To help explain the role the football team played in the remarkable series of events over the weekend that resulted in the ouster of the University of Missouri’s president and chancellor, we turn to one of the great sages of American higher education.

Prof. Quincy Adams Wagstaff: ”The trouble is, we’re neglecting football for education.”

Fellow professors: ”Exactly, the professor is right.”

”Where would this college be without football? Have we got a stadium?”

”Yes.”

”Have we got a college?”

”Yes.”

”Well, we can’t support both. Tomorrow we start tearing down the college.”

Wagstaff wasn’t in the athletic department at Missouri. In fact, he was Groucho Marx. The dialogue was part of Horse Feathers, a Marx Brothers film that skewered hilariously the place of big-time football on campus.

In 1932.

In the intervening 83 years, little has changed in the fundamental relationship between the tail of football wagging the dog of big colleges. The Missouri football team helped tear down part of the college.

From the outside, it seemed a worthy endeavor, given president Tim Wolfe’s inept, tone-deaf response to a string of racially hostile episodes on campus.

However, amazement over the irony that it took the threat by the football team to boycott its job to achieve a broader campus goal — throttling racial discrimination — is misplaced. As Groucho pointed out, that kind of influence has always been there. It’s a plain fact of American educational life. To suggest irony is to imply willful ignorance of the truth.

What is rare: For student activism to percolate into the athletics empire. Why? The perceived risks are too great for nearly all scholarship athletes.

Here’s the real irony in the Mizzou story: If the football team used the same tactic in an attempt to right a grievous wrong within the program — an abusive coach, discrimination, compensation, length of practices, etc. — it likely would go nowhere.

Only in big-time football and men’s basketball, the sports that generate the billion-dollar revenues that sustain the “amateur” colossus of big-time sports, is there near-absolute authority of program over people. The coach is a benevolent dictator who governs all (except when it’s not convenient: See Pitino, Rick, and Louisville brothel), especially including what athletes usually believe is the key to their futures: An endorsement from the coach to pro scouts.

Most scholarship athletes are in colleges strictly on their athletic prowess, which 95 percent believe will lead to pro sports careers. About 95 percent of that cohort is wrong, but it is that mythology that coaches use to help maintain relative order.

As a recent illustration, CB Marcus Peters took pains to publicly accept full responsibility for a series of misbehaviors that got him thrown off the Huskies football team last season by coach Chris Petersen. Peters would certainly have been draftable regardless, but he recognized the value of a re-embrace by Petersen in advancing his draft stock.

He was taken 18th in the first round by Kansas City, where he has started all season.

A more distant UW example happened under coach Don James, who in 1986 experienced a mini-rebellion by some players who didn’t want to accept an invitation to the Sun Bowl, saying the minor bowl wasn’t worth the time and trouble around Christmas. James responded by saying he would call NFL scouts to inform them of each player’s decision. Protest over.

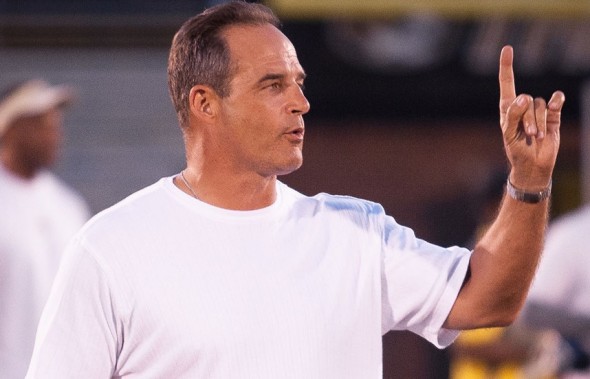

James’ offensive coordinator at the time was Gary Pinkel, now the head coach at Missouri. At first glance, it would seem that Pinkel’s endorsement of players’ threat to boycott runs counter to the presumed position of James, whom Pinkel hailed upon his death in 2013 as “my coach, my mentor, my friend (who had) such an amazing influence on my life, both personally and professionally . . . the program we built at Missouri is Don James’ program. It’s a tribute to how he developed men and built football teams.”

Pinkel drew praise for supporting his players. But in this case, what choice did he have? Oppose them on a non-football issue of race, and be unable to recruit African-Americans?

Pinkel’s job is to win football games, and he’s done it well — the winningest coach in Tigers’ history, he was 12-2 and 11-3 the past two years in the brutal Southeastern Conference before the 4-5 mark this season. Almost by definition, Pinkel could be no supporter of the boycott. But he was too far behind it.

When the maelstrom suddenly boiled up and reached his desk, he had no choice but to say, more or less, “Um . . . me too.”

This is how he actually said it Monday at a press conference after Wolfe’s stunning resignation:

“I became involved because I support my players,” he said. “I did the right thing, and I would do it again.

“On Saturday and Sunday, it was not about football.”

The key point was Saturday and Sunday. By Monday, Pinkel and the school faced a loss of about $1 million if the boycott forced a forfeiture of the Saturday game against BYU. But Wolfe’s resignation saved money, controversy and probably a split in the program by some players who privately may not have believed the sacrifice of a game was worth it.

Some observers have hailed the Missouri activism as a breakthrough in the social-issues silence that smothers most students in big-time college sports. Perhaps.

But the Missouri circumstances were unusual, and had nothing to do with the conduct of the football program, meaning the protest and threatened boycott were beyond the reach of the NCAA’s onerous rulebook and each school’s code of athletics behavior.

It’s doubtful we’ll see a movement of big-time college teams jeopardizing their futures by posing prostrate in front of the doors of the admin building. The risk of loss of revenues, real and imagined, is too great. But at least the idea of the threat, now equipped with a paradigm, may prove handy.

If only the jocks would apply the pressure on their own sports programs, they wouldn’t have to wait for years of successful litigation to get their fair share of the millions in TV revenues made off their free labors.

Somewhere, somehow, someone needs to prove Groucho had it backward.

10 Comments

Any day that begins with a Groucho joke is another day worth living. He unfortunately did not have it backward regarding football or education, or regarding this:

Prof. Wagstaff: Why don’t you go home to your wife? I’ll tell you what, I’ll go home to your wife, and outside of the improvement she’ll never know the difference.

Made my day, X. One of the great wits of the 20th century.

moment of silence for armistice day in 2 minutes at 11:11 am sportspressnwesterners. peace

To you too.

From the outside, it seemed a worthy endeavor, given president Tim

Wolfe’s inept, tone-deaf response to a string of racially hostile

episodes on campus.

Episodes that haven’t even remotely been proven to have actually happened.

So everyone is making up stuff, right?

It comes down to how one envisions the purpose of a university. In my opinion, when institutions of higher learning are able to focus efforts on preparing and placing into society doctors who can cure disease, biochemists who can create medicines, archaeologists who can dig up our history, astronomers who can discover the universe, engineers who can build things, and etc. . . . Sorry, but the ability to play football is wwaaayyyy down on the list.

I think you might get unanimity on that one, Mr. PM. But the point was that the entertainment division too often runs the university.

black football players have a history of effecting social change: http://www.wyohistory.org/essays/black-14-race-politics-religion-and-wyoming-football