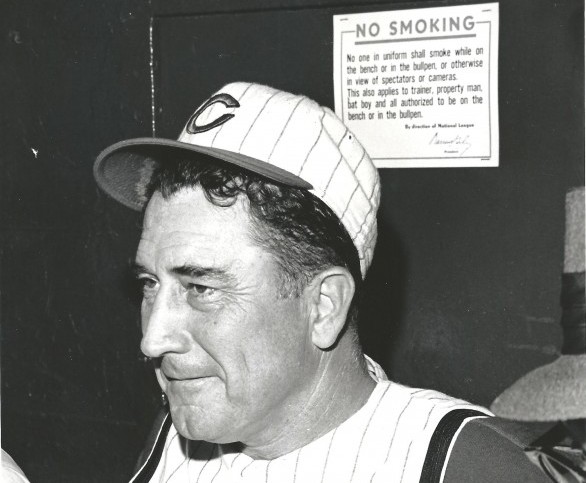

In most of the aisle-end seats at T-Mobile Park, there is an image of Fred Hutchinson, showing the Seattle native as he prepares to deliver a pitch. Those images have been there since the park opened 20 years ago. For good reason. Fred Hutchinson means a lot to Seattle. And elsewhere.

“He was a very inspiring person in many ways that touched a lot of lives,’’ said Seattle sports historian David Eskenazi, who provided the idea for the images. “He had a lasting effect on everybody that he came across. And it carries through today in the legacy of the cancer research center.’’

Born 100 years ago on Aug. 12, 1919, Hutchinson was an excellent baseball player and manager. Seattle’s prominent Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center was named for him following his death in 1964. Often referred to as Hutch, he was such a significant figure that he was ranked by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as Seattle’s No. 1 athlete of the 20th century in a December 1999 story by Dan Raley.

“Fred Hutchinson gave Seattle its first sporting icon with staying power, one recognized as a player, a manager and in death,’’ Raley told me. “His influence is seen on the cancer center, and the fact his likeness adorns rows of seats at T-Mobile Park.’’

Clay Eals, an author and journalist who is writing a book about Hutchinson, says, “Hutch was a big, big deal for Seattle.

“The ironic thing is that people know the Hutch name today mostly for something that didn’t happen in his lifetime. They know the cancer research center that was started by his brother, in his name. Not just those in Seattle but people nationally, and even worldwide, know the name Hutch more for cancer research than they do for baseball.’’

Hutchinson was so good at baseball, even as a kid, that he helped his Emerson grade school to city titles in 1931 and 1933. He attended Franklin High School, where he won 60 games and lost two.

He wasn’t just a pitcher. He also was a catcher, first baseman and outfielder. While he pitched right-handed, he batted left-handed because his older brothers had told him he would get to first base quicker. With his superb skills, he helped Franklin win several city championships.

“I was his catcher and he was the city’s most prized pitching prospect,’’ Franklin teammate and Seattle columnist Emmett Watson wrote in his 1993 book, My Life in Print. He was always a leader. At Franklin High, there was a sort of ‘Hutch cult,’ kids who liked to hang out with him.’’

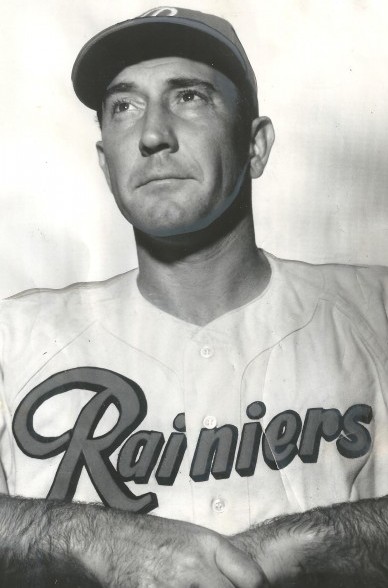

After graduating from Franklin in 1938, Hutchinson pitched for the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League at Sick’s Stadium. He was 25-7 with a 2.48 ERA with 29 complete games. And he won his 19th game on his 19th birthday, with a record attendance of 16,354 who came to see him.

Hutch didn’t just pitch professionally that season. He also batted, hitting .313 with two home runs, 13 doubles and a team-high .478 slugging percentage in 115 at-bats.

No wonder he was named the minor league player of the year by The Sporting News.

Hutchinson was signed by the Tigers and made his major league debut against the Yankees May 2, 1939, the same day Lou Gehrig ended his record 2,130-game playing streak and career.

His first game started poorly – he allowed eight runs, four hits, a home run and walked five batters while recording only two outs — but he went on to excellent seasons after spending four years with the Navy during World War II. In 1947, he went 18-10 with a 3.03 ERA for the Tigers, 17-8 in 1950 and also made the All-Star team in 1951. He finished with a record of 95-71 and a 3.73 ERA.

He also was elected to be the American League player representative from 1947-52, helping his fellow major leaguers get a higher minimum salary.

“He was a hero,’’ Eals said. “That’s the thing. That was long before the cancer research center. They just revered this guy.’’

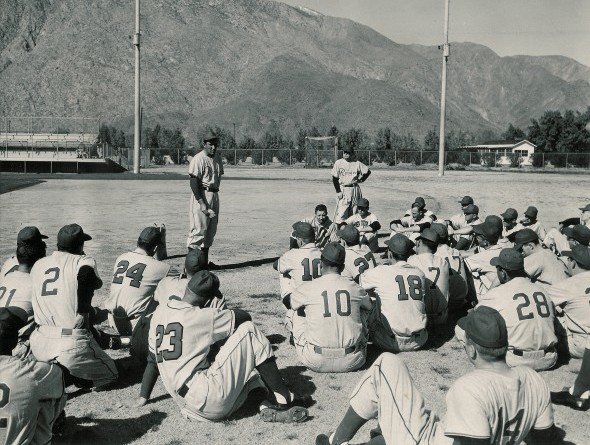

Hutchinson managed several teams, beginning with the Tigers in July 1952, less than a week after his last victory as a pitcher when he was 32. He pitched and batted sometimes as well while managing the Tigers for 2½ years.

Hutchinson went back to Seattle and managed the Rainiers for a year before returning to the majors and managing the St. Louis Cardinals for three years, where he was National League manager of the year in 1957. He returned to the Rainiers for a half season. Then he took over the Cincinnati Reds in 1959 and led the Reds to the World Series in 1961.

“He managed and led players with no artifice,’’ Eskenazi said. “His own strength and resolve, and mainly that competitive fire he had, it just inspired the players he had to give their all.’’

Among players he managed were Al Kaline, Frank Robinson, Pete Rose and Stan Musial. As Musial said in a Sports Illustrated story that was written by Watson: “Let’s put it this way: If I ever hear a player say he can’t play for Hutch, then I’ll know he can’t play for anybody.’’

Naturally, Watson also quoted his high school friend in that SI story. “I try to make a ballplayer believe in himself,’’ Hutch said, “and the only way you can do that is to give him a chance.’’

Because he reportedly smoked at least three packs of cigarettes a day, Hutchinson in December 1963 was diagnosed with lung cancer. He continued to manage the Reds until August the following season, then died three months later on Nov. 12, 1964 at 45. He was buried by his parents at the Mt. Olivet cemetery in Renton.

A year following his death, his older brother, Dr. William Hutchinson, began the creation of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Fred’s honor. Among the attendees for the 1975 dedication were baseball great Joe DiMaggio and U.S. senators Edward Kennedy and Warren Magnuson. More than 50 years later, it is one of the finest cancer research centers in the world.

The Hutch Award, started by baseball broadcaster Bob Prince, sportswriter Jim Enright and sports editor Ritter Collett, honors an MLB player who “exemplifies Hutchinson’s fighting spirit and competitive desire.’’ It has been celebrated for 25 years in Seattle with a fundraising luncheon hosted by the research center.

Honorees have included Mickey Mantle, Sandy Koufax, Carl Yastrzemski, Willie McCovey, Paul Molitor and Jamie Moyer.

“The Hutch Award wouldn’t have happened if he wasn’t such an inspirational person,’’ Eskenazi said.

Another Hutch winner is pitcher Jon Lester, a Tacoma native who was diagnosed with lymphoma in 2006 after his rookie season with the Red Sox. He was treated for the disease at the center, where he was cured. He has gone on to win 179 games since the diagnosis and received the 2008 award.

“We built the Hutch Award into a fundraising program,’’ Eals said. “It raises upwards of a million dollars a year. It’s a big deal.’’

Hall of Famer Bob Feller was at two Hutch Award festivities and also was given a tour of the Mariners ballpark when it was being built in 1999. He talked about Hutch during that tour. “He spoke of him with such great respect and affection,’’ Eskenazi said.

In a park adorned with salutes to more modern figures, including Hall of Famers Edgar Martinez and Ken Griffey Jr., as well as broadcaster Dave Niehaus, the aisle seats carry an image of long-ago greatness.

“To appreciate baseball history in Seattle, you need to appreciate Fred Hutchinson,’’ Mariners senior vice president Randy Adamack said. “He has been a legendary figure here since his days at Franklin High School through his career in the majors. His greatest honor is that his life inspired the founding of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and the outstanding work that is being done there every day.

“The Mariners are proud to be associated with the research center and to host the Hutch Award luncheon each year at T-Mobile Park.”

Which is why there is much to know about his worthiness that began a century ago.

“It wasn’t just the cause of his death,’’ Eals said. “He was the quintessential local boy made good.’’

2 Comments

What a great column, Mr. Art, especially including the Emmett Watkins (sic) parts. You are a treasure.

All credit to friend and colleague Jim Caple, whose byline was unforgivably misplaced by me early this a.m.