By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Editor’s note: The potential arrival of a National Hockey League franchise in 2020 in a renovated Seattle Center arena has prompted Sportspress Northwest to present a six-part series revisiting the sport’s Seattle history from previously published Wayback Machine stories. Part 4 next Wednesday: Golden Guyle Fielder and the Seattle Totems.

For most Puget Sound-area sports fans today, the primary winter sports passion has been basketball, despite the loss in 2008 of the SuperSonics to Oklahoma City. But if Oak View Group’s renovation plan works for a premier arena at Seattle Center, the opportunity presents itself for the city to revert to its sporting self-image in several decades prior to the NBA: A hockey town.

Since the Western Hockey League Seattle Totems vanished in the late 1970s, leaving a trail of lawsuits in their wake, only junior hockey has slaked the thirst of local hockey mavens.

For decades, Seattle viewed itself as more of a hockey town than a basketball burg. Its first major figure in the ice game is actually more famous for something he didn’t do, rather than for the myriad of remarkable things he did.

Born in 1881 (exact date unknown) in St. Mary’s, Ontario, Linton Muldoon Treacy grew up mainly playing hockey and lacrosse. When, in 1909, it was time for Treacy to make a living, he moved to the Northwest to pursue a career not as a hockey or lacrosse player, but as a professional boxer.

In those days, professional athletes were widely viewed as loathsome lowlife. So out of respect for his family, Treacy shed his given name and assumed the alias Pete Muldoon.

Initially a middleweight (later a heavyweight), Pete Muldoon joined the Ballard Athletic Club, which presented weekly boxing cards, and showed immediate promise. After a few matches, the Seattle Times wrote, “Pete is a clever boxer and has a stiff punch. The striking feature of this boxing Muldoon is his excellent judgment and ability to get away from punishment. He has been in the ring with several good boxers, but none was able to lay a glove on him whenever said glove was backed up by any considerable force.”

Muldoon’s complete boxing record hasn’t survived, but parts remain. According to Boxrec.com, Muldoon engaged in his first notable bout July 1, 1910, winning on points at the Snohomish Stag Club against Stockton, CA., puncher Ed Reilly (Muldoon issued such a beating that Reilly never fought again).

Muldoon had only four more fisticuffs of consequence. He recorded a third-round TKO over Bob Armstrong, who outweighed him by 40 pounds, at the Ballard Athletic Club Dec. 21, 1910, and lost by TKO in three rounds to Cle Elum’s Jack Lester Jan. 17, 1911, at the Dreamland Rink in Tacoma, when Muldoon’s handlers threw in the sponge.

Muldoon’s final ring endeavors ended in draws, against Lee Manson (Dec. 15, 1911) and Vancouver’s Billy Weeks (March 28, 1913).

Muldoon never boxed on a full-time basis, fight-game money insufficient for his financial needs. So near the end of his career, in 1912, Muldoon left Ballard for Vancouver to manage what one newspaper called Canada’s crack lacrosse team (lacrosse was a pro game in Canada), and train its hockey (Millionaires) and baseball (Beavers) teams. When he found time, Muldoon moonlighted as a boxing referee.

Earlier in his boxing career, Muldoon met up with brothers Frank and Lester Patrick, who in 1912 offered him an opportunity to supplement his income by playing for the Vancouver Millionaires of the new Pacific Coast Hockey Association they had formed. Muldoon agreed, making him simultaneously a professional fighter and hockey player.

Montreal natives, the Patricks relocated to Nelson, B.C., to work in the family’s lumber business. When their father, Joe, sold the mill in 1911, Frank and Lester took their profits and invested in hockey franchises.

They launched the PCHA in 1912 with three clubs, the Millionaires, Victoria Senators and New Westminster Royals. The Patricks, who owned the franchises, stocked the teams by conducting systematic raids on the NHL’s forerunner, the National Hockey Association.

Despite the PCHAs blatant poaching of NHA players, the NHA agreed in 1912, to send a collection of its best players to the West Coast to play a PCHA All-Star team in a pair of games some newspapers described as the World Series of hockey.

The PCHA won both contests, 10-4 and 5-1, demonstrating to the more established NHA that the caliber of PCHA play was at least as good as its own, if not better. So in 1913-14, the NHA struck a cooperative agreement with the PCHA, mainly to stem the tide of player jumping.

This led to a further agreement: The regular-season champions of each league would face each other in a special, postseason challenge series. Following the 1914 season, PCHA winner Victoria went east to play the Toronto Blueshirts.

Won by Toronto, that competition shaped a further NHA-PCHA agreement: the leagues would engage in an annual playoff to determine the winner of the Stanley Cup, which had been awarded since 1893.

The first PCHA-NHA Stanley Cup took place following the 1914-15 season. The Millionaires beat the Ottawa Senators in a best-of-five series.

The Patricks had trouble keeping their franchises in the black. When they could not make a go of the New Westminster Royals, afflicted by poor attendance and a shabby arena, they shifted the club to Portland and sought out Muldoon to run the Rosebuds on their behalf.

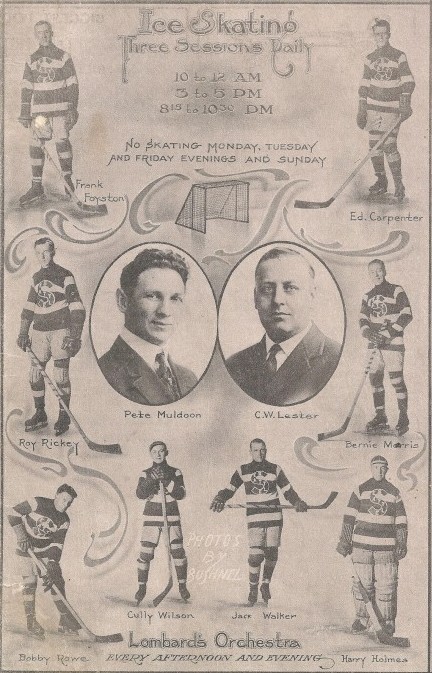

A year later (1915), the Patricks created a new PCHA team, the Metropolitans (see Wayback Machine: Frank Foyston and the Metropolitans), and asked Muldoon to leave Portland for Seattle, which just finished construction of a new ice arena on Fifth Avenue between Seneca and University streets. Muldoon agreed, setting up one of the seminal careers in the history of professional hockey in Seattle.

“Pete Muldoon will be manager of Seattle’s hockey team,” announced The Times. “Pete handled the Portland team last year and made a splendid showing. While rumors were printed that Pete would be transferred to Seattle, it was not until today (Oct. 15, 1915) that he got his release from President Savage of the Portland club.

“He will at once begin hustling for players, for both he and the Patrick boys know that Seattle must have a strong team in order to make hockey go here in its first season. Muldoon is well known and popular in Seattle, and his selection is a good one. He is a splendid skater himself, but seldom plays hockey any more, though he can give a good account of himself in a pinch.”

Actually, Muldoon was more than a splendid skater, as The Times explained in a story midway through his tenure with the Metropolitans.

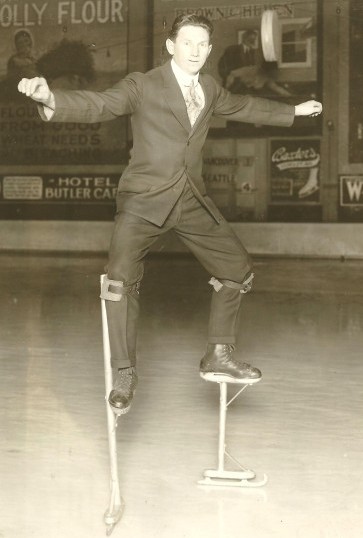

”Before Pete Muldoon, manager of the Seattle hockey team, learned his multiplication tables,” the story said, “he was doing stunts on skates that were the envy of his school mates. Pete has forgotten his multiplication tables now, but he still can cavort on ice as few skaters in the world are able to.

“When he is not bossing the Seattle puck chasers, Muldoon puts in his time doing exhibition skating in rinks in all parts of the United States. Some of his favorite and most difficult stunts are performed on stilt skates, which raise his feet 26 inches above the surface of the ice.

“Norman Baptie, world’s champion speed skater, and Johnny Davidson, who is now giving skating exhibitions in London, are the only two other men in the world who perform on ice stilts. These men use 18-inch stilts. Muldoon uses stilts eight inches higher and makes these exhibitions a regular part of his repertoire.”

The Times quoted Muldoon: ”With practice, a man can do anything on stilts that he can do on regular skates. All it takes is nerve.”

Muldoon not only gave stilt-skate exhibitions (he garbed himself in an Uncle Sam costume), he and a series of partners (one 13 years old) traveled the country giving ice dancing exhibitions 50 years before ice dancing became part of the Winter Olympics program (1976).

A professional showman as well as a former professional athlete, Muldoon had a lot of creative ideas for how to market the Mets (Muldoon also opened and successfully marketed a series of West Coast-based winter sporting goods stores).

To make the Mets’ Ice Arena games more entertaining, Muldoon cooked up promotions to occupy the 10-minute intervals between periods. As the Post-Intelligencer explained, “Manager Muldoon plans on filling in these rests with exhibitions of fancy skating and with speed races. Speed skating is not allowed ordinarily, but those who like to go fast will be given a chance during the intermissions. Manager Muldoon wants the entries of the boys who think they are fast and a gold medal will be hung up for the winner.”

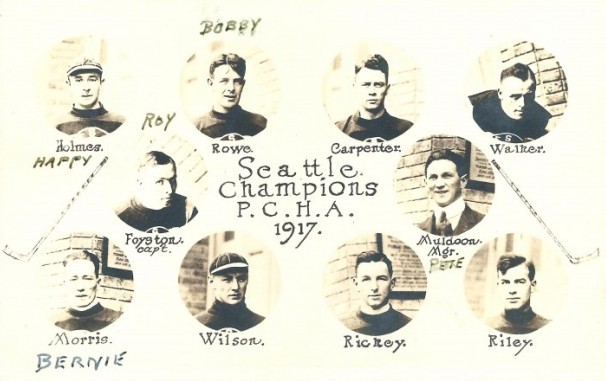

Featuring three future Hockey Hall of Famers forwards Frank Foyston and Jack Walker and goalie Harry Hap Holmes — the Mets went 9-9 in their first season (1915-16), finishing tied for second with Vancouver. As seattlehockey.net opined in its excellent history of hockey in the city, “The people of Seattle had taken to hockey.”

By defeating Portland on the road in the final game of the 1916-17 season, the Mets won the PCHA title with a 16-8 record, earning the right to host the Montreal Canadiens for the Stanley Cup.

In the subsequent four-game series conducted in front of packed throngs at the Seattle Ice Arena, the Metropolitans obliterated the more famous Les Canadiens by an aggregate of 19 goals to three, Bernie Morris scoring 14 of them. That made the Mets the first American team to hoist Stanley’s Cup, and the first Seattle-based franchise to win a major pro title in any sport. Muldoon was 30, making the youngest to coach a Stanley Cup champion (he’s still the youngest).

Muldoon is commonly listed as having coached the Mets for the duration of their existence (1915-24). In fact, he did not. A few months after the Stanley Cup clincher, Lester Patrick decided to fold his one-year-old Spokane franchise, the Canaries, who had moved to eastern Washington from Victoria following the 1915-16 season.

As co-owner of the PCHA, Patrick could work with any franchise he desired, and in 1917-18, he decided to become player-manager of the Metropolitans and send Muldoon back to his old job as manager of the Rosebuds.

Under Patrick, the Mets missed a chance for the Stanley Cup again when they lost a two-game playoff series with Vancouver.

For the 1918-19 season, Patrick removed himself from Seattle, joined the Victoria Aristocrats, and ordered Muldoon back to Seattle. By year’s end, Muldoon had the Mets playing for the Stanley Cup again, once more against Montreal.

This became the most unusual – and tragic — Stanley Cup series ever contested. Seattle and Montreal split the first two games, and after five the series stood 2-2-1.

Five and a half hours before the Game 6 face-off, players on both sides suddenly took ill with the flu (the worldwide Spanish influenza epidemic had just about, but not entirely, run its course). Health officials quickly dispatched five Montreal players to local hospitals, and ordered the rest of the Canadiens to remain in their rooms at the Georgian Hotel.

Montreal manager George Kennedy, who had been hospitalized, announced from his bed that the Canadiens would forfeit the Cup to Seattle, but Muldoon refused to accept, recognizing that catastrophic illness had caused the Canadiens to be short of players.

So the series was canceled and no Stanley Cup was awarded (see Wayback Machine: How The Mets Missed A Dynasty).

The Mets played for the Stanley Cup again in 1920, but lost to the Ottawa Senators, and had two more shots at the Stanley Cup in 1921 and 1922, but were eliminated by Vancouver in the PCHA playoffs both years.

Two years later, the PCHA folded, the Mets disbanded, and the Western Canada Hockey League, featuring edition No. 2 of the Portland Rosebuds (the former Regina Capitals), came into existence. Muldoon, who posted a record of 115 wins, 105 losses and four ties in Seattle, became the coach.

But the WCHL didn’t last, either. Frank Patrick negotiated the sale of Muldoon and most of the Rosebuds players to a Chicago investor who was forming an expansion franchise (then called the Black Hawks, now the Blackhawks) in the National Hockey League, which had evolved out of the National Hockey Association following the 1917 season.

The investor, Major Frederic McLaughlin, also the club president, thought the Black Hawks should have won the league’s American Division in the team’s first year (1926-27), and blamed Muldoon for finishing third (19-22-3). Chicago’s third-place finish would have quickly faded into history, but instead evolved into a charming fable that supposedly explained why the Black Hawks/Blackhawks never finished first from 1927 until 1967, when the team finally won its first regular-season title.

Two weeks before the end of the 1926-27 season, Muldoon resigned, giving 14 days notice. He could not stand McLaughlin’s meddling.

“Our worthy president wanted to run the club, the players, the referees, etc.,” Muldoon said a few weeks after his departure. “He learned the game very quickly. In fact, after seeing his first game, he wrote me a letter telling me what players should and should not do.”

This is how Muldoon became famous for something he had no part of: Two decades after Muldoon left Chicago, the Blackhawks’ publicist, Joe Farrell, who doubled as the radio play-by-play broadcaster, concocted a story designed to make the hockey club lovable losers just like baseball’s Cubs.

Farrell, who was trying to attract fans to the hockey team, felt that if the Curse of the Billy Goat had worked for the Cubs, the Blackhawks should have a curse of their own.

According to Farrell’s tale, after McLaughlin blamed Muldoon for the Blackhawks’ mediocre season, Muldoon shot back, “The Blackhawks will never, ever finish first in this league.”

At about the same time, Jim Coleman, a sportswriter for the Toronto Globe and Mail, embellished Farrell’s account by quoting Muldoon as saying, “Fire me, Major, and you’ll never finish first. I’ll put a curse on this team that will hoodoo it until the end of time.”

And so was born the Curse of Muldoon. Chicago actually won the Stanley Cup in 1934, 1938 and 1961, but it did not finish first in its division in any of those years. Several times in the ’60s the Blackhawks fell from the top in the dying days of the season, and the Curse of Muldoon was dusted off and retold.

The Curse of Muldoon vexed the Blackhawks and Chicagoans until 1967, when the team broke the curse. Only then did Coleman admit that he conjured up the Curse of Muldoon to break a case of writer’s block he’d had as a column deadline approached.

Although Muldoon had certified his place in Seattle hockey lore with his great Metropolitan teams, his most enduring contribution didn’t occur until four years after the Mets folded.

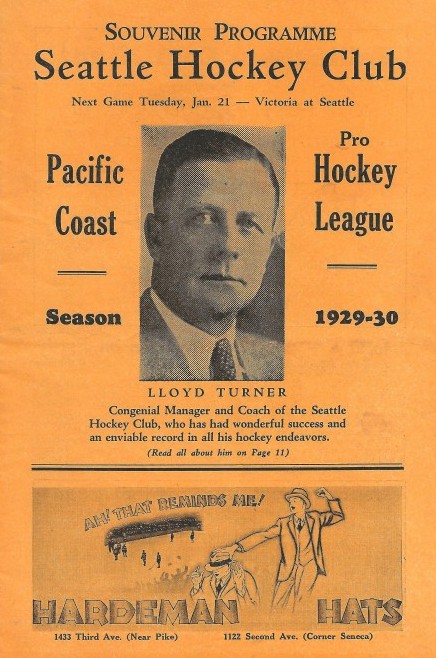

In 1928, after the city constructed a new ice palace (Civic Ice Arena), Muldoon, having returned to Seattle, rounded up several investors and established the Seattle Ice Skating and Hockey Association with the intent of forming a franchise to replace the Metropolitans, whose disbanding left Seattle sans hockey for four years.

Muldoon recruited two young real estate tycoons, Joe Gottstein and William Edris, who were then in the process of lobbying state lawmakers to legalize parimutuel wagering (see Wayback Machine: Joe Gottstein’s Racing Revival), former Seattle mayor Hugh M. Caldwell and boxing promoter Nate Druxman, as his principal investors.

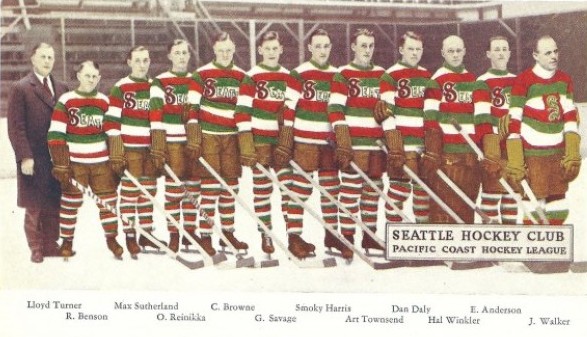

The new team they funded, the Seattle Eskimos, joined a new league, the Pacific Coast Hockey League, along with the Portland Buckaroos, Vancouver Lions and Victoria Cubs.

The Eskimos played through the 1930-31 season, at which point the PCHL folded due to dwindling attendance and rising costs.

Two years would pass before Seattle had another team, the Sea Hawks of the Northwest Hockey League. The city has had professional hockey on an almost continuous basis since: Sea Hawks (1932-41), Ironmen (1945-52), Bombers (1952-54), Americans (1955-58), Totems (1958-75), Breakers (1977-85), Thunderbirds (1985-present, now playing at ShoWare Center in Kent).

Muldoon did not live to see any post-Eskimo iteration. On March 6, 1929, Muldoon, Druxman and their aforementioned business partners were in Tacoma scouting locations for a new ice rink they hoped to build and stock with a PCHL franchise.

While driving between potential sites, Muldoon, sitting in the front seat, had a massive heart attack. His companions rushed him to Pierce County Hospital, where physicians said his death was due to acute dilation of the heart. Only at the hospital did Druxman learn from Muldoon’s physician, Dr. W.A. Glasgow, that he had treated the former hockey coach following a series of mild heart attacks.

“He was the squarest shooter I ever knew in professional sport,” said Druxman, briefly a boxer and long-time promoter who produced 11 world title fights in Seattle. ”One thing I’ll never forget: 21 years ago, Pete and I boxed on the same card at the old Seattle Athletic Club.”

After the 41-year-old Muldoon’s death, the Eskimos created an award in his honor: The Pete Muldoon Trophy. A replica went to the Seattle hockey team’s most inspirational player for many years. Sometime during World War II, the original went missing.

Totems legend Guyle Fielder back in Seattle Feb. 24

The greatest player in Seattle Totems history, Guyle Fielder, will return to the Seattle area Feb. 24.

He will autograph copies of his biography, I Just Wanted to Play Hockey / Guyle Fielder, The Unknown Superstar, by James Vantour, before the 6:05 p.m. Western Hockey League game between the Everett Silvertips and Seattle Thunderbirds at ShoWare Center in Kent.

A member of the Washington State Sports Hall of Fame, Fielder was a star in Seattle from 1953 to 1969, the last 15 seasons for the Totems.

Fielder, 5-foot-9 and 160 pounds, led the old Western Hockey League, back then a top-level minor league, in assists 12 times and in points nine times. He received 11 All-Star selections, captured six Leader Cups as the league’s Most Valuable Player, and three Fred J. Hume Cups as its Most Gentlemanly Player.

In 1956-57, playing for the Seattle Americans, Fielder was the first professional hockey player to produce 100 points in a season (122), a feat he replicated three more times. His career point total of 1,929 is still the minor league record nearly four decades after his final pro contest.

Fielder will also sign books in Portland Feb. 21 ahead of the Winterhawks’ game with Kamloops.