By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Editor’s note: The potential arrival of a National Hockey League franchise in 2020 in a remade Seattle Center arena has prompted Sportspress Northwest to present a six-part series revisiting the sport’s Seattle history from previously published Wayback Machine stories. Part 3 next Wednesday: Hockey icon Pete Muldoon, who could skate on 26-inch stilts.

In the tortured history of major league sports in these parts, mainly a dense catalog of soaring mediocrity, no team ever came closer to achieving dynasty status than the 1917-20 Seattle Metropolitans of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (1911-24). Boasting three future Hall of Fame players (and, in hindsight, putting all future Seattle franchises to shame), the Metropolitans battled for the Stanley Cup three times in a four-year span.

Winners once and vexed twice, the Metropolitans and their barber pole uniforms now amount to a quaint curiosity at best, an insignificant relic at worst. But had the Metropolitans not simultaneously collided with the vile side of Mother Nature and a U.S. military snafu, history might have a different story to tell.

The Patrick brothers, Frank and Lester, formed the PCHA in 1911 after locating in British Columbia to assist in the family lumber business. After establishing franchises in Vancouver (Millionaires), Victoria (Senators) and New Westminster (Royals), B.C., the Patricks launched an aggressive campaign of expansion. The Metropolitans became a product of that growing commerce, squalling into existence for the 1915-16 season.

When the Mets made their debut, the PCHA had forged a considerable reputation for innovation. It introduced the blue line and goal crease, the forward pass and penalty shot, none yet adopted by the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the National Hockey League).

The PCHA also became the first league to implement a farm system, the first to feature numbers on players’ sweaters, and the first to hold playoffs (Frank Patrick is given most of the credit for the innovations). The PCHA eliminated a rule that mandated goalies must stay on their feet, and it played seven men to a side vs. the NHA’s six.

The clear quality of hockey in the PCHA convinced the more established NHA to permit its regular-season champion to challenge the PCHA’s best for possession of Lord Stanley’s Cup. In 1916-17, the Metropolitans became that challenger, and made the most of their chance.

In a five-game series conducted in front of packed throngs at the Seattle Ice Arena, the Metropolitans obliterated the more famous Les Canadiens by an aggregate of 19 goals to three, becoming the first American team to hoist Stanley’s Cup, and the first Seattle franchise to win a major pro title in any sport.

Two years later, the Metropolitans again qualified to vie for the Cup, and once more their rival was Montreal. A different outcome here would have defined the Metropolitans in a far more favorable historical context had it not been for two external developments: The 1918-19 worldwide Spanish influenza pandemic, and the odd misfortune that befell Bernard Patrick Morris, Seattle’s leading scorer.

Medical researchers traced the Spanish influenza outbreak in the U.S. to March 18, 1918, a year before the Metropolitans and Canadiens met for the second time. An unidentified Army private at Fort Riley, KA., reported to the camp hospital complaining of a fever, sore throat and headache. Before the day ended, more than 100 Fort Riley soldiers had taken ill.

From Fort Riley, the flu hop-scotched to Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago and Baltimore, its spread coinciding with massive movements of military personnel, and high concentrations of populations, during World War I (Seattle’s population swelled to 400,000, largely due to military and shipbuilding needs). By the time the influenza reached Seattle Oct. 3, 1918, some 21 million had died globally, including 700,000 in the U.S.

On Oct. 5, 1918, Seattle Health Commissioner Dr. J. S. McBride stated that influenza is “admittedly prevalent in the city” and blamed its presence on a trainload of sick draftees from Philadelphia bound for the University of Washington Naval Training Station. Soon, Seattle health officials recorded 700 flu cases and one death, despite taking rapid action.

They issued an order on Oct. 29, 1918, making it mandatory that all city residents wear six-ply gauze masks. The state followed with a similar order the next day, covering everyone living outside the King County limits.

To keep the flu in check, authorities forced an end to mass gatherings until the crisis passed, banning dances and theater attendance, closing schools, and curtailing streetcar service. While the city busied itself with major road cleanings and garbage removal, its politicians passed an anti-spitting law.

The city insisted that only close relatives of a deceased could attend his/her funeral, and that no religious services would be permitted for at least two weeks following initial manifestation of the flu. When ministers whined, Mayor Ole Hanson (later famous for founding the city of San Clemente, CA.) remarked, “Religion which won’t keep for two weeks is not worth having.”

Local sport did not go untouched. Because of the manpower drain caused by World War I, plus the added complication of the flu, the University of Washington football team played only two games in 1918, one against Oregon, the other against Oregon State (helping fight the war in Europe, head coach Claude Hunt missed both games).

The UW managed a 16-game basketball season, but no games were played in the late fall after the flu erupted. The season started Jan. 17, after the flu seemed to have abated, and included limited travel: Of the 16 games, UW played four against Washington State, four against Oregon, and four against Oregon State.

Because the disease appeared in Seattle six weeks after it first struck eastern U.S. cities, Seattle officials had a chance to plan for its arrival. The Department of Health and Sanitation, in conjunction with doctors at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, developed a vaccine and ordered that all shipyard workers be vaccinated. Of the 10,000 vaccinated, none developed influenza.

But Seattle had more than 10,000 citizens. After Armistice Day on Nov. 11, 1918 marked the end of World War I, thousands celebrated in Seattle’s streets, sans gauze masks. The city lifted the mask rule the next day and re-opened theaters and other public places. Sure enough, the flu began another rampage before dropping off again. Schools did not re-open until mid-January, 1919.

By March, about 1,600 in Seattle succumbed to the flu. But the city had been relatively fortunate. Seattle suffered a death rate half that of San Francisco and a third of that of Baltimore and Philadelphia.

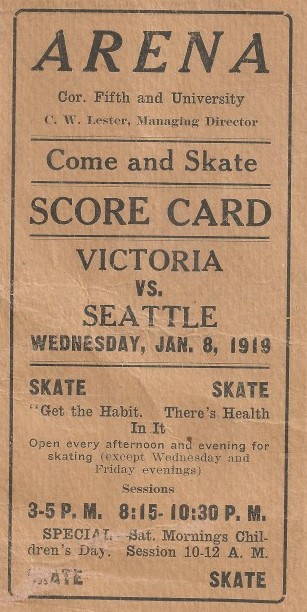

Oddly, the flu bug never reached Fifth Avenue in downtown Seattle, especially between Seneca and University streets, where the Metropolitans played their entire regular season at the Ice Arena without a reported health-related incident, They finished 11-9, good for second place in the PCHA standings, a game behind the Vancouver Millionaires.

According to PCHA rules, its top two regular-season teams would face off in a two-game, total-goals series, the winner earning the right to challenge the NHA champion for the Stanley Cup. Game 1 would be held in Seattle, Game 2 in Vancouver.

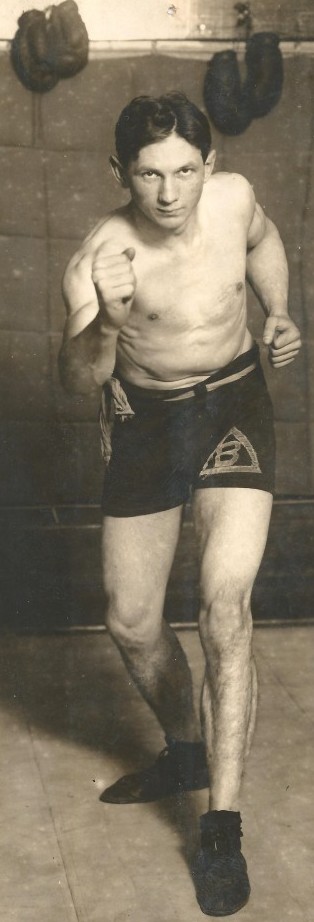

Moments before the start of Game 1 on March 13, Metropolitans coach Pete Muldoon, an off-season boxer and lacrosse player and later famous for hexing the Chicago Blackhawks with the infamous “Curse of Muldoon,” received a telegram from star goal scorer Bernie Morris.

Muldoon gathered his Mets and read it to them. It said, with no elaboration, ”Fight like ———- tonight and win!”

The public clueless, Muldoon and his players knew exactly why Morris had gone MIA. A week earlier, following the final game of the regular season, a 3-1 Seattle win over the Victoria Aristocrats (nee Senators), he had been arrested and charged with draft evasion and desertion in a time of war. When Morris did not appear at the Ice Arena for the first game against the Millionaires, many Seattle fans suspected he had come down with the flu.

A Canadian who worked legally in the U.S., Morris registered for the draft with the Canadian and U.S. militaries for World War I. He received exemptions from both countries from service, but when the Americans entered the war in April 1917, Morris’s status changed. Slightly more than a year later, authorities sent Morris a draft notice to his off-season home in Vancouver, B.C. Morris never received it (his testimony). He was off playing hockey.

When Morris did not respond to his draft notice, officials declared him a deserter (Oct. 13, 1918). It took Morris another four months to discover he was in hot water. When he did, he hastily reported to Camp Lewis (now Joint Base Lewis McChord), figuring there had been a misunderstanding, and that he would be able to sort things out.

Draft Board No. 6 grilled Morris for several hours, then released him. But board chairman W.M. Whitney soon thought the better of it and revoked Morris’ release, saying that a notorious character such as Morris could not be allowed to roam the streets. Morris again voluntarily turned himself in, and no one would see him again for more than a year.

“Bernie left behind a disconsolate bunch of stick handlers on the very night of their most important game,” the Seattle Times reported.

Inspired by Morris telegram, the Metropolitans routed the Millionaires 6-1 in Game 1. Frank Foyston produced a hat trick. The Metropolitans lost Game 2, 4-1, but earned the right to face Montreal for the Stanley Cup on the basis of aggregate goals (7 to 5).

With Morris still under lock and key at Camp Lewis, the Metropolitans would have to play for the Stanley Cup without their leading scorer, one reason why newspapers favored the Canadiens. Another: the big names in the Montreal lineup.

Five of its players would one day enter the Hockey Hall of Fame: left wing Joe Malone (1950), player/coach Newsy Lalonde (1950), defenseman Bad Joe Hall (1961), right wing Didier Pitre (1962) and Georges Vezina (1975), the man after whom the Vezina Trophy, awarded annually to hockey’s top goalkeeper, is named.

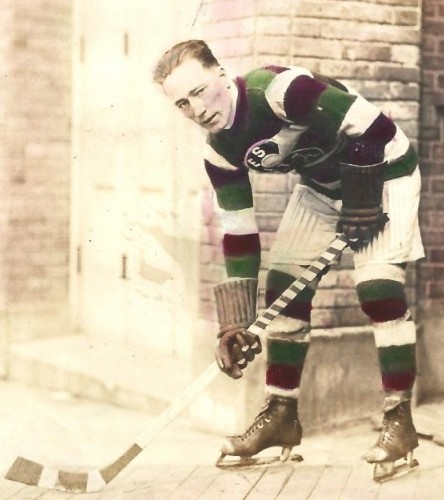

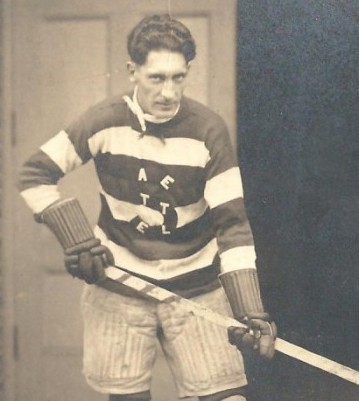

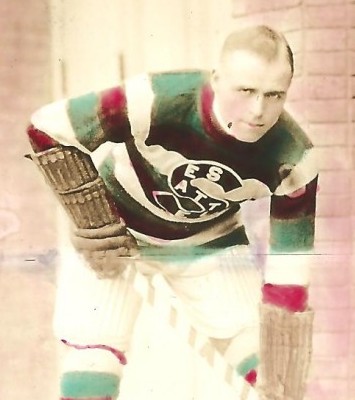

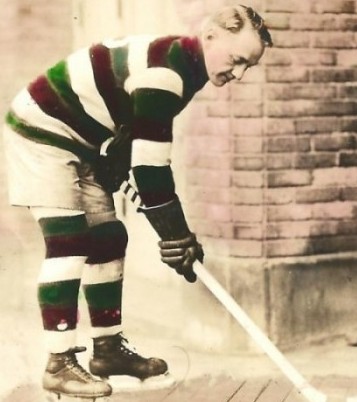

While Montreal had a 5-3 lead on the Metropolitans on the future Hall of Fame list, Seattle didn’t lack for talent. Foyston, perhaps the club’s best overall player, defenseman Jack Walker (credited with introducing the hook check to hockey) and goalie Hap Holmes, would enter the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1958, 1960 and 1975, respectively (during the off-season, Foyston and Holmes jointly owned and operated a 2,800-acre wheat and cattle ranch in Canada).

As a counter to Montreal’s Bad Joe Hall, the Metropolitans trotted out the PCHA’s top enforcer, Cully Wilson, an off-season shipyard worker who had established his bona fides in the goonery niche by breaking the jaw of Mickey MacKay (Vancouver Millionaires) in a fight by using his stick to cross-check MacKay in the face.

But with Morris missing, the Metropolitans had no real answer for Lalonde, Montreal’s captain and top scorer. Two years earlier, Morris tallied a staggering 14 goals against the Canadiens in Seattle’s four-game triumph, including six in the 9-1 Stanley Cup clincher. He scored 20 goals with 22 assists in the 1918-19 PCHA season, one shy of the league-leading 23 tallied by Cyclone Taylor of the Vancouver Millionaires. He was Seattle’s leading scorer for four consecutive seasons, and a four-time All-Star.

The Metropolitans had two advantages: The best-of-five series would be played entirely in Seattle (the finals alternated between east to west); and PCHA rules would be in force for Games 1, 3 and 5 (the PCHA played seven men to a side while NHA played six to a side).

The 1919 series began in Seattle on March 19, the Metropolitans dominating, 7-0. Foyston contributed a hat trick and Muzz Murray had two goals, but the star of the evening was Holmes, who repelled shot after shot, clearly outplaying Vezina.

Game 2 went off three days later. That morning, after W.M. Whitney, chairman of Draft Board No. 6, testified that Morris had deserted his adopted country, or at least the country in which he made his living, Judge E.E. Cushman denied Morris his release. A courrt date was set for mid-April, after which the attorney for Morris, Albert Moodie of Seattle, threatened to take the case to President Woodrow Wilson.

That night, in a game played under Eastern rules – six men to a side — Montreal won 4-2 as Lalonde set a Stanley Cup record by peppering four pucks past Holmes. A melee nearly erupted when Wilson deliberately slapped a puck into the nose of Hall, but the thrust of post-game reporting had as much to do with local scribes bemoaning the absence of Morris as it did the game action itself.

The teams reverted to Western rules for Game 3. Seattle won 7-2, Holmes returning to form and Foyston scoring two unassisted goals with an assist. Had the Metropolitans offset Malone’s four goals with any from the prolific Morris in Game 2, this 7-2 victory would have given Seattle its second Stanley Cup in three years.

Game 4 might have been the greatest ever on the West Coast, at least according to on-the-spot post-match opines. Regulation ended 0-0, and stayed that way following 20 minutes of wild overtime, in which both Holmes and Vezina blocked every shot. Louis Berlinguette of Montreal had a chance to win it in OT, but missed by inches.

Montreal took Game 5, 4-3, to level the series at 2-2-1 and force a decisive, and previously unscheduled, Game 6. Seattle sports writers again made specific mention of Morris’s absence, and what his shotmaking might have provided the Metropolitans.

Five and a half hours before the Game 6 face-off, players on both teams suddenly took ill with the flu. Health officials quickly dispatched five Montreal players to local hospitals, and ordered the rest of the Canadiens to remain in their rooms at the Georgian Hotel. Jack McDonald became the first Canadien to go down, followed by Lalonde, Hall, Billy Coutu, Berlinguet and team manager George Kennedy. All had fevers ranging from 101 to 105 degrees.

From his hospital bed, Kennedy announced he would forfeit the Cup to Seattle, but Muldoon refused to accept, recognizing that catastrophic illness had caused the Canadiens to be short of players.

Kennedy asked if he could borrow players from the Victoria Aristocrats of the PCHA, but league president Frank Patrick scotched the idea. Several Victoria players had been ravaged by the flu, and some suspected the Canadiens picked it up from Victoria players when they stopped there for an exhibition game prior to arriving in Seattle.

With Patrick having no other alternative, and Seattle public health officials fearful of a large flu outbreak if 4,000 fans jammed the Ice Arena for Game 6, the contest was called off.

The 1919 Stanley Cup playoffs ended with no champion, marking one of only two times the trophy was not awarded (2004-05 season was wiped out due to a labor dispute). That season is recorded on the Stanley Cup today simply as: ”1919, Montreal Canadiens, Seattle Metropolitans, Series Not Completed.”

On April 5, Bad Joe Hall died at Seattle City Hospital from pneumonia that developed while he battled the flu. Many of his teammates attended his funeral in Vancouver April 8.

The other Montreal players eventually recovered, but a weakened Kennedy never did. He suffered from ill health for two years and died at 39 in 1921, most attributing his early demise to the lingering effects of Spanish influenza. Two months later, Kennedy’s widow, unable to meet the team’s financial obligations, sold the Canadiens for $11,000.

Two weeks after Seattle health officials nixed Game 6, a Camp Lewis jury convicted Bernard Patrick Morris of desertion from the U.S. Army in a general court martial. A judge sentenced him April 13 to serve two years of hard labor at Alcatraz.

No one today knows if Morris served his sentence there: Alcatraz did not keep inmate records prior to 1934. Today, the general belief is that Morris remained incarcerated at Camp Lewis, as the case against him grew increasingly weak.

Following a year of questioning and investigations, the military dropped all charges against Morris, no explanation forthcoming. The military permitted Morris to return to hockey, but by then he had missed the 1919 Stanley Cup finals, the entire 1919-20 PCHA regular season, and the PCHA playoffs.

Morris departed Camp Lewis just in time to accompany the Metropolitans to Ottawa for the 1920 Stanley Cup finals against the Senators. But having spent so much time in detention, Morris couldn’t get his hockey legs under him. Out of shape, he managed just two assists in five games as the Metropolitans lost the series three games to two. Morris had 27 points in his previous 17 playoff games. An in-shape Morris might have swung the Cup toward Seattle.

Those who witnessed the 1919 Stanley Cup finals wrote floridly — and convincingly — that Seattle could – and probably would – have won at least one of the two games the Metropolitans dropped had Morris been available.

Arguing against that: NHA rules were used in Mets’ losses, and Seattle might have lost both even with Morris (both the Canadiens and Mets had their usual style of play disrupted by NHA and PCHA rule differences).

Or maybe not. With Morris, the Metropolitans might have swept the Canadiens in the first three games of the 1919 series. Seattle outscored Montreal 16-6 in those engagements, making Game 6, and the tragedy that engulfed it, unnecessary.

Morris rejoined the Metropolitans for the 1920-21 season and spent three more years with the club before it traded him to Calgary. The Mets never again challenged for the Stanley Cup, nor enjoyed the local popularity they had from 1917-20. By 1924, the Mets (and the PCHA) had become awash in financial problems. Attendance plummeted to fewer than 1,000 per game.

The PCHA folded the Metropolitans in the summer of 1924, dispersing its players into the newly formed Western Canada Hockey League. The Seattle Ice Arena briefly became a public roller-skating rink, and then was converted into a parking garage.

Bernie Morris played hockey through the 1929-30 season, closing out his career with the Hamilton Tigers, following a six-game stint with the NHL’s Boston Bruins. When he died in May 1963, cause of death unknown, exact date unknown, no local newspaper published his obituary.

The Metropolitans pose for a team shot at the downtown Ice Arena. Bernie Morris is third from left. / David Eskenazi Collection