owners to invest in. They made an investment in the Mariners, including the investment by Yamauchi, worthwhile.”

Sarkowsky never said much about the role he played in the behind-the-scenes drama that kept the franchise from relocation, so it went largely unreported that he was not paid for his efforts, nor that he flew civic leaders to New York at his own expense to lobby Major League Baseball on behalf of the new owners.

The day the Baseball Club of Seattle assumed control of the franchise – July 1, 1992 — Sarkowsky was not present to bask in glory in front of the news cameras. Preferring to let the new owners take the bows, he was on his yacht in Panama preparing to navigate the Canal.

“One of the things that made him successful was that he was so effective behind the scenes,” said Rice. “Very few people knew or appreciated the reach and the range of Herman Sarkowsky.”

“He never did anything for the glory of being noticed,” added son Steve.

“He was the last guy in the world to blow his own horn,” said Crockett. “These days, for most guys, it’s important to them that you know their financial worth, but Herman didn’t want you to know. He just wasn’t out there. He never tried to stand out in a crowd.”

Sarkowsky once described himself as “a risk taker by nature. The greater the risk, the better I like it, really.”

That might explain why Sarkowsky was so attracted to thoroughbred racing, a passion all of his adult life.

After his first plunge with Forin Sea in 1960, Sarkowsky built an outstanding stable that came to include Phone Chatter, winner of the 1993 Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies and that year’s Eclipse Award winner; Supercilious, a multiple-stakes winning filly, and Dixie Union, a California-bred that won seven times with three seconds in 12 career starts. The trio brought Sarkowsky $838,742, $843,454 and $1,233,190 in winnings, respectively.

Even with his national success, Sarkowsky most desired to win his hometown’s major race, the Longacres Mile. He came agonizingly close in 1971 with Titular II, a horse that had a three-length lead in the stretch but, in an epic WTF moment, suddenly stopped running, apparently distracted by a starting gate towed onto the infield after the start.

But 34 years later (2005), still chasing the dream, Sarkowsky entered No Giveaway, a 60-to-1 shot, in the $250,000 Mile. The four-year-old son of He’s Tops charged from 15 lengths down in the backstretch to beat Quiet Cash in the final jump. The $122 payoff for a $2 win ticket set a record for the highest price in the 70 editions of the Northwest’s most prestigious race.

“Dad won some huge races, but that was the moment,” said Steve. “It happened in his backyard and was something he really cared about. When he won, he was beyond giddy.”

“I think it’s my parochial view,” the-then 80-year-old Sarkowsky said after the race. “This is my home, and I just think the thrill of winning and doing it with a Washington-bred made it more satisfying. I think it’s also important to the people who are involved that the horse is local and wins here. It’s great for the breeders of the state of Washington.

“You learn some great lessons in this business. One of them is to accept disappointments. I think I’ve learned that over the years very well. The highs are really high. If you can cope with the lows you can have a ball in this game and get some real satisfaction out of it. I think everybody ought to own a horse.”

“Win or lose, he was always proud that he put his stake in the ground here,” said Wright. “He was humble about his accomplishments, but also acted on his instincts. He was the personification of ‘Nothing ventured, nothing gained.’”

Sarkowsky did more than own — he once sold a yearling out of Phone Chatter for $1.3 million at Keeneland – and play the ponies. After Longacres closed in 1992, Sarkowsky, also a member of Hollywood Park’s Board of Directors (that’s a whole other story), called Crockett and suggested that he and Dee Hubbard, a Los Angeles-based investor in all things thoroughbred, build a replacement track for Longacres.

Crockett and Hubbard formed a partnership, but it didn’t last. Crockett explained, “He kind of left the scene for a short time.” But Sarkowsky persisted, again asking Crockett to build a racetrack.

“We built the track (Emerald Downs) largely because Herman asked,” said Crockett. “He suggested we build it. This was a guy to listen to, and I did. As a result of that, all these (track) people have had jobs for 20 years.”

Sarkowsky became the second-largest investor in Emerald Downs via a partnership called Northwest Racing Associates.

“A lot of people don’t know how politically strong Herman was, and he never flaunted it,” said Crockett. “Any time you wanted to do something in Olympia, he knew all those people. When we were going to build the track, I found out he had support on both sides of the aisle. Matter of fact, I never knew which side of the aisle Herman was on, but he could wade through the waters in every possible way you can imagine.”

When he died, Sarkowsky left behind wife Faye, son Steve and daughter Cathy. On his first date with Faye, in 1951, he took her to a University of Washington basketball game at Hec Edmundson Pavilion, where she obviously didn’t hold it against her future husband that she had to sit behind a support post.

“My dad was a product of luck, timing and opportunity,” said Steve. “He had the willingness to roll the dice in a big way, and he was very good at what he did. For dad, it wasn’t about the economics or the grade of the investment, but what it meant here, to his community.”

“I can tell you from experience: There aren’t that many around today like Herman,” said Crockett.

“He never got the credit or the limelight he deserved,” said von Reichbauer. “There are a lot of things we take for granted, even though we shouldn’t. Herman supported a lot of programs that wouldn’t be around now if he hadn’t stepped up. He was one of those guys who gave back as much as he got.

“I hope his greatest legacy is that he encourages others, people with proportionally even more money than he had, to get into the giving world and not just into the taking world, and become the Herman Sarkowskys of the next generation.”

—————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

13 Comments

Excellent column on the movers and shakers in Seattle sports history. Mr. Sarkowsky’s contributions have been a huge part of what sports are today in Washington. Also like what was said about Pete von Reichbauer. He takes too much heat for his one time comment criticizing the NBA. As it turns out the NBA hasn’t warranted the respect they were demanding at the time.

You may be confusing PVR with Nick Lacata. I don’t think Pete was a player in the purchases by Ackerley and Schultz, but did try to help Bennett find an arena here, however lame was the real intent.

You are correct sir, my bad. Got my players mixed up due the memory bank purge of those times (though it still seems to pop up occasionally) but still think the NBA has dropped the ball on being given any sort of support from Seattle based on their indifference since then.

Very good profile on one of the real movers and shakers in modern Seattle sports. Herm Sarkowsky made some huge contributions. Great work as always, guys.

I wouldn’t discount Slade Gorton’s importance in the existence of major league baseball here, however. I’d expect Norm Rice to pooh-pooh Slade’s role because some people see everything through the prism of partisan politics, but every once in a while you have to put down the pom-poms and get real.

I think Sarkowsky was instrumental in the assembly of the local owners; Gorton did a favor in Congress for Nintendo, and they owed him, so Yamauchi bought 55 percent of the Mariners. Seattle needed both guys.

FINALLY!!!! Some kind of mention or reference from SportspressNW to Emerald Downs and the sport of kings!!

And (it might be mentioned) the only large-scale professional sports venue in the Seattle area since Sicks Stadium that was built without taxpayers having to foot the bill. It CAN be done.

Didn’t know that.

Depends on how you look at Husky Stadium. I consider college football a pro sport in everything but name, and the remodel was private and borrowed money. I do think the taxpayers kicked in in 1920.

But I get your point.

Steve and I share a longtime interest in the sport, Longacres and Emerald Downs. It’s a question of resources and audience.

Darn fine article by the columnist on Mr Sarkowsky. Mr Sarkowsky would have been quite pleased to know that the horse count at the track this spring is way way up from previous years.

what a great read: excellent research, great anecdotes and quotes, everything. I didn’t know any of this; I really had no idea, and i’ve been watching Seattle sports for what seems like forever. thanks!

That’s the goal of Wayback Machine: Dave and Steve want you know what’s been, so you can appreciate what is.