By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

About two hours before the 8 p.m. tipoff, lines started forming in the plaza on the west side of the Seattle Coliseum (KeyArena). Within an hour, they snaked a block deep in both directions on First Avenue North. By the time the Seattle University Chieftains and Texas Western Miners took the court, more than 16,000 fans, nearly 2,000 above capacity, were already in full frenzy.

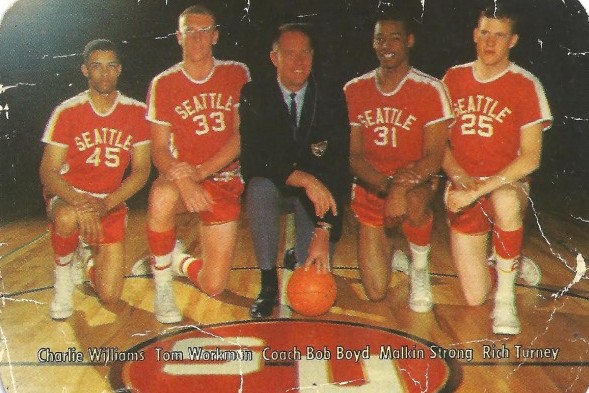

“The crowd was really big,” recalled Tom Workman, the 6-foot-7 star center of the Chieftains. “The Coliseum in those days held about 14,900 and there were actually more than 16,000 fans in there that night. The real figure was never published (at the insistence of Seattle U. athletic director Eddie O’Brien) because it was over the fire (marshal’s) limit, but there was standing room only.”

So officially, an announced throng of 11,557 swarmed the Coliseum on March 5, 1966 to watch the 15-10 Chieftains, playing under first-year head coach Lionel Purcell, close out what had been a disappointing regular season against the Miners, who reeled off 23 consecutive victories and held the nation’s No. 2 national ranking behind Adolph Rupp’s No. 1 Kentucky Wildcats, the favorite to win the NCAA championship.

Two months earlier, on Jan. 6, the Chieftains and Miners met in El Paso, the Miners winning 76-65. Despite the setback, Seattle U. players were confident they could play with coach Don Haskins’ team, especially with the crowd in their favor.

“The thing about Texas Western was that they were extremely physical,” said Workman, then in the first of two All-Coast seasons. “We matched up well with them and we were just as physical as they were. We weren’t intimidated.”

The other thing about Texas Western (now University of Texas-El Paso) that went largely unwritten until much later (and then it was written about for 50 years): Haskins sometimes – not every game, but sometimes — started an unprecedented five black players, including Houston native David “Big Daddy” Lattin and Detroit-born Bobby Joe Hill, a fact that actually failed to register as anything meaningful to Workman and his teammates, three of them black.

“That black thing meant nothing to us,” said Workman. “Most of the teams we played, with the exception of (all-white) BYU, always had players of color. I grew up in Seattle (All-State at Bishop Blanchet High School) and there were black kids in the neighborhood. That was just part of it. I didn’t give it a second thought.”

Shielded perhaps by Seattle’s ethnic diversity, Workman received his first taste of discrimination as a Seattle U. sophomore when the Chieftains played in Memphis, TN. Along with teammates Charlie Williams and Plummer Lott, both black, they walked into a restaurant only to be told they couldn’t be served because it was closing time. But it wasn’t.

“We go outside and Charlie says, ‘If you want to go in and eat, go ahead. They will serve you as long as you aren’t with us.’ I’ll never forget that. They wouldn’t serve blacks in there. That was the first time I had ever given anything like that a thought. Black, white, it didn’t make any difference to me. My idea was, strap it on and let’s go.”

According to Steve Looney, a hard-nosed Chieftain and a former multi-sport star at Roosevelt High School, the scouting report on Seattle U. was this: “We had the five most talented guys in the United States and the five biggest head cases. We didn’t always play together, but we didn’t back down from anyone. We went 16-10. We should have only lost three games.”

In their bright orange uniforms, the Miners flashed through pre-game drills like a junior Harlem Globetrotter act, Big Daddy glaring menacingly, Hill throwing behind-the-back passes, and 5-foot-6 Willie Worsley, the star of the floor show, repeatedly dunking during his turn in the layup lines.

“What bothered me most was how we had under-performed all season,” Purcell told reporters before tipoff. “We got off to a poor start. I kept looking within myself, and it bothered me when the team did not play up to its capabilities. We’ve had 10 defeats, and 10 defeats are not a very deserving recommendation.”

Although those 10 defeats eliminated Seattle U. from the 32-team NCAA Tournament field, the Chieftains took the court as if their season depended on knocking off the Miners, already scheduled to travel to Wichita two days hence for their first postseason game.

The Chieftains entered the contest bereft of the one athlete Purcell repeatedly described as the smartest basketball player he ever coached — Elzie Johnson. But Johnson hadn’t been smart enough to abide by the team’s curfew regulations. Beating Texas Western without him seemed an effort so futile as to be laughable – especially with the No. 1 national ranking at stake.

But on that night, Purcell must have been mystified as to what suddenly shot his team so full of explosive juices. Thrust by the juggled lineup into his first starting assignment as a collegian, John Wilkins provided leadership. Looney bombed the basket from middle distances. Stumpy Mike Acres spelled him with no fade in Chieftain momentum.

Malkin Strong played relentless defense, slapping down shots with the malevolence of a volleyball spiker. Jim LaCour swayed the nets with his high-arching lobs. Lott, a 6-foot-4 guard, helped disrupt the delicate balance of a Texas Western team that never suffered a defeat.

After multiple lead changes over the first 16 minutes, Seattle U. broke through Texas Western’s quick defense for the only major advantage of the first half. Looney, Workman and Lott gave Seattle a 39-36 lead with slightly more than a minute to play in the half, and then the Miners came back to trail 40-37 at intermission.

Workman led both teams with 13 points and Looney had nine. Worsley and Willie Cager each had seven for Texas Western. Williams added six and four rebounds for the Chieftains.

The Miners played with the skills of what one reporter described as “an apprentice unit of the Harlem Globetrotters.” They arrived identified as the fourth-best defensive team in the nation, but what bent the game into ultimate shape was their virtuosity: They dribbled behind the back more than necessary and took too many “circus shots,” as The Seattle Post-Intelligencer described them.

“Those shots induced roars from the gallery, but most bounced off the rim,” the P-I reported.

With 55 seconds to go, the game was close enough that a jump shot from 15 feet by Workman provided the final two of his game-high 23 points and secured the 74-72 victory. Purcell received a triumphal ride out of the Coliseum and the Chieftains made the history books.

“There are a few things about that game that stand out,” wrote Eddie Mullens, long-time Texas Western SID. “In the dressing room afterward, our players sat with their heads down and a few tears were rolling down their cheeks. Haskins said, ‘Okay, you’ve lost one game. You can go out there and win five more and win the whole thing.’

“I walked out of the Coliseum that night with two new acquaintances, the O’Brien brothers, Johnny and Eddie, who had played baseball with the Pittsburgh Pirates (and also starred for the Chieftains in basketball). On our way to my car, one of the brothers said something like, ‘You’ve lost a game tonight. But you just watch. It’ll help you win the national championship.’”

Texas Western didn’t lose again. The Miners blew through Oklahoma City 89-74, No. 7 Cincinnati 78-76, No. 4 Kansas 81-80 and Utah 85-78 before meeting No. 1 Kentucky, a team that featured future NBA head coach Pat Riley and American Basketball Association legend Louie Dampier, in the title game at the University of Maryland’s Cole Fieldhouse in Landover, MD.

The 1966 championship was hardly the stuff of what we now label March Madness. The game started at 10 p.m. Eastern, wasn’t carried live on a major TV network and was only shown on tape delay in a few American cities, including Seattle.

A grainy film shows that the crowd is white, as are the NCAA officials, the referees, the coaches, the cheerleaders, and the sports writers on press row. High in the stands, Kentucky fans brandished a Confederate flag as five white Wildcats lined up for the opening tap against Haskins’ five black players — the first time that happened in a championship game. Back in Seattle, the Chieftains gathered to watch.

“It didn’t surprise me at all that Texas Western won,” said Workman. “I remember watching that game and couldn’t believe how much Texas Western just had their way with Kentucky. Texas Western intimidated Kentucky dramatically and totally made them change their game. There was no doubt in my mind how good Texas Western was. Later, Haskins said it was a good thing that Texas Western didn’t have to play Seattle U. in the tournament.”

In fact, Haskins, asked about the Chieftains after his Miners won the championship, said, “They could just as easily have won the championship as we did.”

“The loss to us was probably the best thing that ever happened to Texas Western,” said Workman. “Coming in (to Seattle), they were overconfident and probably thought they were going to walk right through us. But they got beat, and then walked through the NCAA Tournament.”

Texas Western, which finished 28-1, received only grudging respect before playing Kentucky, and not much after beating the Wildcats. On championship weekend, Rod Hundley was quoted in The Baltimore Sun, saying of Texas Western, “They can do everything with a basketball but sign it.” After beating Kentucky, Texas Western became the first championship team in a dozen years NOT to get invited to appear on the hugely popular Ed Sullivan show on CBS TV.

At the time of Texas Western’s win, which the imperious Rupp always characterized as a fluke, none of the three major conferences in the South — Atlantic Coast, Southeastern, Southwestern – were integrated. Within two years of Texas Western’s 72-65 victory, all were.

“That one game, that one win, by an all-black Texas Western starting lineup against Kentucky for the NCAA national championship, probably did more to change college basketball than the jump shot, the three-pointer or, maybe, those short skirts of today’s cheerleaders,” said Mullens.

Forty-one years later, in 2007, the entire Texas Western team, the subject of a best-selling book and movie titled “Glory Road,” entered the Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame en masse.

“What a piece of history,” said Nolan Richardson, who became head coach at Arkansas (won an NCAA title there) after playing for Haskins at Texas Western. “If basketball ever took a turn, that was it.”

Texas Western’s place in history is secure, and not many remember its one stumble in Seattle March 5, 1966. But Seattle U.’s players, all having now reached their 70s, do.

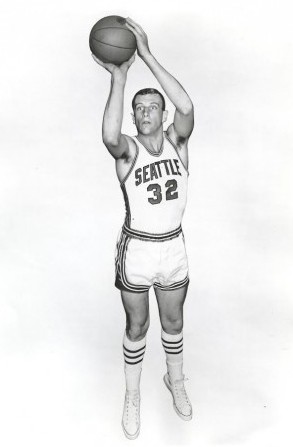

“It was a great win for us,” said Workman, who averaged 19.2 points and 8.4 rebounds during his Seattle U. career before becoming the No. 1 draft pick of the St. Louis Hawks in 1967 (played with Lenny Wilkens). “That was actually a real big win for us, to be honest.”

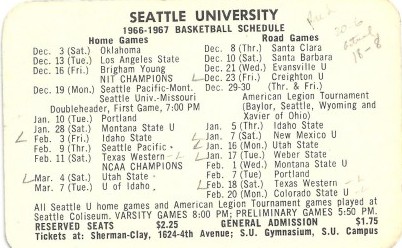

Seattle U. played defending national champion Texas Western three times the following season. As part of a home-and-home series, the Chieftains defeated the Miners 69-56 Feb. 11, 1967 and lost 80-54 in El Paso a week later on Feb. 18. The teams met again March 11 in the NCAA regionals, Texas Western winning 62-54.

In the Feb. 11 game, played in front of 14,252 at the Coliseum, Workman scored 17 points and pulled down 18 rebounds. Workman’s 13 points put the Chieftains in position to beat the Miners again March 11 in the first round of the NCAA Tournament at Fort Collins, CO., but a severe ankle sprain in the second half ended Seattle U.’s chances of advancing, as well as Workman’s college career.

“For a couple of years there, it was quite a rivalry,” said Workman. ”As far as that one game goes, again, we weren’t intimidated and had a great crowd with us. That had everything to do with our win.”

————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

7 Comments

Great write-up, guys, as always. Hard to believe now, but people actually used to care about Seattle U basketball. It’s barely an afterthought these days, even on this site, unless they’re playing the Huskies.

After the number of years SU didn’t play intercollegiate hoops, it’s taken–and will take–time for them to get back to prominence. Back then, SU and UW didn’t play–probably because UW just wasn’t much good, and SU usually was.

You also have three decades’ worth of SU as primarily a small commuter school, with students (and alumni) who were barely aware of the school’s then-NAIA athletics … and didn’t really care. (I remember a student suggesting the school dump all sports, and using the cost savings to lower tuition.) I know SU’s trying to transition into a residential campus, my nephew is considering going there, but it will take time to develop a student body that gives it more than a passing glance, and a larger share of alums who like sports.

The main reason why SU returned to D-1, after years of considering big-time sports incompatible with college education, is Gonzaga. If a similar-sized Jesuit school can explode in profile — and enrollment applications — thanks to basketball, and seemingly not sacrifice scholastic standards, why not try it themselves?

Hey, good luck to SU and any other school that wants to swim with the sharks (and in D1, it’s the sharks who win), but I’m at the point where I’d prefer to watch sports at DIII schools like UPS or PLU because I’ll be watching players who’ll be in class Monday morning, write their own papers and graduate in four years because that’s why they’re there.

I suppose idealism is reserved for anachronistic losers in 2015, but I’ll learn to live with it.

Charlie Williams’ final year was 1965. So, who was the Williams who scored six points and had four rebounds?

Awesome column, All these names are legends in Seattle basketball. Even remember when Buckwalter was with the Sonics.

Bucky deserved better from the Sonics than he got. He went on to be an NBA pioneer in scouting and signing Europeans and a key player in Moses Malone turning pro with the Utah Stars (VERY controversial at the time but Modine is safely ensconced in Springfield now). Maybe Phil Knight can buy his way into Springfield, but Bucky has a legitimate claim to be a HOFer…he’s been a true visionary as opposed to selling a bunch of overpriced shoes.