A civic milestone was passed Tuesday. Although to Tod Leiweke, it felt closer to passing a kidney stone.

“Fear is a powerful, powerful motivator,” he said.

He offered up all the operational anxieties swirling in his head simultaneously when the doors opened publicly for the first time to Climate Pledge Arena at Seattle Center: Public transportation, parking, ingress/egress, loading-docks, staffing, security, HVAC, audio/video, concessions, vaccination screenings.

But after the low-key test run of a benefit rock concert featuring Foo Fighters and Death Cab for Cutie, the CEO of the Seattle Kraken sounded as if the stone had passed.

Thirteen years after the NBA Sonics fled Seattle in large part because their host building was failing and taxpayers were sick of funding sports playpens, the successor to KeyArena and the Coliseum had arrived. With no cash outlay from the public.

At the moment, however, Leiweke was more concerned with the smaller picture.

“Loading a big crowd in and out was a big issue, and we did it,” Leiweke said this week by phone. “That was a super-good indicator, especially in a tough labor market, to staff the building right.

“After the concert, I looked around saw the faces of a lot of people who worked to make it happen. There were a lot of smiles. We passed a serious test.”

Not that everything was perfect.

“We had a toilet back up,” he said. “One.”

If all Leiweke had to do was make a run to Home Depot for a plunger, arena life is good.

Two more tests come this weekend: A full-tilt concert Friday by Coldplay, normally a stadium rock band that agreed to bring its elaborate sets indoors, and the home debut Saturday of the Kraken, the NHL expansion franchise whose members received their first tour of the (nearly) completed building Thursday.

They saw, as I did on a separate walk-through, many dozens of contract workers scurrying inside and out among the 1,200 full-time arena employees applying finishing touches to a project whose results can be described simply as astounding.

Square footage doubled, to 800,000. The South Atrium addition becomes a focal point at Seattle Center. Seats are comfortable, with a bit more legroom. The underground kitchen is enormous. Loading docks can handle the biggest shows. The furnishings in the suites and club seats are top tier. Concessions selections are mostly local and feature touchless transactions.

LED displays featuring vivid, animated dioramas of Northwest landscapes and seascapes adorn walls that reach as high as 40 feet.

Then there is the Green Wall.

Living plants drape from a long concourse wall and will grow “into a jungle,” according to a CPA staffer. The wall is the idea of Jeff Bezos, the retired chairman of Amazon, who signed on his company as naming-rights sponsor as long as the building represented the vision he set out in his 2019 Climate Pledge that encourages companies, rather than individuals, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a net zero in the next few years.

From Bezos’s little bookshop started in a Bellevue garage has grown wealth sufficient to help fund the world’s first net-zero arena, which means using only renewable energy resources. The arena wasn’t cheap — about $1.1 billion, a tick up from the $600 million that won the city’s bid from hated rival arena-builder AEG in 2016 — but it appears to have funded a unique gem.

Lifting his eyes up from the details, Leiweke saw the finish line.

“It’s such a wonderful thing for the community — a full-on world class arena, right in Seattle, that brings an NHL team, the biggest musical acts, and the prospects of other tenants, including the NBA,” he said. “A community like this, deserves an arena like this.”

The audacity of the idea — maintain the building’s tiny perimeter and landmark roof, dig down for more space, gut the joint, then convince the city to accept a 39-year lease and keep only a little of the revenues from public property in exchange for no up-front costs to build — was preposterous, and I said so. I was not alone.

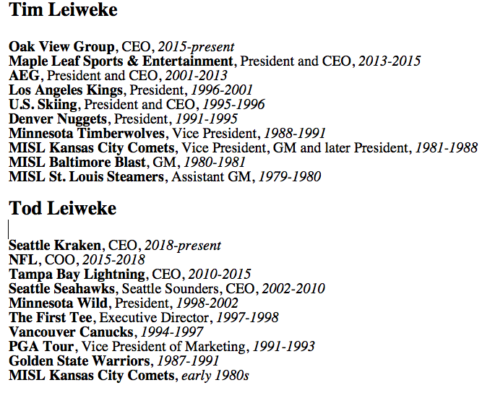

Tod’s older brother, Tim, CEO of the highly ambitious Oak View Group of Los Angeles, came up with the idea and, for awhile, was the only person on the planet who thought it would work.

“It started with the intensity of my brother,” said Tod, “and made it here through sheer force of will.”

A story in Sports Business Journal set the scene.

It’s tempting to see Seattle as the happy ending, a convergence of these two brothers with complementary skills.

“You’ve got Tim — the P.T. Barnum, the rallying the troops, the big, massive vision,” said Scott O’Neil, CEO of Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment (New Jersey Devils and Philadelphia 76ers), who is also one of Tim’s partners at Elevate Sports Ventures, a sales and marketing agency. “And then you’ve got Tod, the mastermind of sports branding and teams becoming one with their community.

“These guys are not just setting the bar at what they do, they’re in an entirely different room from everyone else.”

The happy ending has yet to be written, because the game is long. The wealth of principal owners David Bonderman and Jerry Bruckheimer is considerable, but industry sources say the group borrowed $500 million to fund construction, having also paid a $650 million franchise fee to the NHL, $80 million for a team HQ/practice facility in Northgate, and unknown millions to create a minor-league affiliate and arena in Palm Springs.

How much was cash and how much was borrowed for the little ice empire isn’t known. But everybody swirling around these Leiweke boys wants a return on investment.

They might get it.

A story on Geekwire this week quoted a survey from the jobs site Hired that said Seattle commands the second-highest average tech salary in the U.S.:

$158,000.

That’s up 4.6 percent from a year ago. Despite the pandemic.

The only average salary that’s greater is in the Bay Area ($165,000), but that’s down 0.3 percent. Seattle was ahead of New York, Los Angeles and Boston.

The Leiwekes are betting big on Seattle’s techies, many living within a few miles, spending their considerable disposable incomes in an exotic arena that can deliver the world’s premium talent to their doorsteps. So much so that the bros believe it is possible for their crews and technology to turn around three different events in a 24-hour period.

No one knows how this pending explosion of renewed activity at Seattle Center is going to impact things like daily life in the Queen Anne and Belltown neighborhoods, or the commuters using beleaguered Mercer Street, where recent upgrades are already out of date.

We’ll find out. That’s why, it is often said, we play the games.

Meanwhile, Tod Leiweke sounded as if had forgotten the pain of the stone.

“We might have the most beautiful arena in the land,” he said. “In some ways, it’s the story of the American spirit.

“That’s a cool thing to think about.”

At least it should get a fella through the time until the toilet frees up.